The power of the camera and archives: a documentary about Leni Riefenstahl

What power does cinema hold? What does it take to make a propaganda film? A deeply manipulative personality, or sheer cluelessness? Andres Veiel’s documentary film Riefenstahl, released in 2024, tries to tackle such questions all at once, weaving together archives and footage about Hitler’s favorite filmmaker.

German filmmaker Anders Veiel is no newcomer to portraying people of complex life choices or dubious political orientations. He decided to make a documentary about Leni Riefenstahl after he gained access to her personal archive: 200,000 photos, clippings from newspapers, documents, parts of her films, home videos, recordings of phone calls, diaries, memoir drafts. Mixing this impressive number of records with footage from TV shows and interviews that Riefenstahl took part in, Veiel put together a 110-minute-long attempt to understand her character. Riefenstahl not only brought Nazi propaganda onto the silver screen, she magnified it by using all the instruments cinema could offer.

Born in 1902 into a wealthy family (her father was a successful businessman), Riefenstahl wrote poetry as a child and started her career as a dancer. In the 1920s she fell in love with cinema, especially “mountain films”, which were a success at the German box office. After 1926, she starred in several such films, starting with Arnold Fanck’s The Holy Mountain, and continuing with The White Hell of Pitz Palu (1929), co-directed by Fanck and G.W. Pabst. Pitz Palu is considered one of the most significant films of the “mountain films” sub-genre, whose popularity was described by German film historian Sigfried Kracauer as a confirmation of “the surge of pro-Nazi tendencies during the pre-Hitler period”.

Riefenstahl debuted as a film director with The Blue Light (1932), a film which brought her into the focus of Adolf Hitler. She boasts about this in footage used in Veiel’s film, also stating that this movie was the most important part of her career. Riefenstahl’s Jewish co-authors, Carl Meier and Béla Balázs, who wrote the script, and producer Harry R. Sokal fled Germany shortly after the film was released and the Nazis came to power.

The Blue Light also brought Riefenstahl onto the international scene: it was screened at the Venice Film Festival, which was held for the first time in 1932, established by Benito Mussolini’s government. She would return to Venice several times: in 1935 and in 1938, winning awards for her most famous Nazi propaganda films, Triumph of the Will and the two-part Olympia.

In 1939, after Nazi Germany invaded Poland, she followed the troops as a “war correspondent”. Veiel dwells on this point of her biography in his film, portraying her both as a ruthless participant in the events, and as someone who didn’t fully understand what was going on. Later, she preferred to claim she knew nothing about the mass extermination of Jews, although evidence shows otherwise. According to a letter written in 1952 by a Wehrmacht adjutant and which Veiel found in Riefenstahl’s archive, twenty two Jewish inhabitants of the Polish town of Końskie were killed after Riefenstahl asked for them to be “removed” from a ditch where they had been working, surrounded by Nazi soldiers. Their presence did not make for “good background for filming”. Riefenstahl always denied any of this: “I have never seen any atrocities.”

In 1940, She began filming Lowlands, an expensive opera drama project she’d been trying to make for some time, directing, writing and starring in it herself. The production of this film involved Sinti and Roma children as extras. Photographs of them are also included in her archives (with twisted captions, such as “Siegfried, a test for Leni’s patience”). As Veiel shows, after the filming, most of these people were sent to Auschwitz where they were killed. Riefenstahl never acknowledged this, insisting she knew “for a fact” that they had survived.

After 1945, Riefenstahl was put on trial by the Allies. She spent some time in different prisons and under house arrest, but eventually was named a “Mitläufer” of the Nazi regime, since she never was a member of the Party. She tried to return to filmmaking, unsuccessfully.

Later, she reinvented herself as a photographer. During several trips to Sudan in the 1970s, together with her partner-slash-assistant Horst Kettner, she photographed the local Nuba tribe. She later released several photo albums. One of these books, The Last of the Nuba, was heavily criticized by Susan Sontag, who focused mainly on the book’s jacket text, which was full of inaccuracies and whitewashed Riefenstahl’s work for the Nazis. “Although the Nuba are Black, not Aryan, Riefenstahl’s portrait of them is consistent with some of the larger themes of Nazi ideology: the contrast between the clean and the impure, the incorruptible and the defiled, the physical and the mental, the joyful and the critical,” Sontag wrote in The New York Review of Books, adding that the release of such a book felt like the culmination of Leni Riefenstahl’s rehabilitation at the time.

