Grief: the story behind an iconic World War II photograph

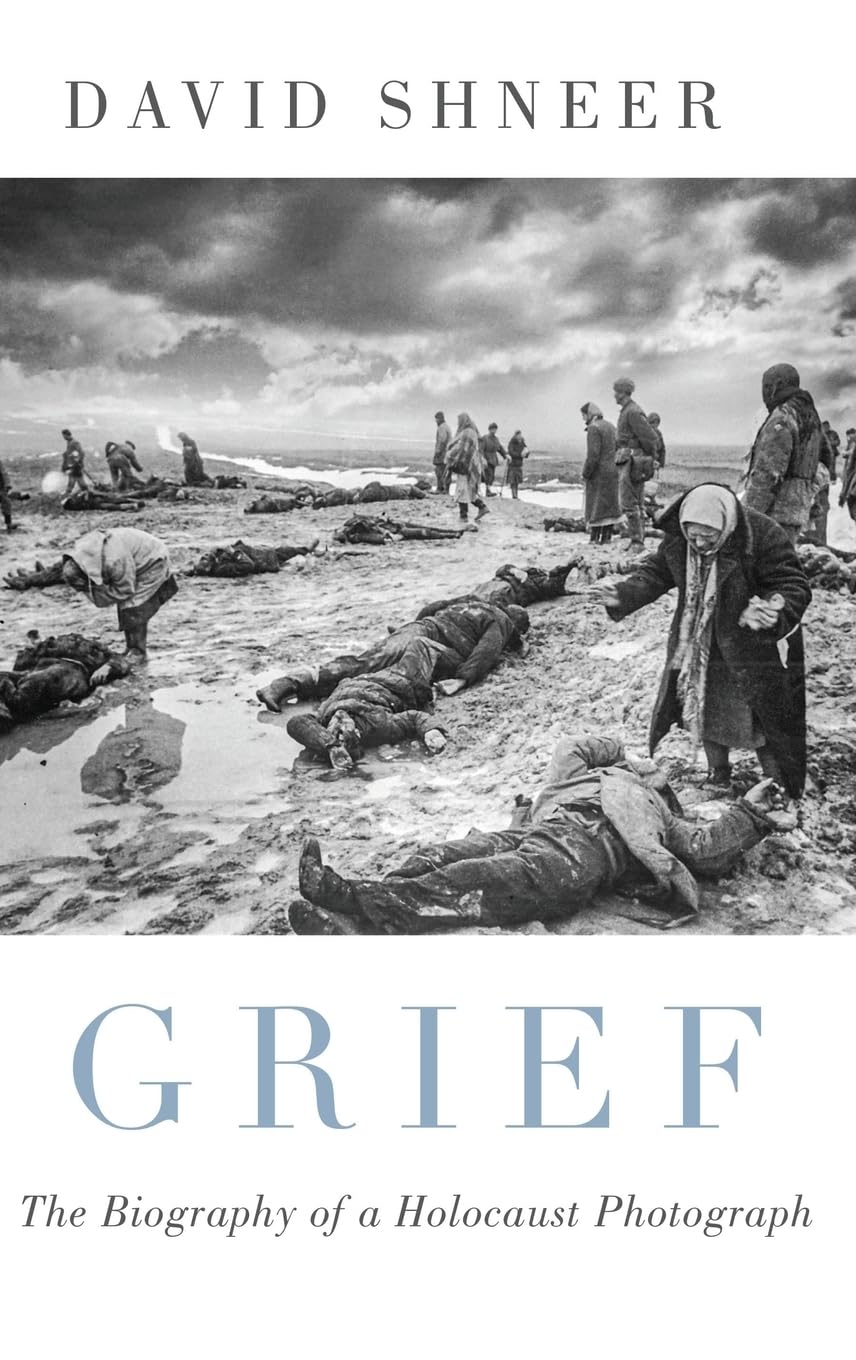

American professor David Shneer's 2020 book “Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph” tells the story of World War II frontline Soviet photographer Dmitry Baltermants. It focuses specifically on one exceptional photograph he made, titled “Grief.” Through this world-renowned picture, Shneer highlights deeper processes and explores the controversial figure of Baltermants himself, who was both lauded for his talent and criticized for propaganda and image manipulation. How much can be said by, and through, a single photograph?

