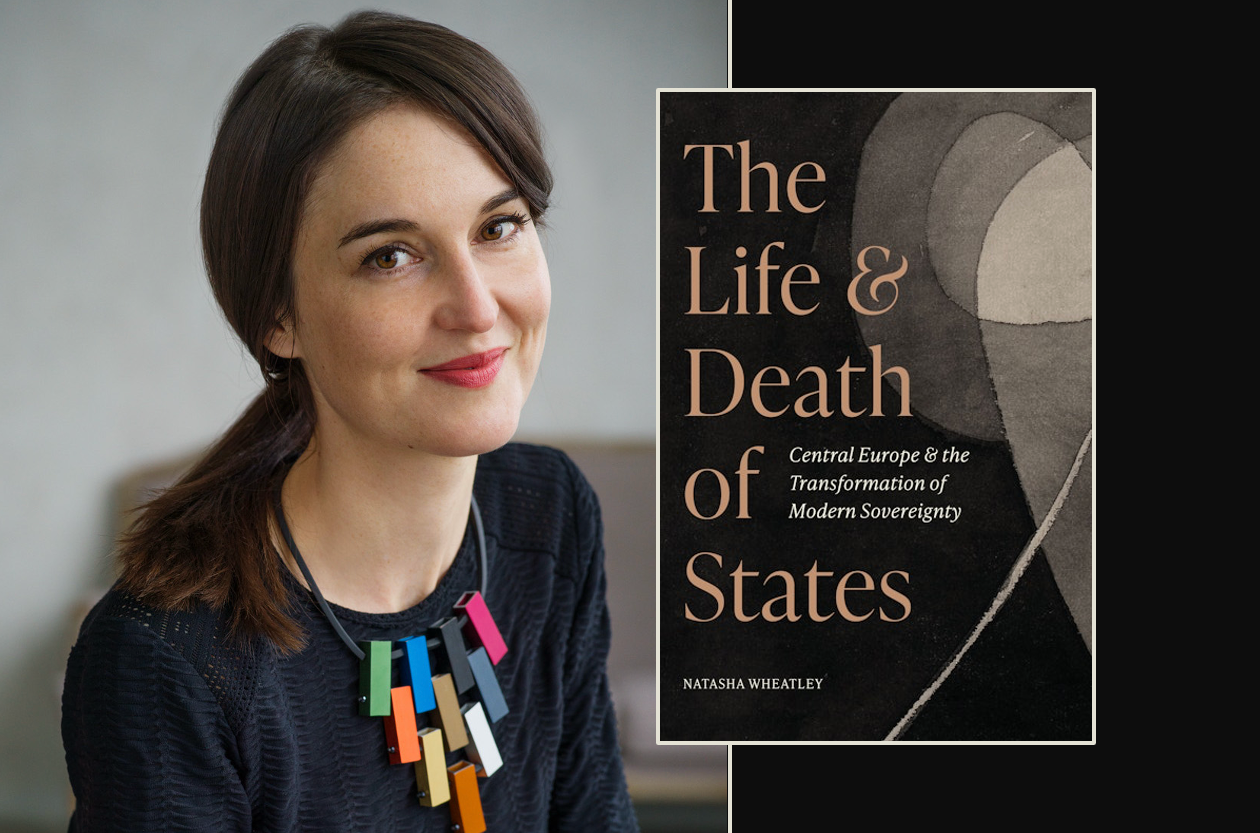

“Sovereignty exists in the realm of ideas and imagination”: an interview with historian Natasha Wheatley

Far from serving as a settled, indisputable foundation of political life, the concept of sovereignty emerges as a fragile, flexible construct, shaped by history and reactivated whenever authority, territory and legitimacy are thrown into question. We spoke with historian Natasha Wheatley, an expert on the Habsburg empire, to describe how sovereignty has been continually renegotiated under pressure – from imperial constitutional debates to post-imperial borders, international law, and contemporary war. This conversation offers a nuanced rethinking of what sovereignty is and how it has been operating throughout recent history.

Why did you choose to look into the topic of sovereignty in the Habsburg empire?

We’re always a little bit mysterious to ourselves, aren't we? When I was growing up in Australia, the single most defining public issue was the question of Indigenous land rights. When the British colonized Australia, they declared the land terra nullius – as if it belonged to no one. They didn't take seriously the idea that Indigenous people could have law or really own the land; it was a deeply colonialist and racist doctrine.

It was only in 1992 that this was legally overturned, with the Mabo decision. That court case held that Indigenous people had owned the land and that their rights had survived the act of colonization. This suggested that there might be a way in which Indigenous rights – and perhaps something like sovereignty – had persisted through 200 years of European rule.

