Ludwig Wittgenstein. “If an orange could speak”: genius and other nonsense

Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s theories are not the easiest to comprehend. But the life of this Austrian-born thinker has fascinated filmmakers, comic book writers and generations of young people who decided to study philosophy. Borys Filonenko wrote his PhD thesis about one of Wittgenstein’s books. In this essay, he reflects on the philosopher’s paradoxical and witty figure.

I suppose if Ludwig Wittgenstein were to watch Pulp Fiction he would smile at the moment when the adrenaline-revived Mia Wallace tells Vincent Vega the joke about the family of tomatoes. “Three tomatoes are walking down the street – papa tomato, mama tomato, and baby tomato. Baby tomato starts lagging behind and papa tomato gets really angry. He goes back and squishes him, and says, ‘Catch up!’” A play on words: Catch up! – Ketchup!

Wittgenstein enjoyed American movies: he particularly liked musicals and westerns, and would watch with rapt attention while nibbling on pastries. The movie theater gave him the rare opportunity to rest from intellectual labor. There are more than a few anecdotes about Wittgenstein’s peculiar sense of humor. Here is his favorite joke: “A baby bird grows up and leaves the nest. One time it returns and sees an orange lying there. The bird asks, ‘What are you doing here?’ The orange replies, ‘Ma-me-laid!’” A play on words: ma me laid – marmalade.

Thanks to Wittgenstein’s attention to language, while serving at the front during World War I, he “solved all the problems of philosophy”. He announced this remarkable accomplishment in 1918, in the introduction to his manuscript, which would soon gain renown as the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921–1922), or simply The Tractatus. It consists of seven numbered propositions, six of which are elaborated with additional numbered statements. Wittgenstein began writing The Tractatus in pre-war Cambridge, continued during his military service, and completed it while on leave in a fortified building in Hallain after the Austro-Hungarian army retreated to the Trentino mountains. At that time, Wittgenstein was not as fond of nonsense. On the contrary, he was searching for the logical form of a universal language in which there would be no nonsense — only true, unshakable, ultimate solutions to the problems of philosophy. He wrote that all philosophical questions arise from misunderstanding the logic of language and thus present linguistic conundrums. In addition, he claimed The Tractatus revealed how little there is to gain from solving these problems.

In Apostolos Doxiadis and Christos Papadimitriou’s graphic novel Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth, Wittgenstein is depicted on a military mission: he crawls out from his trench and spots a ruin to use as cover to observe the enemy. He takes note of their positions through his binoculars, hides again, and waits. He asks in a thought bubble, “Can this world have a meaning?” A firefight breaks out and lasts for a page and a half. On the following page there is silence; a flare appears in the sky. Wittgenstein stands in a field and arrives at the proposition numbered 6.41 in The Tractatus, which states that the meaning of the world is not within but lies outside the world.

In 1912, at a meeting of the Cambridge University Moral Sciences Club, Wittgenstein had given a speech addressing the question “What is philosophy?” It lasted all of four minutes. Although the discussion went on for much longer than the initial presentation, and the members of the club did not uphold Wittgenstein’s thesis, this event can be considered an attempt at philosophical critique. Four minutes, or seven theses of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, to solve all the problems of philosophy.

Wittgenstein has entered the history of philosophy as one of its most influential contemporary thinkers. He, however, did not think historically. He claimed to have never read a single line of Aristotle. In The Tractatus he made no references to his predecessors. On the contrary, he argued in the prologue that this was unnecessary. He wrote that he would be understood only by those who were already thinking about similar questions. He thanked only Gottlob Frege and Bertrand Russell. Everything else, as far as intellectual influence is concerned, he considered insignificant.

