1980s Lviv, in five photographs by Mykhailo Frantsuzov

Many Lviv artists obtained permits for studios in the 1980s, as space became available in the basements and attics of old buildings. These were places where proletarian families or cleaning staff had lived from the 1950s to the 1970s. I myself had such a studio in a basement on Sheptytsky Street, where a large family used to live. There was only one room, it smelled of damp, and the walls were moldy. To get a decent studio in Soviet Lviv, it wasn’t enough to simply apply — you needed connections.

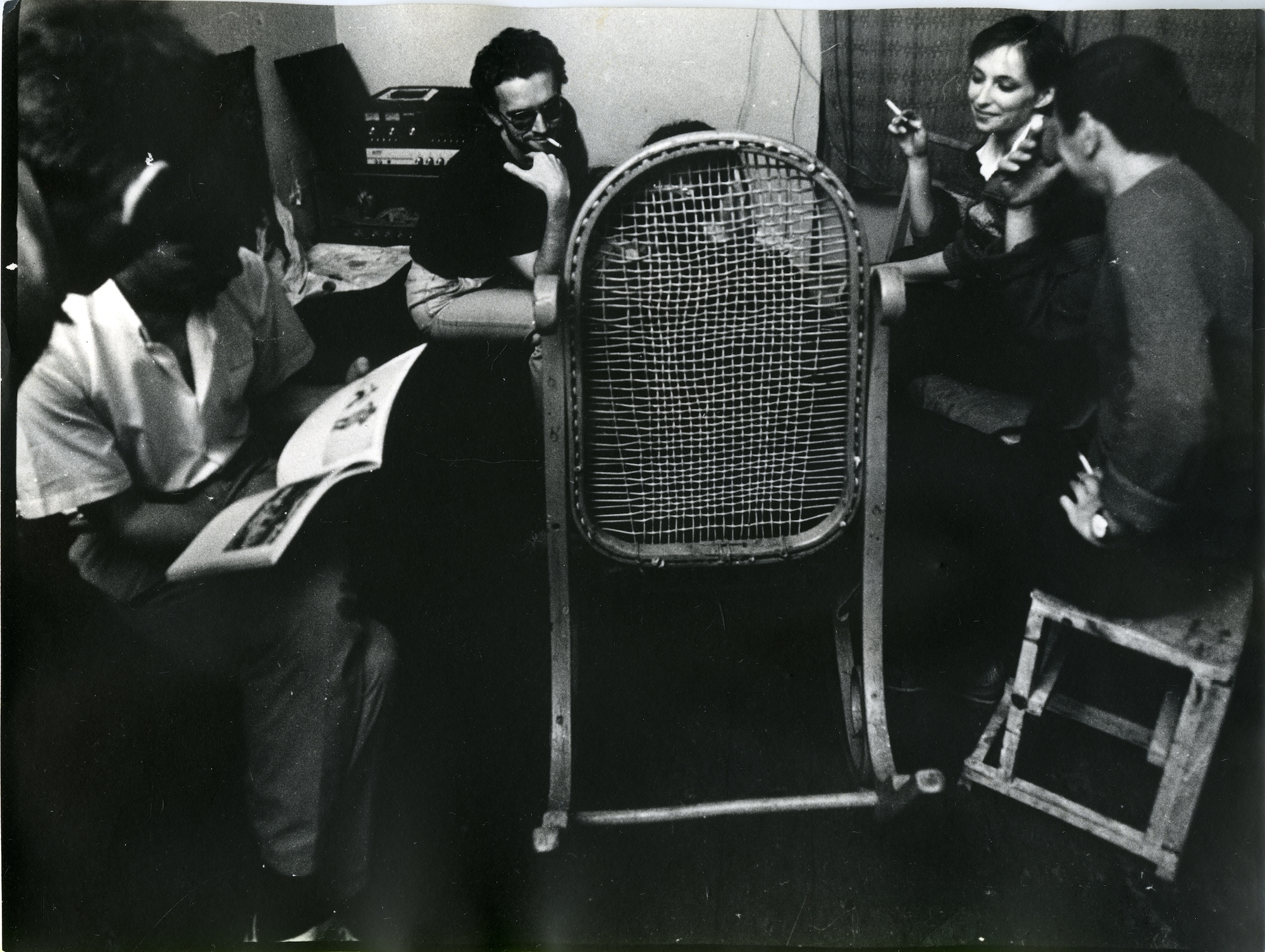

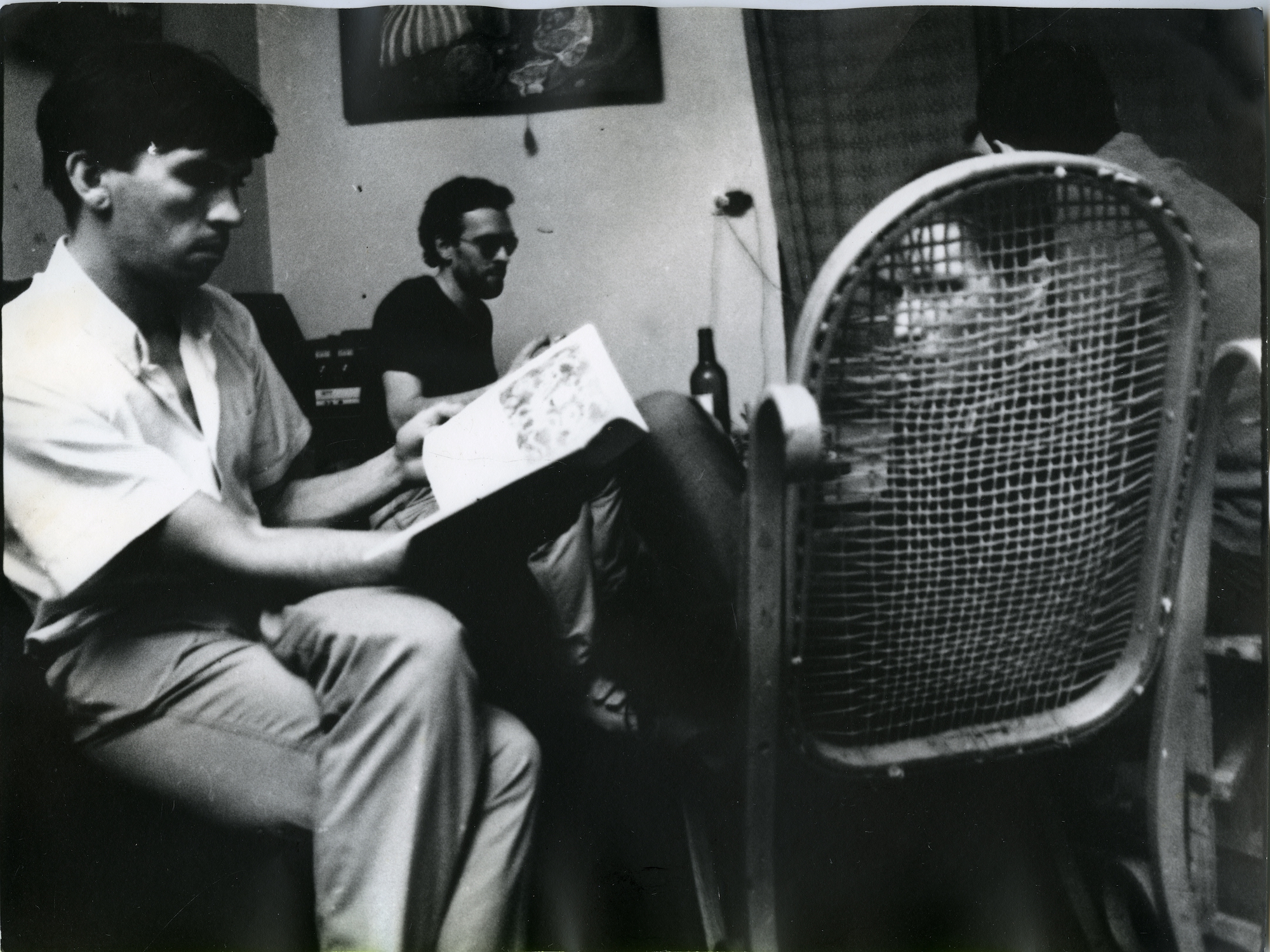

Having a studio immediately turned the ordinary Soviet artist Roman Zhuk into someone special. A studio meant freedom: it was a place where you could escape from your family, drink wine, and listen to “special” music on vinyl or cassette tapes. This is exactly what we see in Mykhailo Frantsuzov’s photographs: a table laden with bottles of wine, a stereo system, and the music connoisseur and record dealer Andriy Manilov sitting nearby. As artist Andrij Bojarov once said, any “regular Joe” who fell in with Manilov would quickly become a person of “high culture” by listening to the right kind of music. In the 1980s, Soviet people often expressed their cultural status not only through clothing (as jeans were still difficult to obtain) but also through music.

These photos were taken by Mykhailo (Misha) Frantsuzov, a prominent Lviv photographer who passed away in early December 2024. Misha belonged to the artistic circle around renowned Lviv artist and graphic designer Oleksandr Aksinin. Frantsuzov’s life was full of hardship and sadness, but he left behind an immense archive of photographs capturing Lviv’s artists, musicians, and other “strange characters” of the late Soviet period. This text focuses on one of his 1980s photo shoots in the studio of the artist Roman Zhuk.