Riefenstahl fought for such a rehabilitation until her death in 2003, at the age of 101. With the help of a small army of lawyers (Andres Veiel claims there were 50 of them), she sued a lot of people for defamation whenever they dared recall that she had been a Nazi propagandist. Throughout the years, Riefenstahl took part in numerous talk shows (reportedly getting paid huge honorariums) in which she continued to defend herself, placing politics and arts on opposite sides of the spectrum. She would say she’d merely been “commissioned to make those films” by Hitler and that “no one would have refused”.

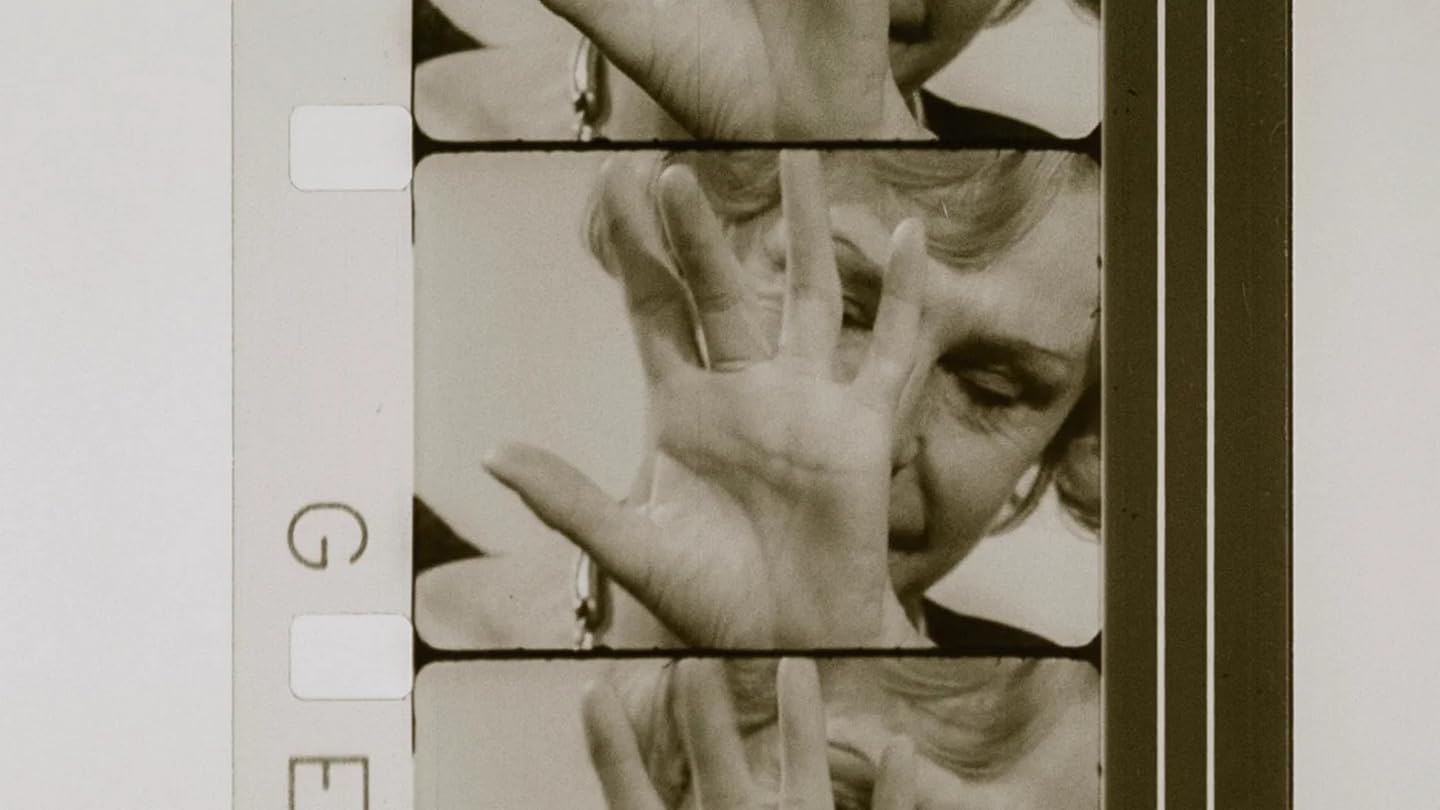

The director of the Riefenstahl documentary intended to “show her as a human being and not just point at her, stage a trial and say she's the embodiment of evil”. But the image of Riefenstahl gazing, flirting, shouting, grinning, isn’t so easy to get over. It is the image of a woman who knows the power of the camera perfectly well. All her life, she was aware of its ultimate magic: no matter how awful the atrocities it may fuel, its reputation always somehow stays clean.

Leni Riefenstahl directed everything: not only her films (which were, by the way, applauded by film critics and festivals for a long time after 1945), but the holistic portrayal of her life. The archive, partly shown in Veiel’s film, provides a piercing glance at Riefenstahl’s manipulative personality.

Her huge archive, stored in 700 boxes, contains press clippings, photos, and other memorabilia of her on- and off-screen presence, but also recordings of phone calls she received, especially after appearing in talk shows. As most of those who called her clearly had pro-Nazi sentiment, we see that Riefenstahl kept feedback that soothed her self-esteem. Despite the film industry’s many accolades, she was still reminded of her Nazi past by many commentators, and she did not much enjoy it.

Riefenstahl, the documentary, juxtaposes its protagonist’s statements with сlear evidence drawn from various archives, sometimes even her own. Her insistence that she has been “enchanted by Hitler, like 90 per cent of people” sits alongside numerous photos of them shaking hands, walking together, or exchanging flowers. It was hardly a passive “enchantment”. There’s also a Riefenstahl quote suggesting that the premiere of Olympia should be postponed until Hitler’s birthday