Wittgenstein was one of the foundational authors of the linguistic turn in philosophy, the 20th century’s most prominent development. At the same time, he was particularly interested in what language failed to grasp — and also in what eluded philosophy itself. “All the facts of science aren’t enough to understand the world’s meaning. For this, you must step outside the world!” says Wittgenstein on a winter’s walk with Russell in the above-mentioned graphic novel. Russell challenges his colleague: “Without language or thought, how can you understand anything?” Wittgenstein replies, “Who knows, maybe by whistling?” and attempts to whistle. “It’s too cold for whistling, Russell.”

Alain Badiou called Wittgenstein an antiphilosopher — a special kind of thinker whose position is critical towards both the philosopher and the sophist, who are classic antagonists. The antiphilosopher performs a linguistic critique of philosophy and also critiques sophistry for substituting rhetoric for the value of truth.

Wittgenstein’s influence is connected not only with texts, but also with life. His biography is full of notable themes: from his affluent origins and pressure from his father — a steel magnate, weapons manufacturer, and one of Austria’s richest men — to his rejection of his inheritance and voluntary military service (despite being eligible for a medical exemption). Wittgenstein’s professional identity changed repeatedly: in official documents he listed his profession as “architect”. He worked as a teacher in village schools and a gardener in a monastery. He patented inventions as an engineer; was a decorated soldier; repudiated his title as university professor; and was also an amateur photographer with plans to write a book on the theory of photography. In Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius, biographer Ray Monk situates Wittgenstein’s intellectual development in late 19th-century Vienna, which Karl Kraus described as a “research laboratory for world destruction.” It was home to Nazism, psychoanalysis, Zionism, Secession and Art Nouveau, atonal music, functionalism and the international style in architecture, and logical positivism. In one way or another, Ludwig crossed paths with the leading figures of all these movements. He received his education in the same school as Adolf Hitler; Gustav Klimt painted his sister Margaret’s portrait; Wittgenstein used his family inheritance to finance Rainer Maria Rilke; he constructed a house with Paul Engelmann, who studied with Adolf Loos; he read poetry for the Viennese Group, which elicited Otto Neurath’s suspicion. Given his family and contemporaries, Wittgenstein was taken with suicidal thoughts. The only alternative to death was genius.

Proposition seven of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus states, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” The last sentence has prompted different readings: from the positivist, whereby Wittgenstein put the final nail into the coffin of metaphysics, to the mystics’ praises of silence. In a letter to a Viennese editor, Wittgenstein wrote that there are two parts to The Tractatus, and for him, the second, unwritten one was more important. This part comes after the seventh thesis and concerns ethics, which falls outside the realm of language.

The architectural version of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus was called the Haus Wittgenstein, which Paul Engelmann and Wittgenstein built for Ludwig’s sister, Margaret. Wittgenstein attended to even the most minute details of this project. He designed the door handles, locks, and radiators; he ordered the height of the ceiling to be raised by thirty millimeters to obtain ideal proportions for the room. Ludwig’s sister, Hermine, said that the house “seemed indeed to be much more a dwelling for the gods than for a small mortal like me”. Continuing the analogy, we can say Wittgenstein’s was an uncomfortable philosophy. Over time, though, it changed.

Wittgenstein never published any more texts after The Tractatus (aside from one article, one review, and a children’s dictionary he created during his tenure in the schools of Lower Austria). However, he continued to write and participate in Cambridge University life. The texts he produced after 1929 were collected by his student, the philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe, and his successor, philosophy professor Henrik von Wright, and published posthumously in books such as Philosophical Investigations, Culture and Value, Zettel, and Remarks on Color, which contained previously unpublished, incomplete, and fragmented works. Bertrand Russell and, later, Alain Badiou found the metamorphoses of Wittgensteinian philosophy strange and incomprehensible. Russell introduced a conceptual division between Wittgenstein I and Wittgenstein II, and in the 2000s, Badiou praised Wittgenstein for having the tact to leave his later texts, which “resembled a personal Talmud”, unpublished. The intellectual atmosphere at Cambridge had grown stale. Wittgenstein advised his former student Maurice Drury to leave. When the latter asked his teacher why he stayed, Wittgenstein replied that he breathed his own air.