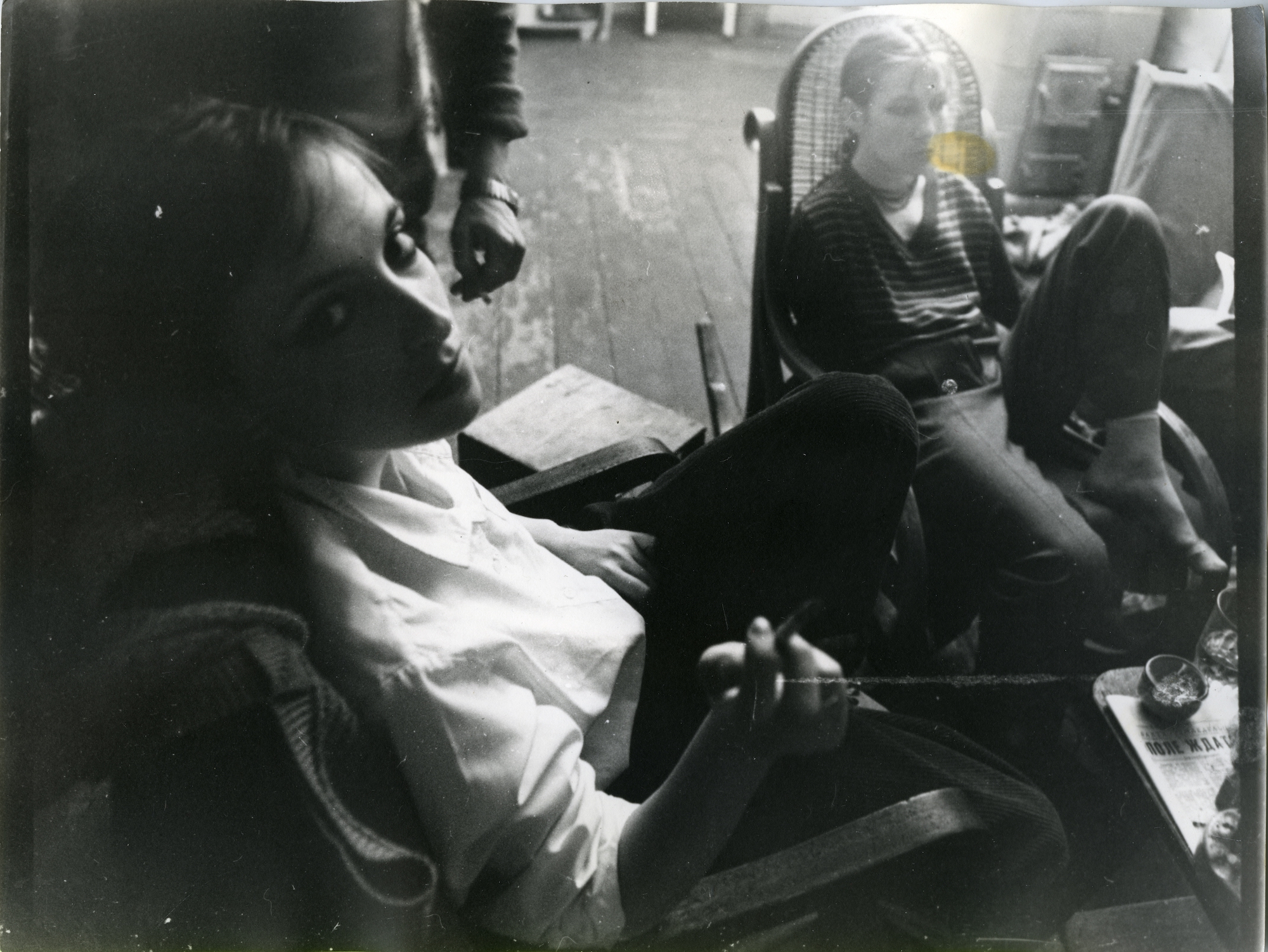

Frantsuzov loved cinema and even dreamed of becoming a cinematographer, which is why his photo series often present sequences of interconnected images that read like stills from a film. In this series, we see Iryna, Mykhailo’s ex-wife, looking confidently into the camera. She was his favorite model — striking, elegant, and often photographed with a cigarette between her fingers.