This was a massive public debate, and there was a lot of anxiety among white Australians about what this meant. Philosophically, it was fascinating: how can rights survive through time? Could Indigenous sovereignty coexist with white settler sovereignty? Those questions struck me as not only complicated but fundamentally important because they point to the foundation of the state. In Australia’s case, our founding was essentially a crime.

At the same time, I was also obsessed with Europe. I couldn’t wait to get there. To me, it seemed like “real history” happened in Europe – the place of art, politics, and high philosophy. I spent a year in Germany after school, to learn the language, and that began a different journey.

Regarding the Habsburgs, or East Central Europe more broadly, it is the epicenter of the major transformations and events of modern history, particularly the World Wars. But more than that, the “standard” story of modern Europe is usually the British and French story. When you look at Central Europe, you see something different. It gives you a perspective that isn't beholden to the myths Europeans like to tell about themselves. It is a more fractious, complicated, and often violent history, and trying to understand that has always seemed vital to me.

When we use the word “sovereignty”, what do we actually mean?

There is no one, single thing we mean. Sovereignty is a key word of modernity, sitting at the center of public debate for several centuries. In the simplest terms, sovereignty is about the highest power – the final decision-making authority. It is the apex or the “summit” of power.

The term actually came into circulation in the 13th century in France. At the time, it was used to mean “high” things, like mountains, but also God. It eventually became attached to the power of kings, and then, over the course of modern history, to the power of the state. Because of these transformations, the concept itself has changed. When a king’s power was given by God, it was clear how it “worked”. But when you try to make the state a sovereign – a power not derived from anything else – it becomes a much trickier question.

We generally see two faces to sovereignty: internally, inside the state, it denotes the highest power within a territory. This idea evolved strongly in early modern Europe because it was thought you couldn't have competing sources of right or power in an era of religious wars. To guarantee public peace, there had to be one final authority. The external face of sovereignty, conversely, means that an entity is capable of interacting with other states as an equal. Interestingly, internally sovereignty is about there being one power, but externally it’s about there being many powers, where each is respected as sovereign.

Already, you can see the tensions. Furthermore, sovereignty in our modern world isn't something you can touch or test; it exists in the realm of ideas and imagination. It is a polemical concept, not a physical attribute, which is why it is so often a subject of intense claim-making.

Can something that is not a state possess sovereignty?

These are exactly the questions people have debated for years. In the 19th century, there was a major debate over whether only states could be part of international law. However, history is full of entities like the British East India Company – corporations that had state-like powers. They colonized, they governed, yet they weren't formally states. You can track this into the present with multinational corporations or human rights law, where individuals now have a status in international law separate from the state.

The legal theory often says statehood and sovereignty align, but the Habsburg empire is a strong example of where they didn't. It was a compound state formation containing many different lands – like Bohemia, Moravia, Hungary, Tyrol – which had gradually joined together over centuries. By the 19th century, when modern doctrines of “singular sovereignty” emerged, people asked: what does this mean for the Habsburg lands? There were so many overlapping powers. Could Bohemia be a state if the emperor held the sovereignty of the whole? That’s why Central Europe produced such rich legal thought – the answers weren't self-evident. Both the German and Habsburg empires used conglomerate forms of statehood where power was distributed in a historical federalism.

You mention the 19th century as a turning point. Was there a specific moment or debate that caused the intense intellectualization of how the Habsburg empire functioned?

We have to talk about 1848 – the year of revolutions. At the end of the previous century, the French and American revolutions had introduced ideas of “popular sovereignty” – the notion that the people, not kings, were sovereign. By 1848, these ideas were exploding in Central Europe. Liberals and nationalists were expressing deep dissatisfaction with the autocratic monarchy.

It was a dangerous moment; it wasn't clear the empire would survive. In an effort to keep things from falling apart, the emperor conceded to a constitution. This led to the Kremsier Parliament (1848–1849), an elected constituent assembly, which debated a new constitution for the empire. Even though the constitution they wrote never actually came into effect, it was a fascinating attempt to think about: what our state is and how it should be governed? Where does power come from? How should power work? For a historian, it’s a beautiful moment.

A constitution requires a description of a state. There were many possible answers. The emperor rejected the Kremsier Draft and introduced a constitution of his own, then repealed that too. They went back to non-constitutional rule in the 1850s, but when the empire became weak again in the 1860s after losing wars, they returned to the constitutional idea.

This culminated in the Ausgleich (the Compromise) of 1867, which was a very experimental settlement. We often forget how avant-garde Habsburg law was. To satisfy the Hungarians, who were a very powerful force within the empire, they created a “dual state.” It was composed of two sovereign entities: the Kingdom of Hungary on one side, and the other lands (which lacked a formal name but were colloquially called Austria) on the other. It was a creative solution to the problem of singular logic. It said: there are two sovereignties, but they are joined for foreign policy, war, and peace. They adapted modern categories to local circumstances, building a “layered” sovereignty. This is why the Habsburg empire is still seen as a rich archive for modern federal structures like the EU.