The people who gathered around Wittgenstein emulated his distinctive manner of speech and dress (I am reminded of Rust Cohle/Matthew McConaughey from the first episodes of True Detective, who could have been the American screen version of Wittgenstein). They also feared him. One of the best popular histories of philosophy is the double biography of Wittgenstein and Karl Popper, Wittgenstein’s Poker, written by BBC journalists David Edmonds and John Eidinow. The book investigates a ten-minute discussion between the philosophers on October 19, 1946, which concluded abruptly when Wittgenstein interrupted Popper’s musings on moral principles, asking the latter to give an example. Wittgenstein was already so riled up by the discussion that he posed the question while waving the burning hot poker he was holding at Popper. This was not the only time Wittgenstein got aggressive with an intellectual opponent. Once, while visiting George Moore, he launched into a scathing critique of the latter’s lecture on a person’s capacity to know their feelings with certainty. Wittgenstein had not even attended the lecture, but he was set off by the announced topic and what those in attendance had told him. He often got carried away by philosophical debates. However, Wittgenstein’s charisma also had another side.

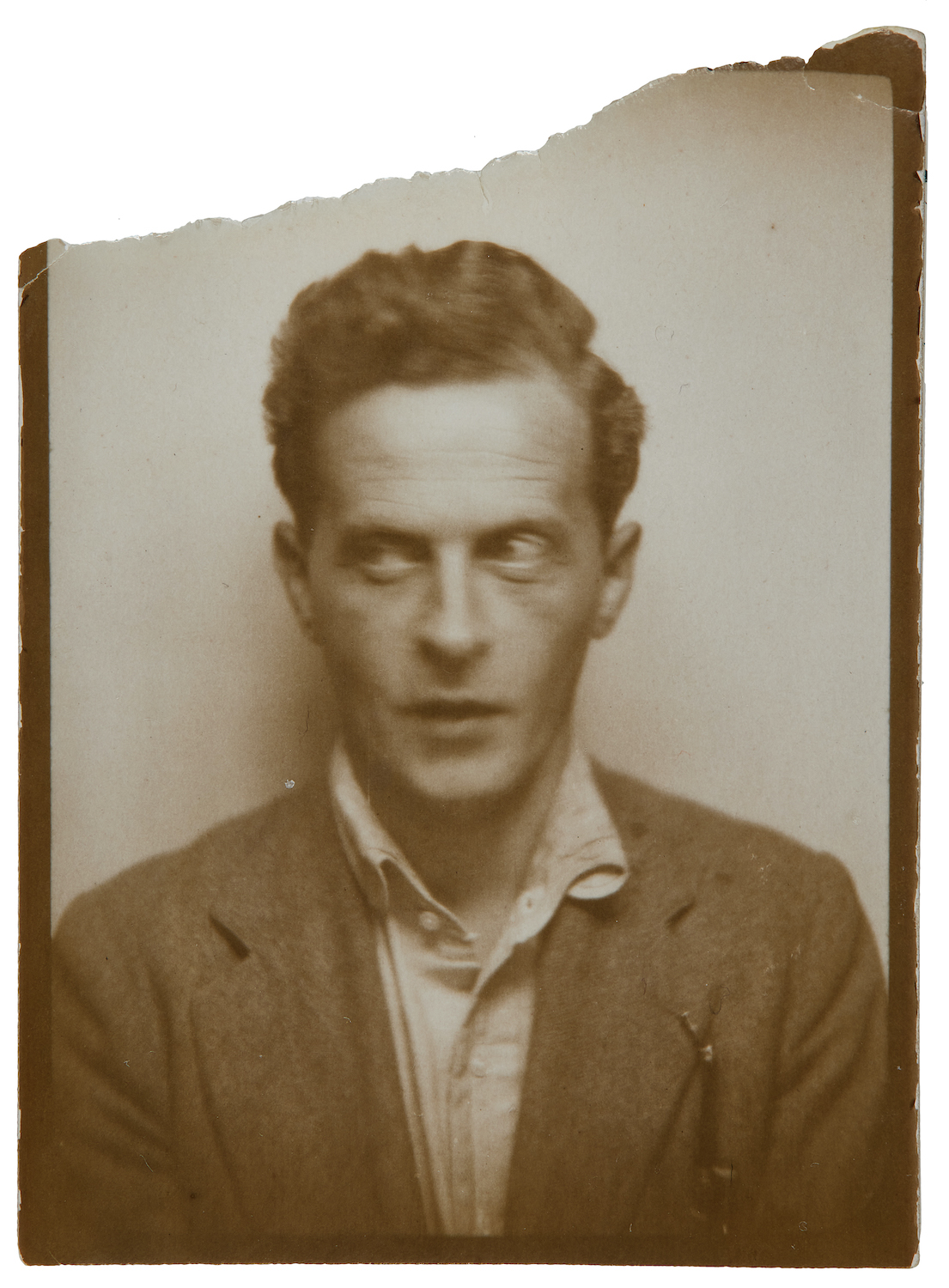

The eyes of the “later Wittgenstein” gaze out from a photo collage in W. G. Sebald’s novel, Austerlitz, with a “fixed inquiring gaze found in certain painters and philosophers who seek to penetrate the darkness which surrounds us purely by means of looking and thinking”. Sebald’s protagonist recalls this gaze while visiting the zoo, observing the lemurs and owls. If we zero in on the bestiary in Wittgenstein’s texts and in those written about him, we will find a variety of creatures: a rhinoceros, beetles, a fly, a duck or a rabbit (depending on which one you see first), and others. He showed the fly a way out of the flytrap as a metaphor for the aim of philosophy (Philosophical Investigations, I 309). Each person has their own beetle (Philosophical Investigations, I 293). The limits of understanding were established with a lion: “If the lion could speak, we would not understand him” (Philosophical Investigations, XI). In Wittgenstein’s favorite joke, a bird spoke to an orange. He carried fruits and vegetables in a mesh bag so that they could breathe.

