A flow of change. The meaning of water in Ukrainian 1960s cinema

For Ukrainian film directors of the Soviet 1960s, water on screen served as an indicator of era shifts, of notable aesthetic and worldview changes. Water helped touch on topics which had been tabooed — corporality, grieving, and the painful losses inflicted by Stalinist repressions, the Holodomor and World War II. During the decade of “Thaw”, directors dared to criticize the abuses of nature more openly. Water shown on screen not only illustrated the reclaiming of a person’s corporality, it also gave the ability to speak of the non-rational dimension of life, and to move from Socialist realism to poetry.

Water is everywhere in the motion pictures of the Soviet “Thaw” period: foaming as sea waves, gathering in puffy clouds and pouring rain, glistening in wet puddles, running down gutters, suspended as mist, mirroring as lakes, and mesmerizing like turbulent river streams.

Water, or a lack of it, is often spoken of, it is drunk, drawn into containers, it is used to do laundry, to wash oneself and to clean up — windows, floors, kitchenware. Water is featured in film titles too: Spring on Zarechnaya Street, Poem of the Sea, Entering the Sea, A Well for the Thirsty, White Clouds, Spring Rain.

Cinema responded to the social and political processes of the “Thaw” period with a delay. Although a number of films which didn’t fit within the boundaries of Socialist realism were released as early as the second half of the 1950s, directors shot landmark pictures towards the close of the “Thaw” period, or even shortly after it ended. As with physics where time and energy are necessary for water to pass from a solid state to liquid, so it is with culture: it took Ukrainian cinema almost ten years after Stalin’s death in 1953 to wake up from the stupor.

One gets the impression that the authors couldn’t entirely believe that the era of Stalinist repressions, the hunt for enemies from within and without and harsh censorship, were seemingly over, with a new era beginning in which freer statements are allowed. Those changes were in the air; artists felt them, but weren’t sure about how the situation would evolve and how the system might react to the manifestations of free thinking over time. This wasn’t about fear for oneself above all, it was about the desire to get their message across to the viewer, slipping through the filters of censorship (which had then started allowing noticeably more films to make it onto the screen). This is possibly why many “Thaw” era films speak to the viewer in a language of codes, associations, ambiguous symbols and metaphors. Besides, this new imagery and visual emancipation avenged the years of dry literature-centered Socialist realism.

The return of nature

The image of water in the “Thaw” period comes across, among other things, as a retort to the technocratic approaches of the 1920s and 1930s when nature was predominantly treated as a resource for the country’s production and industrialization. The set phrase “water resources” comes into use. 1920s and 1930s Ukrainian cinema often depicts a Soviet citizen forcing the massive streams of the Dnipro River into the concrete banks of dams and large-scale construction projects. One might say that the construction of the Dnipro dam becomes the star of the 1920s Ukrainian cinema, as seen in a number of films: The Eleventh (1928, Dziga Vertov), Wind from the Rapids (1929) and Dnipro in Concrete (1930, both by Arnold Kordum). Filmmakers even employ animation to provide a vivid explanation of how the Dnipro’s riverbed would change, to what extent the water level would rise and which villages would go underwater.

The 1920s also mark the emergence of films showing water flowing freely and in picturesque ways, films creating strong poetic images. Take, for instance, the spring flood in Mykhailo Kaufman’s documentary In Spring (1929) which transforms Kyiv into Venice and forces citizens to move around in boats. Or the spring entertainment of boys in Kyiv’s Podil neighborhood — riding ice floes in the Dnipro’s swift waters, in Aksel Lundin’s Adventures of Half of a Rubel (1929). And of course, the unforgettable heavy rain washing up apples and pumpkins at the end of Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930).