Sitting beside her is the artist Halyna Zhehulska. Known to everyone as “Dzenia”, she was “world-famous” in Lviv’s close-knit community. Dzenia was devoted to Aksinin, parties, and booze. In one image, she also looks straight at the camera; clearly, Frantsuzov photographed her often. Dzenia had distinctive features, loved smoking, and enjoyed captivating the viewer with her deep, piercing gaze. Some years ago, after Dzenia faced a serious illness, Andrij Bojarov helped the city of Lviv acquire a portion of her artistic estate. A large number of her paintings were purchased with municipal funds; the rest were snapped up by antique dealers and collectors of Aksinin’s works, many of which Dzenia had received as gifts. Ironically, her paintings are now housed in a museum called the Territory of Terror — a name that sounds almost like poetic revenge on Lviv’s unofficial art scene of the 1980s.

In another photo, we see the back of a man seated between two women. Most likely this is the artist Roman Zhuk. From this angle, we can clearly see his paintings of seashells: they were one of his favorite subjects. Zhuk’s presence is undeniable in this photo series shot in his studio on Shevchenko Street, a location that demonstrates his status as one of Lviv’s privileged artists.

The photographs also show two other men: Orest Makota and Nikolai (Kolya) Filatov. Filatov came from a Russian family that moved to Lviv after 1945, occupying one of the many homes once inhabited by Polish and Jewish families “taken away” by the war. Kolya once told me how his father returned from the front and decided to stay in Lviv, calling it “such a beautiful and empty city.”

Filatov, who dealt in jeans and illegal music, soon got bored in Lviv and left for Moscow to “conquer the capital.” There he found a job guarding a construction site for a nursery school where work had stalled. It wasn’t long before he had turned it into Moscow’s first art squat. Artists from Lviv visited often, as this was a place where they could both crash and drink. Moscow was certainly worth the trip: by the late 1980s, during perestroika, the city had become a hub of artistic experimentation and the place to see high-quality Western art.

Filatov participated in the 1989 Christie’s auction, held in the USSR during its moment of liberalization, when communists and capitalists worked together. At the auction, Elton John purchased Filatov’s work, along with that of Lviv artists Igor and Svetlana Kopystiansky, for a nontrivial sum. This story sparked the imaginations of Lviv’s young artists: it proved that it was possible to break out of the “local ghetto” of Soviet Lviv and become “world famous.” After 1989, Kolya emigrated to the United States. He later returned and became a Putinist — though perhaps a moderate one, as he now allegedly lives somewhere in Ukraine on the estate of his son-in-law, who is a notoriously wealthy Galician entrepreneur.

When Frantsuzov was still alive, I once called to ask him what the occasion was when he took those photos in Roman Zhuk’s studio. Misha told me that Filatov had just arrived from Moscow. Probably they had gotten together to drink wine, leaf through the new art catalogues he had brought, and discuss the avant-garde.

In the images, we also see the artist Orest Makota (wearing a white shirt) deeply absorbed in one of those catalogues. Often described as both a hippie and a punk, Makota loved Buddhism, wove hippie slogans into his works, and was constantly “seeking Zen.” There is another story that ties Makota, Frantsuzov, and Zhuk’s studio to the history of Ukrainian contemporary art. In the early 1990s, Makota and Frantsuzov persuaded several young women from Kolomyia to pose for a nude photo shoot. The girls believed that these “famous Lviv artists” would help them start modeling careers. Alas the young women found no modeling agencies or suitable jobs and returned home disappointed. The shoot took place in Zhuk’s studio with the understanding that if the photographs were sold, Frantsuzov would share the profits with Zhuk (who by then had emigrated to the West).

But things became complicated when Zhuk later called Misha, furiously accusing him of “shady schemes”. Apparently, some locals from Kolomyia had introduced themselves to Zhuk as “modeling agents” and demanded payment for the nude images. It turns out that Orest Makota, who spent a lot of time with the Braty Hadiukiny, had taken Frantsuzov’s photos and made a collage for the cover of the band’s album, Bulo ne liubyty (Shouldn’t Have Loved). One of the Kolomyia girls, unwittingly, became the “face” of the album, and local racketeers decided to take advantage of the situation to get money out of the musicians and artists. Frantsuzov eventually resolved the conflict with Zhuk, but he never photographed nude models in that studio again.

These five photographs from Zhuk’s studio tell many stories about late Soviet Lviv. They show us that young people had their own autonomous spaces in the city and the freedom to do what they wished there. Zhuk's studio was a place where one could spend time “outside” the Soviet world. Although the space was allocated to the artist by the socialist authorities, entirely different values prevailed within its walls. Anthropologist Marc Augé called such spaces “non-places,” sociologist Pascal Gielen described them as “semi-public spaces,” and philosopher Peter Osborne defined them as “art spaces.” Nothing extraordinary was expected to happen there; yet, paradoxically, the space itself sparked the emergence of something beyond the ordinary — something that became art. Frantsuzov’s photographs attest to this.

Translated from Ukrainian by Marta Gosovska.

Copy-edited by Larissa Babij.