Was this solution unprecedented, or were they building on older models?

As a historian, I’ll tell you there is never anything truly new under the sun. The empire had formed through “composite monarchy,” where a monarch would acquire land (like Bohemia) and leave its laws and structures intact. The monarch simply wore many crowns.

However, the 19th century challenge was unique. In France, the revolution had wiped away overlapping jurisdictions. In Britain, the transition to a centralized state happened gradually without a written constitution. In the Habsburg case, the old legal structures were still there, but they were forced to write a constitution. They had to conceptualize that plurality for the modern age. The Ausgleich took the medieval idea of the king’s “many bodies” and translated it into a modern “shared ministry”. They ministerialized it. It was an attempt to fit a medieval federal imaginary into the organs of a modern state.

Was power truly redistributed, or was it just a rebranding of the old narrative?

Some power really was redistributed. But it was also a consolidation. For example, Bohemia “lost out” because the Czechs became part of a larger Austrian entity rather than having their own distinct trialist structure (a three-part empire). Hungary got fulsome autonomy, but other lands lost space, even if they still had their own jurisdictional space within their half of the empire. It’s a limitation of the approach. I’m interested in the concepts, but the concrete power shifts were often quite stark.

What is the relationship between sovereignty and independence, and when did they start to be lumped together?

Over the 20th century, sovereignty really became synonymous with self-determination, with the bid for autonomy. It speaks to deep-seated human needs for control over one’s identity. Sovereignty also carries the legacy of the “glory” of kings; it’s something that can be insulted or injured.

However, the world we live in now makes full autonomy a fantasy. The nature of the global economy means no state has full control. Some historians argue that sovereignty was “given” to everyone in the mid-20th century precisely because it meant less than it used to. For example, Britain might have granted Iraq independence but kept control over its oil. What does sovereignty mean if you don’t control your resources? The nation state has limited room because a lot of power is distributed at international and global levels.

In Ukraine, the idea that nation states are losing sovereignty is often seen as a dangerous narrative, one used by Russia to undermine the state. On one hand, we can theorize about nation states lacking power, but on the other, it is a very tangible thing right here, in Ukraine.

Absolutely. Ukraine and this war against it are a jolt to these debates because they represent a return to an older, very literal logic. We are seeing people fight over meters of territory, laying their lives to defend a territory. It is a reminder that states are still in space and that physical space matters immensely.

Even if power is diffuse, the nation state remains the only forum we have for democracy. All our democracies are imperfect, but the nation state is the only place where we can involve people in government. Until we come up with a better way to organize our engagement with power, we have to insist on the importance of the nation state. Otherwise, we are giving power over to forces that remain beyond human control.

We’ve been talking about the lives of states. Let’s talk about the death of one, about 1919 and the collapse of the Habsburg empire. What happened, intellectually, with regard to the concept of sovereignty?

The end of World War I remade Europe. The Habsburg, Russian, Ottoman, and German empires all collapsed. In the Habsburg lands, the multinational empire was replaced by a string of new nation states. Nationalists at the time said the empire was an anachronism, that it was natural for it to give way to these new states.

But historians now point out that the Habsburg empire was still reasonably functional until the very end. It was quite progressive in certain ways; it had a multilingual policy where the state provided schooling in all languages and the army was a multilingual institution. You could speak to the state in any language you wanted – something hard to imagine in many parts of the world today.

The new “nation states” remained extremely multi-ethnic. Populations lived in an intermingled way. This created an intense debate in the interwar years about the “normative foundation” of sovereignty. Hitler used the presence of a German majority in the western parts of Czechoslovakia (Sudetenland) as an excuse for annexation. It was only after the horrific ethnic cleansing and genocide of World War II that we got the more “straightforward” nation state model of Europe. The struggle to align people and boundaries was the big, often violent story of the 20th century in that part of the world.

How were those borders actually decided in 1919?

It was much more chaotic and amateur than we can imagine. I’ve been through the files of the Paris Peace Conference committee, and you see them scribbling lines on maps. A lot of it came down to procedure and contingency. For example, the Czechs were able to present themselves as being on the side of the Allies, while the Hungarians were seen as the losers of the war. Hungary ended up being whatever was ‘left over’ once the other borders were determined.

There were a lot of contradictions. In the Czech case, they used the “national principle” to argue for the inclusion of Slovaks, but then used the “historic boundary” principle to claim the Sudetenland (where a German majority lived). They used different principles in different directions to draw the boundaries. It was a process of learning by doing – and improvising.

One of the core statements in your book is that “post-imperial is not post-colonial.” Can you expand on that?