The new attitudes of the “Thaw” era first trickle through cracks into films which at a first glance could be classified as “high” Stalin style. But a more careful examination of those motion pictures reveals details which ruin an ostensibly proper Socialist realist structure. An example of this is Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s Poem of the Sea (1958), completed by his wife Yuliya Solntseva after the director’s death. The film’s protagonists participate in the construction of the Kakhovka dam and prepare for the village’s flooding. Even though the construction work is depicted on a grand scale and with great optimism, some characters take the liberty of being sad about their paternal garden and spring-well which will soon end up at the bottom of the sea, and more than that — they protest against the flooding and evacuation. It is telling that those characters are Ukrainian-speaking or speak with a heavy Ukrainian accent.

It’s unclear whether Dovzhenko does this on purpose, but he carries the Stalinist narrative to the point of absurdity, thus revealing its artificiality and remoteness from reality. The linguistic dimension is particularly indicative of this: characters say that they “are building a sea”, congratulate each other “on the new sea, new happiness”, “on the birth of the sea” and swear by the sea as “the most sacred thing.” Socialist realist narrative is at odds with the film’s visuals, with their poetic imagery and the almost surrealist inserts of dreams, including a legend of Scythian kings.

The return of private life

Film director Kira Muratova — a VGIK student at the time — got her practical training on the set of Poem of the Sea. The theme of water is present as early as in her graduation work Spring Rain (1958) co-shot with her husband, Oleksandr Muratov. This film’s young protagonists show rather frivolous behavior for the cinema of the times: they ride as “fare-beaters” on a train instead of doing “normal work”, they walk in the rain, fight, make up, kiss in an entrance lobby — doing virtually everything their French contemporaries, for instance, could be doing in New Wave films. Even though an educative anti-alcohol story arc was included in the film, making it more down-to-earth, the picture’s essence is rendered by the protagonists’ dialogue: when asked “What are you up to?” the girl responds: “Nothing, just drinking water.” This kind of unorganized, unstructured pastime, be it during working hours or at one’s leisure, was in Stalin era cinema only proper to marginalized characters or “enemies of the people”.

The Muratov spouses’ movie brings to mind another “spring” film full of rain, puddles and youthful passions — Spring on Zarechnaya Street (1956), by Feliks Mironer and Marlen Khutsiev, which was a box office success and brought everyday life back to the Soviet screen. Although the film’s characters are properly employed as per Soviet standards (with a teacher and a shock, high productivity worker), their relations, emotional struggles and household interactions take up a disproportionately large amount of screen time, and the film is thus markedly different from the usual production dramas.

Despondence is palpable behind the similar ease and youthful lightheartedness of Muratova’s first independent feature-length film, Brief Encounters (1967), which the director used to call a “provincial melodrama”. The plot centers around a love story as well, but this time it is made more complicated by the circumstances and conditions of life. The female protagonist, public official Valentyna portrayed by Kira Muratova, is responsible for a question of national importance: ensuring water supply, in a city where water is always scarce. Her lover Maksym, a geologist, played by the singer Vladimir Vysotsky, practically leads a nomad’s life: camping trips, guitar singing, vague plans for the future. Yet another character emerges in this melodramatic story, Nadia (Nina Ruslanova).

The theme of water comes up as early as in the first images of the film, when Valentyna plods away at her official speech and sadly looks at a pile of dirty dishes. “To wash or not to wash, that is the question”, the heroine ponders aloud. We observe various vessels, full and empty, throughout the film, we listen to discussions about water or its absence, we see taps from which water runs and those from which it does not. The plot unravels without keeping a chronological sequence due to the constant flashbacks of both heroines, and there is substantially more water in those recollections than in the present, which Valentyna describes as “a long-drawn pause.” Water in this film stands for life, its transience, fulfillment with meaning, connection to reality. The characters lack all of that, regardless of their energetic attempts to change the situation. Instead of rain and river streams in Spring Rain the characters of Brief Encounters watch crawfish boil. It seems the characters’ life has narrowed down to the size of a cooking pot with boiling water, a pot into which they peek with admiration and curiosity and in which they see their reflections alongside the crawfish. The persistent search for water and its ongoing lack convey a feeling that the “Thaw” epoch is ending, and that a new period is beginning, also water-themed metaphorically — the era of stagnation.