David Shneer (1972–2020) was a renowned researcher who, in his earlier book Through Jewish Soviet Eyes: Photography, War, and the Holocaust, was among the first to draw special attention to Soviet frontline photographers who accompanied the troops during World War II as they de-occupied the country from the Nazis. It was, in fact, through their photographs — selected, framed, retouched, published, and reproduced, often accompanied by captions and articles — that the world came to learn about the Nazi crimes committed on Soviet territories.

The book Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph is dedicated to one of these frontline photographers, Dmitri Baltermants (1912–1990), and, in particular, to one exceptional photograph by him, entitled Grief.

Shneer recounts his search, marked by fortuitous encounters and strokes of research luck, which led him to discover previously unknown versions of the same photograph and reconstruct the work that had been done on it. His original idea — to recreate the story of the central figure in the photo, a grieving woman named Ivanova standing over the body of her husband at the site in Kerch where the Nazis had executed Jews, other civilians, and partisans — proved unrealizable. After 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and made a trip to Kerch impossible, Shneer turned his focus to Baltermants and his photographs, studying them in depth. He wrote a book about how visual images of war are created and circulated — between photographer and audiences — with the involvement of media, unions, curators, art dealers, propagandists, and promoters. The book spans the entire 20th century, tracing the “biography of a photograph” not only in relation to its creator’s life, but also in the years after his death.

Dmitri Baltermants was shaped as a photographer in Moscow, then the heart of Soviet avant-garde and, later, Socialist realist photography. His mother’s Jewish and Warsaw background proved advantageous: multilingual, she secured a position at the Izvestia newspaper and, in 1926, helped her son obtain a job there as a type designer.

It was at Izvestia that Dmitri was introduced to photography, working as an assistant to the already well-known photographer Georgy Zelma. Even at that early stage, he applied constructivist techniques — such as montage — to the Socialist realist glorification of Stalin and Soviet achievements. The newspaper’s editorial board also helped him gain admission to the Faculty of Labor at Moscow University — an uncommon path for photographers at the time, most of whom lacked a university education. Baltermants graduated in 1939.

In 1939, Dmitri Baltermants’s skills became geopolitically significant for the first time: the Soviet Union was seeking to represent itself in the newly annexed territories of eastern Poland, and Baltermants was tasked to photograph the city of Lviv. In describing these events, Schneer consistently transliterates the names of Soviet cities using Russian forms — Lvov, Kiev, and so on — and presents the situation primarily from the Soviet perspective, which claimed to be liberating “Belarusians, Ukrainians, and others who were oppressed by brutal regimes, especially in Poland, which had controlled the lands of the former tsarist empire before the First World War” (however, it is worth noting that eastern Galicia and Lviv were never part of the Russian empire, and thus were not the “old-new lands” Shneer refers to). Commenting on how the Sovietization of western Ukraine was reflected in newspaper photography, Shneer observes: “While the pages of Izvestia and Pravda were filled with smiling faces of western Ukrainians greeting their Soviet Russian brothers, there were no images of deported Poles, Jews, or others sent to Soviet Siberia.” This kind of portrayal points to an essentialist approach to ethnic categories — an approach that not only oversimplifies the historical situation but also distorts it. It overlooks both the mass deportations that included Ukrainians and the initial intentions of the Soviet government in 1939–1941 to preserve the multiethnic character of society in the annexed territories.

Throughout the book, one also finds a recurring terminological conflation of Russia and the Soviet Union — a tendency typical of older generations of American Sovietologists. For example, Shneer writes: “In southern Russia, by the late fall of that year, as the days grew shorter and the ground hardened, almost all of Ukraine was in German hands.”