I want to think about the collapse of these European empires alongside the broader story of the end of empire in the rest of the world, but without pretending the cases are identical. In the Habsburg empire, everyone had citizenship. There wasn't the same racialized revolution of power as in many overseas colonies.

However, the “laws of succession” are a fascinating commonality. When a state ends, who picks up the obligations? Do rights die with the state? This became a huge question for postcolonial states in Africa and Asia in the 1950s and 1960s, but the question returned to Europe at the end of the Cold War. With the collapse of Yugoslavia and the USSR, we had to ask: can the Russian Federation inherit the legal personality of the old USSR? Can it keep the UN Security Council seat? History keeps returning to these questions of “refounding” and whether there is continuity or death for a state.

As I mentioned before, in 1919, the Czechs and Hungarians both claimed to be the legal continuers of old state traditions (the kingdoms of Bohemia and Hungary). They said these rights had been preserved through the empire and were now being reclaimed. The only ones who said they didn't continue anything were the Austrians. They wanted to be seen as a brand-new ‘rump state’ so they wouldn't be saddled with the empire’s war debts. It shows that these aren't statements of fact; they are arguments over how power works, mediated through legal categories.

But also, we rely on our belief that the law is something objective, when it is also a product of imagination and agreements, which, as we know perfectly, can be violated without major repercussions.

Exactly. Law is a product of our imagination. It's something that we think up, but it often does have very real-world consequences. People use law as polemical creatures, to try and change the world, not just to describe it.

Are there lessons we can take from the Habsburg past into our current geopolitical climate?

I often shy away from “clear lessons”, but history can illuminate our thinking and make it more subtle and open-ended. We can easily forget how different the world used to be and how different it could be. History helps ‘loosen our heads’ so we don't see our present as inevitable.

The Habsburg past reminds us that we can think flexibly about statehood. We often see the empire as a failure, but it survived for hundreds of years. It managed pluralism and difference through accommodation. One creative idea from the Austro-Marxists was a national curia, a non-territorial national autonomy. They recognized that nations live in an intermingled way, so you couldn't just draw a circle on a map and give a nation autonomy without displacing people. Instead, they suggested arranging national membership like church membership. Wherever you lived, you could pay into a national fund that would run your schools and cultural programs. It was a cultural set of rights rather than a territorial jurisdiction. It’s a creative way to think about power that doesn't rely solely on geography.

Historians focus so much on why the Habsburg empire collapsed. Why did it collapse?

For a long time, the dominant theory was that nationalism brought it down – that it was a “prison house of nations” that naturally gave way to liberty. But historians today see it differently. The pressures of World War I were the real cause. Over four years of total war, the state stopped being able to provide basic social services – food, welfare, and safety. When the central state failed to uphold its part of the social contract, legitimacy shifted to national activist groups who were already providing soup kitchens and schooling. War puts extreme pressure on states. The Habsburg collapse was a multi-causal event driven by the state's inability to care for its people under pressure.

Does your current work continue to explore the notion of sovereignty?

Yes. I am working on a project called Laws of Water, Air, Earth, and Fire: Sovereignty Among the Elements. I’m looking at how new technologies in the interwar years – airplanes, submarines, radio – put massive pressure on the territoriality of the state. When an airplane can fly over a border and drop a bomb, what does a border mean? It was a crisis for late 19th-century thinking, which was obsessed with control over territory. It created a territorially disembodied violence where there was no relationship between the perpetrator and the victim.

This also resonates today with the Anthropocene. Our environment doesn't respect state boundaries, and climate change doesn't care whose jurisdiction is on this or that territory. Nature just storms over boundaries. What does it mean for political power and control?

Coming back to the war in Ukraine, it makes borders feel very physical: from a train, you can see 500 meters of land. The missile can fall on one side, but on the other side, that’s highly unlikely.

This is the reason why the war in Ukraine is a jolt to the European public sphere – because it is so literal. As you say, when you cross the border, you physically feel the difference between a place where a bomb might fall and where it won't. It’s a matter of life and death. We had grown complacent, thinking we lived in a “post-physical” Europe of virtuality and open borders. The re-territorialization of politics shows that it was naive to think the era of physical space had passed.

Did the European Union draw some inspiration from the Habsburg empire? Is the EU an empire in any way?

It’s a fascinating question because it's used so polemically. Viktor Orbán loves calling the EU an empire to insult it, while some liberals in Brussels use the Habsburg empire as a positive model. But “the empire” isn't the same pejorative term for everyone; it depends on which empire we mean.

The EU and the Habsburg empire are both solutions to the “problem of small states.” In the 19th century, people realized that to compete with powers like the US, you needed landmass, markets, and resources. Alliances also produce autonomy. As František Palacký said in 1848, if the Habsburg empire didn't exist, we'd have to invent it, because small nations need to be part of a larger defensive structure to survive. We are always returning to this question: how do we arrange power between the large and the small?