The return of the Irrational

Socialist realism was nowhere near representing reality as it was; instead, it was meant to demonstrate what it should be, and so it also employed techniques from fairytales and fantasy films, incorporating dreams, reveries and memories into plots. But the conventionality of those far-fetched inserts had to be exactly the sort that would enable a viewer to imagine themselves as one of the characters somewhere in the vast future, and to actively aspire to it. “Thaw” era cinema reveals a completely different dimension of human existence - a mythical or even mystical one. Water becomes an important visual image, supporting a shift from the social and common-life representation of reality to a mythopoetic and associative depiction. Directors often find the material for such films in popular culture, folklore, as well as in modernist prose which reinterprets these sources.

The characters of Mark Donskoi’s film At a High Cost (1957), drawn from a short novel by Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, are constantly somewhere near the Danube river, either on one bank or the other. The plot is set in the 19th century; two villagers in love, Ostap and Solomia, attempt to flee their master to the other side of the river — to the Turkish land where runaway villagers and Cossacks established the Danubian Sich after the destruction of Zaporizka Sich. When the master’s sentries chase after the serfs on horseback with rifles and hound dogs, the sedges, reeds and mist over the river provide the heroes with temporary refuge. The river in the film becomes a watershed between different cultures, between freedom and captivity, even between worlds, offering a chance to overcome temporal and spatial limitations. The film’s style is unrealistic throughout, but this scene seems the most chimerical: having reached the Danube’s bank, the young couple hears a sad song, follows the sound along the river and suddenly comes up to a deathbed farewell ceremony for Ostap’s uncle. There he lies on the riverside, on his deathbed, while sworn brothers, haydamaks, burn fires and char their Chaika (Ukrainian for seagull) boats. Their song is what the protagonists have “heard”. The old man’s last cry is heard, and the camera brings our attention to the panorama of the river, as if the deceased’s spirit hovered over it.

Images of water associated with death and danger, similar to those expressed by Donskoi, are also found in Sergey Parajanov’s Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964). Water in the film accompanies the characters, in particular in transitions between different ages or social statuses. Naked children splatter merrily in a rivulet — and several shots later, they are a boy and a girl in love. The characters cross the river to meet Ivan one last time before his departure. Farewells are made in the heavy rain. The scene of the girl’s death is almost completely “woven” with water - with the mists and turbulent streams of the mountain river where Ivan and other Hutsuls search for Marichka. Ivan will be persistently looking for the girl’s image in the water and will ultimately see it. In one of the scenes, the hero is shown as if in the middle of the water, and his lips touching the surface resemble a kiss with the beloved one.

We see water least of all in the Loneliness episode depicting Ivan’s emotional struggle after Marichka’s death. Water is featured only once here, when he washes his shirt in the spring -obviously meant to mark the transition between seasons and a certain change in the hero’s psychological state. Color disappears in this part of the film, along with water, which returns for some time with the appearance of Palagna. Older women give Ivan a ritual bath before the wedding ceremony. He crosses the river on a raft on his way to the wedding. For the last time, Ivan is bathed after his death.

In the films of this period, water — the river in particular — becomes the embodiment of danger, unpredictability, death and at the same time it represents a powerful force, life and hope. As in Ukrainian folklore, water is often associated here with rituals of passage, a change in social status. This stands in vivid contrast to Socialist realist dramas, where the river is commonly an idyllic space for lovers’ rendez-vous and romantic boat rides.

The return of the body

Water in “Thaw” era films also evokes a person’s redemption of their own body, predominantly considered as a resource during the period of active industrialization and collectivization. People in Socialist realism cinema are virtually bodiless, machine-like creatures performing a certain function, both within the film plot and in society at large. A human’s physical needs usually come second or third after work and civil duties. The expression “He who does not work shall not eat” was not only a widespread motto but was incorporated in the 1936 Soviet Constitution. Positive characters in Socialist realist films forego sleep and other needs for the sake of labor feats. Having accomplished those, they are seated together below Stalin’s portrait at long tables covered to the brim with food and drinks. But even then, there is yet another obstacle between the heroes and the quenching of hunger — long solemn speeches. For instance, in Leonid Lukov’s picture The Miners of Donetsk (1950) the characters remain standing with full glasses, not having had the chance to drink when the film ends. Stalin era cinema thus teaches Soviet people to postpone the satisfaction of physiological needs until better times or, ideally, until the wonderful communist future. “Thaw” era films overcome those obstacles: a person does not only eat and drink when they want to, but also discovers other corporal needs, including sensory ones.