In the very first chapter, Shneer also addresses — drawing on existing research — the situation in Kerch in 1941–1942, including the central event captured in the photograph Grief: the mass shooting of Jews, other civilians, and individuals identified as partisans in early December 1941, carried out in anti-tank ditches in Baherove, on the outskirts of the city. Throughout the book, the author consistently refers to Crimean Tatars and occasionally Ukrainians as collaborators in the Holocaust in Crimea but never mentions local Russians or Germans in this context. However, studies based on postwar court proceedings show a more complex picture: the proportion of ethnic Russians and Ukrainians among those convicted of collaboration was slightly lower than their respective shares in the population, whereas the proportion of ethnic Germans convicted was significantly higher than their demographic presence. Moreover, there was a notable difference in roles: Germans often held administrative and police positions; Crimean Tatars were more frequently involved with the Einsatzgruppen; and Ukrainians were often convicted for so-called “nationalist” activities.

Baltermants took the photograph Grief, the central subject of the book, in 1942, when he arrived in Kerch with Soviet paratroopers. There, he witnessed the exhumations at Baherove. Shneer writes about how the events of the Nazi occupation of Kerch were perceived and represented following the arrival of “ours” — as the local population referred to the Soviet army — in early 1942, after the Nazis retreated in the wake of an unexpectedly successful Soviet offensive.

The Commission for the Establishment and Investigation of the Atrocities of the German Fascist Invaders, which operated from 1942 to 1945, laid the foundation for how such events were covered in Soviet newspapers. Notably, the commission’s very language began to obscure or downplay the specifically Jewish identity of the victims, instead framing their suffering as part of the broader sacrifice of the entire “Soviet people.” Baherove became the first — and precedent-setting — case of a mass shooting to be publicly exposed by the Soviets. Although Soviet audiences were already familiar with visual images of mass violence through Nazi trophy photographs published in the press since the summer of 1941, the scale of the atrocity uncovered at Baherove proved particularly shocking.

A few photographers, including Yevgeny Khaldei, documented what they witnessed and published their images in the Soviet press. However, only one photograph became truly iconic: Dmitri Baltermants’s Grief, first published in March 1942 as part of a photo essay in the Ogoniok magazine. Shneer examines in detail the distinctive qualities of this image in comparison with other photographs by Baltermants and his contemporaries, analyzing its composition, artistic features, photographer’s perspective, and differences in content.

Grief conveyed a mass tragedy through the singular figure of a woman named Ivanova, who is shown in despair over the body of her murdered husband. This approach echoed a long-standing global tradition of “battle scenes” in painting and later photography, where mourning and grief follow combat. In contrast, other photographs tended to present more generalized images of the dead or included captions with distinctly Jewish surnames and/or depictions of women and children as victims — elements that directly evoked the genocidal nature of the Nazi campaign (but which clashed with the official Soviet propaganda line). What set Grief apart was its visual and emotional reference to classical art — both the pathos formula and the pietà — which gave the image a powerful resonance in an international context. Shneer undertook a remarkable effort to locate and meticulously compare early publications of the photograph, work that helped illuminate how Grief laid the groundwork for the Soviet visual and narrative discourse surrounding Nazi occupation and war crimes.

Throughout the remaining war years, Baltermants was a rising star, with his frontline photographs regularly appearing on the front pages of Izvestia, often on a weekly basis. His work also reached international audiences: British and American correspondents in Moscow who were sympathetic to the Soviet Union — then an ally — sent images by Soviet photographers to their respective publications. However, this very international exposure played a critical role in Baltermants’s downfall. In one photograph published in a British newspaper, he mistakenly identified a Nazi tank as a Soviet one — an error that was politically unacceptable. As a result, he was dismissed from Izvestia, stripped of his military rank, and sent to a penal battalion in the summer of 1942. Baltermants would later interpret this as a Stalinist reprisal, despite his otherwise successful career and his prominent role in shaping the visual language of the Socialist realist cult. His serious injury during service functioned, in a sense, as an “atonement” for his mistake. After being released from the hospital in 1943, he returned to work as a photographer for the newspaper Na Razgrom Vraga (To the Defeat of the Enemy), and in 1945 he joined Ogoniok as a staff photographer.