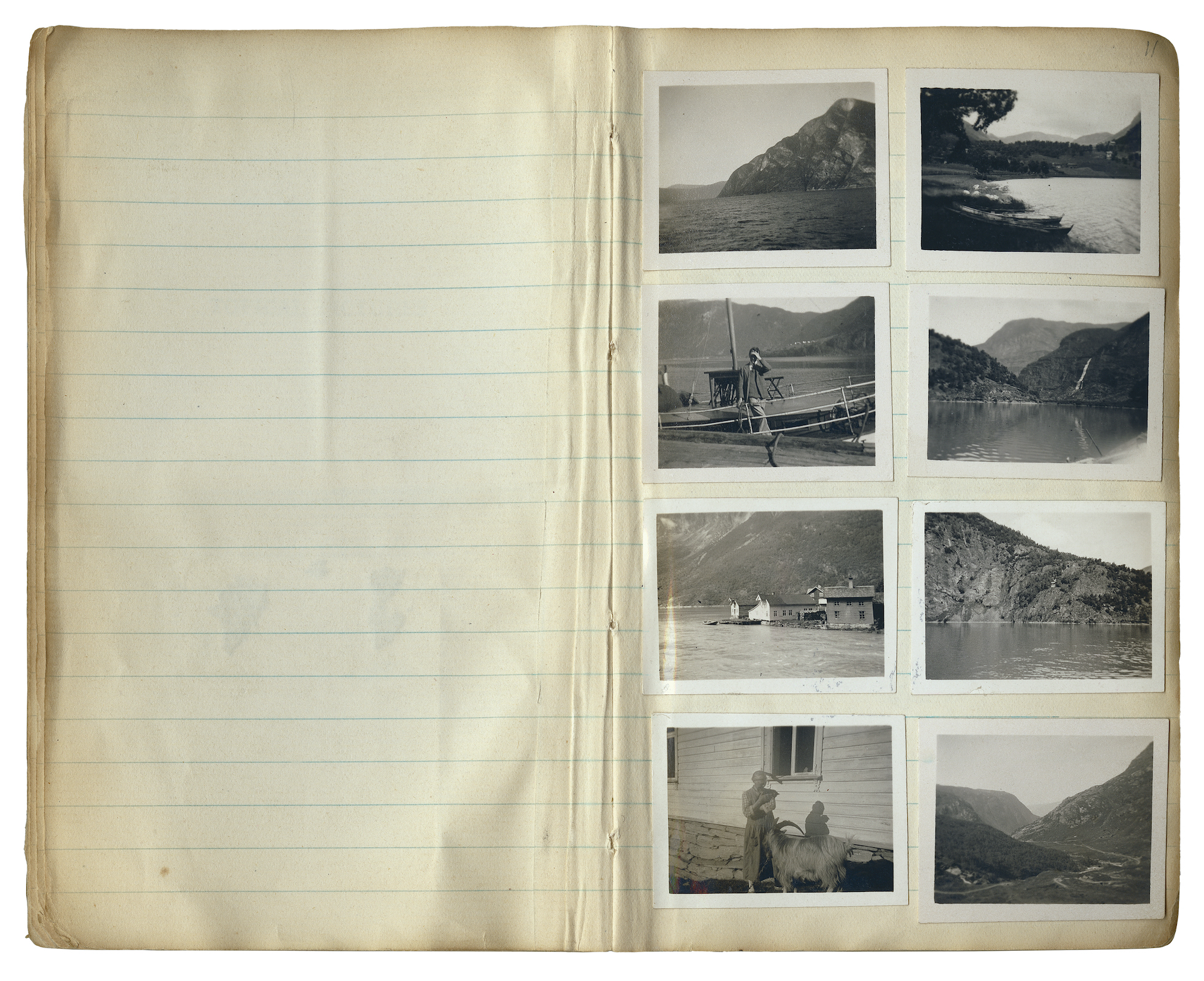

Occasionally, Wittgenstein traveled to Ireland, Norway, and Iceland, where he spent most of his time in solitude. A rumor spread among the fishermen about how the birds would gather around Wittgenstein when he strolled along the shore. It is doubtful that he read sermons to the birds, because he knew that there was no language in which they could understand each other (see Philosophical Investigations, XI). Yet there is a contemporary Ukrainian novel that weaves both Saint Francis, who read sermons to birds, and Ludwig Wittgenstein into the text. The book is Taras Prohasko’s The UnSimple. The main character is named Francis, and there is a tertiary character, an ornithologist, who has memorized The Tractatus and developed a system of encoding based on its propositions. In this system, different species of birds send out signals: “For example, the sentence ‘Each item can be the case or not the case while everything else remains the same’ would be transferred over by one type of bird, by two — another and one — and yet another (one two one). What a sentence like this was to signal should have been figured out on one’s own.” The UnSimple concludes in about the same place as The Tractatus, on the seventh proposition and its mystical interpretation:

“28. From the highest of the trees that Sebastian had planted in 1914 the magpies took flight and flew into the shadows of Petros.