Nude scenes are hard to find in Stalin era cinema; however, they were present in the 1920s pictures. For example, the scene of girls bathing in Taras Triasylo (1926) by Petro Chardynin, or a most famous one: the heart-breaking grief of a naked bride after her lover’s death, in Dovzhenko’s Earth. Even though censors forced filmmakers to cut out this episode (and also the scene of filling up a tractor with urine), the film still retains a lot of “sedition”, including when Dovzhenko depicted villagers made of flesh and blood: not only do they eat apples and watermelons or nibble sunflower seeds, but they also caress each other, and they live in the midst of heavenly nature which freely bestows its fruits upon them. With that in mind, the motivation to enroll in kolhosps does not seem especially justified plot-wise.

During the “Thaw” period, a naked body returns to the screen as early as in Donskoi’s picture At a High Cost, showing a girl bathing naked in the river; next is the above-mentioned episode with children in Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, and finally, Leonid Osyka’s short film Entering the Sea (1965). Having viewed Osyka’s film, Parajanov suggested naming the Kyiv Film Studios after the beginner director — as recollected by the picture’s score composer Volodymyr Huba.

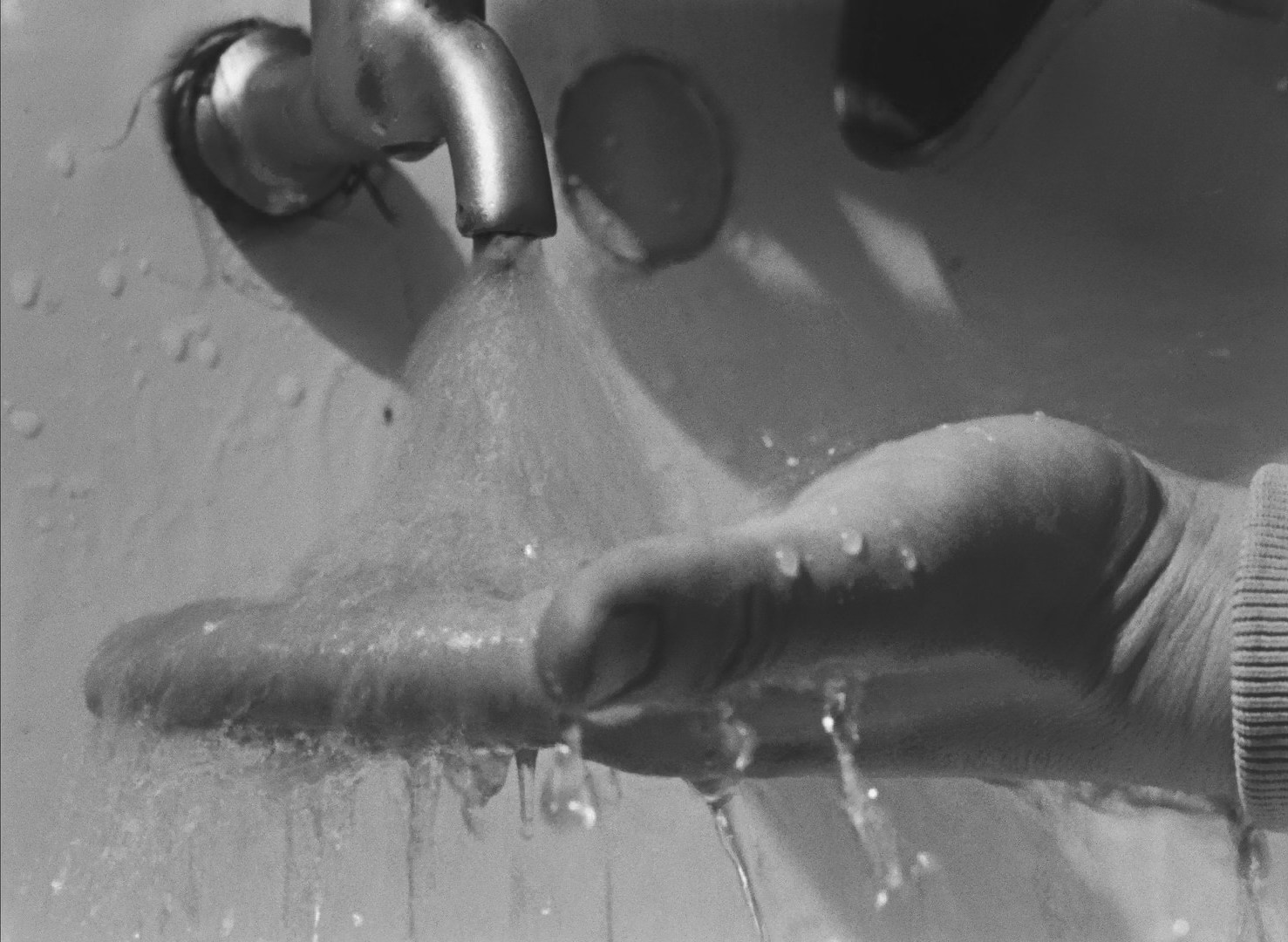

In Entering the Sea we first see a crowded beach: with not enough space, people are even sunbathing standing. A woman holding a small girl gently wades through this hot mass of bodies, and suddenly the image becomes blurred, and those two find themselves on an empty beach; the sea splatters, and a solidly built man’s figure emerges in the fuzzy shot. The film features a lot of touching: characters cover themselves in mud, touch the water slowly and with enjoyment, immerse themselves, run mussel shells through their fingers and sift them; the woman lies, almost completely covered with shells, the girl carries water in her hands and sprinkles the woman, shades her eyes with the shells. The characters seem to merge with the