In the reconquered territories, photographers documented the aftermath of countless Nazi crimes while working for the Extraordinary State Commission. The Nuremberg trial drew, among other sources, on photographs from Kerch — though these images were not used as evidence to convict specific individuals. In the decades that followed, Baltermants became one of the most prominent photographers of the Soviet establishment, making portraits of Soviet leaders, iconic images of domestic policy shifts, international events, and of leaders of countries aligned with or gravitating toward the USSR.

The 1960s Thaw period was marked by a revival of the Soviet Photo magazine, the growth of a grassroots culture of amateur photography, the admission of foreign journalists, and an increase in international travel and “people’s diplomacy.” These developments coincided with the busy activities of the All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (VOKS), which established a dedicated photography department in 1958, headed by Baltermants. This department was frequently visited by international delegations, as was the Central House of Artists in Moscow.

Photography, becoming an increasingly popular and accessible medium, was relied upon to craft a new global image of the USSR — as an open and attractive country, a center for students and immigrants from Asia, Africa, and Latin America, and a pillar of “people’s democracies.” The focus on the “common man” replaced the earlier cult of the leader and was reflected in photography that increasingly highlighted everyday life.

This shift was also a response to similar trends in Western photography: for example, the 1959 American exhibition shown in the USSR included The Family of Man, an ambitious project by MoMA’s director of photography Edward Steichen which showcased photographs of everyday life from around the world. Soviet traveling exhibitions adopted a similar model, emphasizing everyday life while simultaneously reminding the world of the unique Soviet suffering during World War II and the “Great Victory” that underpinned the USSR’s moral legitimacy. This “soft power” of culture and imagery of the past operated alongside “hard power” — as exemplified by the 1957 exhibition in Budapest, held shortly after the brutal suppression of the Hungarian uprising. In that context, cultural influence was intended to promote reconciliation and stability.

Baltermants’s photographs gained greater international prominence in the 1960s and 1970s, a period marked by increased attention to the memory of World War II. For instance, an international exhibition in 1968, curated by the Italian photographer Caio Garrubba, presented a stark and critical portrayal of humanity. Photographs of atrocities from the eastern front — including Grief — fit seamlessly into this narrative. Critics interpreted Baltermants’s images as expressing a universal grief: a woman mourning a dead man, unburdened by specific historical details, making them ideal for cultural diplomacy and broad audiences. For this exhibition, Baltermants produced his own version of the iconic image of Ivanova, which later became well-known. Taking a controversial step, he superimposed two different shots, adding a dramatic cloudy sky to the scene of the woman’s grief and retouching the image to correct what he cited as purely technical flaws in the original negative. This alteration gave the photograph a new function — not just documentary evidence but also an artistic statement. While professionals noticed this manipulation and often criticized it as deceptive, Shneer frames it within an “alternative” understanding of documentary in Socialist realism: documentary work is not merely the recording of facts but also the conveyance of their deeper class, social, and political significance. Shneer persuasively traces the continuity of this approach from the avant-garde through Socialist realism in the 1930s and into subsequent decades. Indeed, Baltermants frequently employed collage and combination techniques, as seen in his depiction of factory workers’ grief over Stalin’s death and in his Kerch Grief.