29. Sebastian counted – seven.

30. In the ornithologist’s notebook, seven—Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

31. Of all the proofs of God’s existence, this can be considered the best.”

In the 1930s, Wittgenstein’s research subject, language, no longer claimed universality. He turned his attention to how everyday language was used. For all its deviations and all the misunderstandings that occurred, it still worked. According to physicist Freeman Dyson’s memoirs, Wittgenstein first used the game as a metaphor while watching a football match. This led to a new term – “language-games” (Sprachspiel), which Wittgenstein used to highlight the continuity of language and its usage in specific contexts that have different rules. It follows that the meaning of an expression depends on the situation in which it occurs. William Bartley III wrote: “For the later Wittgenstein the categories of the understanding—of language—were in constant flux.” Language-games are the subject of most of Wittgenstein’s notes (unpublished during his lifetime), which he continuously revised. The epigraph to The Tractatus is a quote from Ferdinand Kürnberger: “whatever a man knows, whatever is not mere rumbling and roaring that he has heard, can be said in three words”. Wittgenstein sought after such perfection in his later texts.

Wittgenstein makes an appearance in Philosophers’ Football Match, a short sketch in The Flying Circus of Monty Python anthology series. He is accidentally playing for Germany’s team against Greece. His jersey bears the classic “9” of a forward, just like the Brazilian Ronaldo.

In 2021, the Leopold Museum in Vienna held an exhibition titled Photography as Analytical Practice, which presented Wittgenstein’s photographs beside the works of John Baldessari, Nan Goldin, Gerhard Richter, Cindy Sherman, and a few dozen other artists. In addition to displaying Wittgenstein’s rare, early photographic experiments, including a handmade photo book and the beginnings of his treatise Laocoon for Photographers, the curators also showed the Nonsense Collection. This is a box containing 127 artifacts, primarily newspaper and magazine clippings, that Wittgenstein and his circle of family and friends had collected over the years. This collection probably accompanied Wittgenstein for a long time as an assortment of moments that caught his attention and deserved to be shared with others. For example, in one of the newspaper columns there was a discussion about how to best translate the word “jazz” into Latin. In another there is a photograph of a sculpture of Einstein in front of a Catholic cathedral, which especially delighted Wittgenstein. Research scholar Joseph Wang-Kathrein writes in the exhibition catalogue, “What insight does the Nonsense Collection lead us up to? This is a question. The answer to which I would not even dare to speculate about.” I suppose we are yet to discover what language-game we are playing here.

I used to have a habit of opening any book I found interesting to the index and checking for mentions of Wittgenstein. If there was no index, whenever I came upon his name in the text, I would underline that fragment in pencil. Now these encounters make me think of that joke: the bird has grown up, having read quite a few of Wittgenstein’s texts and biographies, and has abandoned the nest. After a while, the bird returns and sees a V. P. Twin Bakelite Pocket camera laying there. The bird asks, “What are you doing here?” According to historical research, the camera ought to reply (in the form of a pun, of course): “Ludwig bought three of these cameras and gave two to his friends, so they would photograph their journeys.” This nest of attention to the world, various forms of notation, and language-games is woven in such a way that every time you return you find something new.

It could be in a conversation with Tiberiy Szilvashi about what precedes language during work on an exhibition that includes the film Blue, directed by Derek Jarman (who also directed Wittgenstein); or in the amazement of discovering that Ethan Coen wrote a bachelor’s thesis Two Views of Wittgenstein’s Later Philosophy; or while researching artist Stanislav Turina’s wartime color schemes. The sense of Wittgenstein often lies outside his texts.

This makes the conspicuous absence of Wittgenstein from my university days — or his obtrusive, even irritating, presence in Western academia — seem even stranger. In Gilles Deleuze’s cinematic alphabet, when prompted by Claire Parnet, “Let’s move on to “W”,” the philosopher replies, “There’s nothing in “W” Parnet: “Yes, there’s Wittgenstein. I know he’s nothing for you, but it’s only a word.” Deleuze: “I don’t like to talk about that…” And then there’s a memory I nearly forgot: in Kharkiv, in 2009, or maybe 2010, a visiting German philosophy professor said, “It’s so good that you are concerned with other issues here, because in Europe and the US all you hear is Wittgenstein, Wittgenstein, Wittgenstein…”

Translated from Ukrainian by Lyubov Kovalchuk.

Copy-edited by Larissa Babij.