surrounding landscape. The sole object disrupting this idyllic setting is an inflated tire. At first, the girl caresses it with her wet hands with obvious pleasure, plays with it, but then the tire tumbles threateningly after her, and the man stops its movement with a strong hand; a hand strokes hair, now it is a woman’s hand, and the man moves towards the sea and disappears. The girl and woman sadly gaze after him and are alone on the seashore once again. This episode is backed up by the dramatic avant-garde music of composer Volodymyr Huba, giving room to interpret the scene as the loss of a male protector. Next, the woman teaches the girl how to swim and finally the girl swims in the sea herself. Water in the picture is a metaphor of life: parents help the child find her feet in it when she “goes into the sea”, embarking on her own voyage ultimately. The film contains a great amount of sensuality and sensory interactions which might bring to mind the term coined by theoretician Laura Marks: “haptic visuality. This visuality functions by means of so-called “tactile vision.” Thanks to this technique of filming, viewers can feel what they see on a corporal level, as if they were touching things displayed on-screen.

Haptic touch-scenes are also observed in another picture largely dedicated to the human body: Quarantine (1968) by female director Sulamif Tsybulnyk. A dangerous virus is accidentally released in a laboratory, and five employees are forced to stay in quarantine to prevent contamination. Depicting the characters’ psychological state, the film brings the viewer’s attention to their bodies too: bodies which are potential virus carriers. Viewers are involuntarily provided with a diagnostician’s point of view: they thoroughly examine the behavior, movements and facial expressions of the heroes, they follow their way of talking, becoming the first to notice the development of the dangerous disease. This is because the film’s main element of suspense, undisclosed almost until the end, revolves around whether the contamination actually happened or not.