Shneer provides a detailed account of how Grief gained international popularity, tracing its rise through personal connections, support from national and international institutions, and the democratization and commercialization of photography. Baltermants’s growing position within the Soviet establishment increasingly granted him access to international contacts. After organizing an exhibition of the British photographer Ida Kar in Moscow, Baltermants was invited to London for a solo exhibition in 1964 — an opportunity made possible not only by the British Communist party but also by individual professionals and promoters, many of whom came from the Russian empire and the USSR and possessed the necessary sympathies and expertise. The exhibition’s five leading photographs were wartime images, accompanied by a catalog text written by Konstantin Simonov, a writer with extensive experience as a war publicist. That same year, the major exhibition What Is Man? by Karl Pawek and Heinrich Böll showcased Grief in Hamburg and then toured many European cities. The photograph won the Audience Award and a prize, cementing its status as an iconic image of Soviet cultural diplomacy. In 1965, Baltermants became the photo editor of Ogoniok, and it was also the year when photographs from the Kerch moat were published in the USSR for the first time.

Shneer traces the evolving understanding of photography’s value — from a purely documentary medium to a tool of diplomacy, then an artistic object, and finally a commodity. He places the history of Soviet photography within the broader development of the global infrastructure of cultural exchange and the emerging photographic market. Grief became part of this process through its presentation at key institutions in the United States, including the Graphic Masters Association (GMA) in 1965, where it featured in an exhibition of eleven photographers from around the world. Grief was the only photograph from a Socialist country and the sole non-contemporary work, symbolizing the USSR’s uniqueness by highlighting its particular suffering during the World War II. The photograph was also exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1967. During the 1970s, Baltermants held solo exhibitions in many European cities, with Grief almost invariably appearing on the covers of the exhibition catalogs. It was only after the photograph achieved worldwide recognition that all the images from this series were made publicly available in the USSR.

David Shneer describes how international photography experts began recognizing the potential value of Soviet photography and negotiated the worth of certain works, as the professions of art dealers and auction houses gained prominence. During the 1980s Perestroika period, Baltermants’s daughter, Tatiana — a translator —traveled abroad with her father and came to realize the commercial potential of his photographs. Around this time, many collectors and dealers started viewing Grief through the lens of the increasingly fashionable Soviet avant-garde. The unexpected death of Dmitri Baltermants in 1990 left Tatiana with the responsibility of advancing his legacy. She traveled to the opening of a significant exhibition in Los Angeles that same year, after which Grief entered the international art market.

The sixth chapter of the book, titled How Woe Became a Commodity, is devoted to this very topic. Shneer analyzes the obituaries of Baltermants, where he is often compared to Robert Capa, and where Grief is frequently misinterpreted as a war photograph. The exhibition in Los Angeles was a great success. As Shneer notes somewhat ironically, “it was probably the death of the artist and the death of the Soviet Union that allowed viewers to appreciate the aesthetic qualities” of the work outside the Cold War context and its associated political interpretations. Commentators began to link Dmitri Baltermants, Yevgeny Khaldei, and Alexander Rodchenko within the broader history of the “Russian avant-garde.” Rodchenko, romanticized as a victim of repression and a visionary genius seeking creative freedom — often without acknowledging his work under Stalinism and during the war — became a central figure in discussions of Soviet photography. Consequently, constructivism and modernism gained renewed popularity. The successful auction sales of Baltermants’s works — both individual pieces and portfolios, which included wartime photographs alongside iconic images of Soviet places, events, and prominent figures — signaled the transition of Soviet photography into the realm of cultural heritage. An attempt to codify this heritage can be seen in Baltermants’s photo book Faces of a Nation: The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union, 1917–1991, in which his daughter Tatiana wrote the foreword. Art institutions began actively acquiring or accepting Baltermants’s works as gifts, and by the mid-1990s, all leading western art institutions had included them in their permanent collections.

The photographer’s material legacy — his negatives — has an even more complicated history. In the 1990s, Baltermants’s daughter sold them to a U.S. collector. However, as Putin’s promotion of victory in the “Great Patriotic War” as a cornerstone of Russian identity gained momentum, the negatives were repurchased in 2010 by Sobranie.PhotoEffect, the world’s largest investment fund specializing in photography, which began acquiring collections by Russian and other photographers worldwide for staggering sums. Works of art were increasingly seen as status symbols and investment assets. By 2012, Sobranie was liquidated, and its entire collection was auctioned off. The fate of Baltermants’ archive remains unknown; according to Shneer, it was most likely acquired by Gazprom.