on 20 April. Her demonstrative “cluelessness” about genocide is shown alongside lists of the Sinti and Roma people she included in her film, and who were soon afterwards massacred. Her claims to have filmed “reality as it was” at the 1936 Berlin summer Olympics are mentioned next to a complex shot of a Greek statue mutating into the living body of an athlete.

Sometimes archives, even meticulously selected, fail to deliver a comfortable, curated picture and instead provide the raw truth. Leni Riefenstahl was far from innocent, Anders Veiel’s film tells us. Such a statement may seem audacious in its sheer self-evidence. But where does it leave us, the viewers? There’s no simple answer.

The first time I watched Riefenstahl was in a Berlin cinema one Saturday evening in the autumn of 2024. The theater was full; people had brought popcorn and seemed to enjoy watching scenes where Riefenstahl, shown in her 70s and 90s, with her faded beauty, in ruthless close-ups, tried to pull herself out of the shadow of Nazi crimes. Footage of her trip to Sudan, sponsored by various German businesses, including (oh, the irony) Persil, was awkward to watch. Yet the audience laughed. Were spectators attempting to distance themselves from Riefenstahl, the obvious propaganda agent? The trope of the “crazy old lady”, a Sunset Boulevard’s Norma Desmond-type of character, came to mind: someone who had completely lost herself in the intoxicating gaze of the camera. It helped us viewers — intentionally or not— sigh with relief: we are not like her.

That same autumn of 2024, another premiere was organized at the Venice Film Festival: the Canadian-French film Russians at War, directed by Anastasia Trofimova. A former “correspondent” for Russia’s state propaganda channel Russia Today, Trofimova gained access to Russian troops taking part in the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Dressed in their military uniform, she filmed Russian soldiers and interviewed them about their lives on the frontline. At the press-conference in Venice, Trofimova said, “If war crimes were committed, obviously you would see them on screen, but in the seven months I was there, that was not my experience.”

Riefenstahl was once asked whether footage of 1990s racist protests against immigrants in Germany stirred any memories in her. She replied, “I never witnessed this in Germany. It never happened.”