Water has several meanings in Quarantine. Firstly, it reads out as an attempt at purification. Practically incessant rain outside the laboratory windows seemingly washes away the dirt from the streets and represents the clean, uncontaminated condition of the city up to that point. Besides, the laboratory chief keeps asking his subordinates whether they have gargled; there are repeated discussions about bathing. The scene in which the heroine takes a shower is interesting: in terms of stage direction (the framing, the actress’s movements, the camera work) it much resembles the beginning of Hitchcock’s iconic scene in Psycho (1960). The resemblance with this classic thriller also appears in the cameraman’s manner, especially in nighttime episodes and in shots featuring rain, which separates the unwilling laboratory residents from the rest of the world. Rain is also often an acoustic player in the film, with its sounds turning into dissonant, alarming music written for the film by the avant-garde composer Valentyn Silvestrov.

The return of memory and the right to grieve

In the 1910s–1940s, the people of contemporary Ukraine’s territory lived at the limit of endurance and human capabilities — they were subjected to World War I, the October Revolution, Bolshevik occupation, collectivization, industrialization, five-year plans, the Holodomor, repressions, war, the Holocaust, post-war reconstruction and other related problems. Despite all of this, they had to look with optimism to a bright future, hoping that someday things would get better. It was expected that the Socialist realist art, in particular cinema, would create an image of this future.

In the “Thaw” period, probably for the first time in the existence of the USSR, artists managed to pause, look back and try to talk about the past more openly, to the extent it was possible at that time. But the creation of a collective memory was still controlled by Soviet power: even after the debunking of Stalin’s personality cult, his crimes never made it to Soviet screens.

Any rethinking of World War II wasn’t discussed either: Soviet people had to feel two basic emotions: anger towards the enemy and joy because the Soviet Union had won (single-handedly). In his book Everyday Stalinism, historian Serhii Yekelchyk gives telling titles to the first two chapters: “Hate as a civic duty”, “Stalinism as a celebration.” In the second chapter, he notes that Soviet power did not really support the commemoration of fallen soldiers individually: even during memorial ceremonies, the key issue was the expression of gratitude towards Stalin, since it was believed that victory in the war was primarily his merit. Such rhetoric can also be seen in Stalinist films about World War II, and this topic remains today the “sacred cow” of Russian propaganda.

Instead, in “Thaw” era cinema, the theme of grief and a rethinking of the tragic pages of the past appear even in films where we don’t expect it. Film expert Olha Briukhovetska describes this in her article about the movie Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. Yet some films did try to speak more directly about the traumatic experiences of the first half of the 20th century. Probably because of this directness, films such as A Well for the Thirsty (1965) by Yurii Illienko, and Conscience (1968) by Volodymyr Denysenko were banned. White Clouds (1968) by Rollan Serhiienko was censored and issued in limited release only. Kyiv Frescoes (1966) by Serhii Parajanov was not completed at all. Water plays a crucial role in each of these films.

The central image of Yurii Illienko’s film is a spring from which the old man draws water and gives it to others to drink. Water here represents the memory this man preserves and passes on. The film was shot in the form of surrealistic visions, dreams and memories. The camera often stops at old photos, we hear the voices of children and adults, without seeing them. Unreality is added by contrasting black-and-white images and freeze-frames. During the heated discussion about the film in the production studio, the experts present came to the conclusion that it was a requiem film, but not everyone agreed that this genre was legitimate for Soviet cinema. The song “Oh, woe, woe, at such a time” is heard in the film several times. Vigilant censors taking part in the discussion raise a rightful question that hangs in the air: “At what time exactly?” Obviously, it is primarily about World War II, as evidenced by the monument to the Unknown Soldier brought to the village. A worker with a cigarette in his mouth is pointedly indifferent when “unpacking” a statue from the wooden cage in front of the villagers. Several older women begin to cry bitterly; apparently, the replacement of lost husbands and sons by a stone figure does not bring them any relief. The old man with the coffin’s plank walks away — he has his own rituals to honor the dead. Again, he continuously draws water from the spring and gives it to the soldiers who pass by in ranks, casually asking whether his sons are among them. Suddenly, a soldier approaches, tries to drink but says indignantly: “How is that, father, there is no water, only mud remains!” A shot is heard, the soldier falls, and a dark liquid resembling blood flows from a hole in the bucket. It is the only phrase in Russian in the entire film. During the above-mentioned discussion, film critic Hryhorii Zeldovych noticed an “ambiguity” in this episode, despite the generally positive assessment of the film. The lack of water here can be interpreted as a loss of connection with ancestry memory, due in particular to russification.