As the study of photographic evidence of the Holocaust developed into a distinct discipline, the interpretation of the photograph Grief shifted from being seen as a “battle scene” to a powerful representation of the genocide of the Jewish people. This shift involved not only the illustrative use of photographs but also a deeper focus on the history of individual images and their social function, especially in the postwar period. A significant milestone in this process was the 2012 exhibition Through Jewish Soviet Eyes, co-curated by David Shneer and the director of the University of Colorado Museum of Art. This exhibition critically examined the creation and circulation of photographs by Yevgeny Khaldei, Georgy Zelma, and Dmitri Baltermants. Five years later, the Museum Association of British Columbia in Canada organized an exhibition of Baltermants’s photographs, interpreting them as “scenes” of Soviet reality that both reveal and obscure aspects of the past.

Shneer pays particular attention to the archiving of Grief at Yad Vashem. Initially, the museum tended to avoid retouched photographs, but over time, a more critical understanding of the “man-made” nature of photography led to their inclusion — although with careful descriptions outlining the alterations made. Contrary to something Shneer describes as “a tendency among Holocaust museums of interpreting photographs within a framework of Jewish exceptionalism and focusing solely on the genocidal murder of Jews,” he argues that Grief is “the perfect photograph of the Holocaust” because it depicts both Jewish and non-Jewish victims. The image broadens the concept of the Holocaust, conveying the complexity of the events and the multiplicity of violent experiences in the occupied eastern territories.

The second part of the final chapter examines Jewish commemoration of the Holocaust in Kerch through two dimensions of memory: the global Holocaust discourse and the practices of the local Jewish community. Unable to visit the site of the shootings in person, David Shneer draws on a wide range of sources, including news reports of commemoration ceremonies, captions from thematic school drawings, press interviews, and research interviews — among them those conducted by Mykhaylo Tyaglyy for the Shoah Foundation, founded by Steven Spielberg, and Father Patrick Desbois of Yahad-In Unum.

The author concludes the book with the hope that, one day, the Jewish community of Kerch might choose to incorporate the photograph Grief into their annual commemorative events. Such a gesture would highlight a local way of remembering the Holocaust — one that “transcends narrow ethnic nationalism” and situates Jewish suffering within the broader context of all victims. While this emphasis is certainly interesting, it must be clearly distinguished from the Soviet culture of memory, which effectively appropriated Jewish suffering to symbolize the sacrifice of the entire “Soviet people.”

***

Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph exemplifies how the biographical genre can illuminate broad, even global processes, while importantly avoiding the usual focus on “outstanding personality” or “creative genius.” Instead, it centers on a figure whose work was described by contemporaries not only as talented photography but also as propaganda, clichéd productions, and manipulated images. Baltermants exists beyond the simplistic categories of genius or villain; rather, he was a bureaucrat and a career professional who adapted to each era and created its visual “chronicle.”

It’s important that Shneer identified the numerous mechanisms — both institutional and private — that shaped the international cultural diplomacy of the USSR. Over time, this diplomacy increasingly relied on the memory and legacy of World War II and became monopolized by state-sponsored institutions and societies based in the “capitals” of Moscow and Leningrad.

In examining how Grief achieved global popularity, the author primarily focuses on the community of professionals and civic activists, while largely leaving out actors such as Soviet party and state institutions or art “curators” connected to the Soviet secret services. This omission can be explained by Shneer’s lack of access to archival documents or personal testimonies related to these hidden aspects. The strongest sections of the book are those devoted to the American context and the development of the global market for Soviet photography, whereas the local contexts of the USSR and Kerch are explored in less depth. Nonetheless, this work demonstrates how the histories of occupied territories and dictatorial regimes can be studied — even remotely — by engaging with many people on the ground and incorporating their perspectives.

Translated from Ukrainian by Yuliia Kulish.