Rollan Serhiienko’s film White Clouds is also based on recollection. A son learns that his father is dying and travels across Ukraine to bid him farewell. At the beginning, an off-screen voice warns that this is a sad story because it is a story of death. The film’s melancholic mood is enhanced by the atonal music composed by Valentyn Sylvestrov. Moving in space, the main character also gradually moves back in time — to the period of forced collectivization, the Holodomor, and the war. During this psychological road movie, clouds of memories constantly hang over the hero. In one of the flashbacks, the father tells his young son that the round white clouds bring rain. This phrase rhymes with another that comes later. The hero meets on a bus an old woman he knew; she recalls the time when he was a boy playing with friends on a barn floor and she secretly poured wheat into their pockets. “You were so blue, hungry and thin”. This was actually the first time the Holodomor was openly mentioned in Ukrainian cinema: 1968. Next, the woman asks what happened to all those “urchins” whom she saved from starvation. They survived, grew up, but then almost all of them died during World War II. “That’s why you all come in my dreams before the rain — dead people appear in dreams before the rain”, the woman says bitterly. The rain in White Clouds will never start, but at the end we see the hero’s father standing joyfully under a “rain” of wheat. Rollan Sergienko tells about the harshness of the 1920s, Stalinist repressions, camps and war, through the women’s memories in his other work, Declaration of Love (1966). This documentary film ends with rain and an unexpected shot from the talented camera operator Eduard Timlin: trees with brilliant light crowns, standing in dark water. This scene is like a metaphorical summary of what is told in the film.

Serhii Parajanov’s film Kyiv Frescoes was supposed to be dedicated to the theme of post-war Kyiv. Fifteen minutes shot by the film director and the camera operator were kept as Oleksandr Antypenko’s “camera tests”. But the script, which gives a full idea of the film, survived: today this text can be read as high quality impressionistic prose. While previous films use the image of water as a means of recollection, water in the unfinished Parajanov film also reads as an attempt to distract, a catharsis and farewell to the past. Events shown in the film were supposed to take place in the course of a single day in Kyiv, namely on May 9, 1965, during celebrations for the twentieth anniversary of victory in World War II. However, apart from the official celebrations (salutes, flags, monuments, uniforms with decorations and medals), memories of the war live on in the capital in another form: wheelchairs, widows, orphans, Singer sewing machines, and the nightly terrors of those who managed to survive — none of this ever left the city.

The first fresco begins as follows: “A man woke up from the cold... It smelled of kersey... Water was gurgling somewhere...”. Kersey boots and water appear throughout the film script. At night, three soldiers approach the main character for matches and boiled water. The host invites them to stay overnight. The soldiers take off their boots and begin to wash the floor. The city is constantly washed by rain. Parajanov describes this through images of wet asphalt, puddles of water, the smell of dampness, wet clothes... The director tries to talk about the difficulties of returning to civilian life after the war has ended, a traumatic experience still present in the city twenty years on, with unprocessed traumas and unspoken losses coming back in unexpected ways. Official Soviet rhetoric does not help cope with the experiences of the war. It is present in the film visually (in footage of the Eternal Flame memorial, at the beginning) and acoustically, with the solemn song “The Motherland hears, the Motherland knows where her son is flying in the clouds...” sounding like mockery in the film’s context.

Water as an attempt at forgetting and cleaning is also present in the banned film Conscience (1968) by Volodymyr Denysenko. The author made this film based on a true story with almost no budget, together with his students from the Kyiv Karpenko-Karyi Institute. The film describes events in an occupied village during World War II but, as one can tell from its title, it focuses primarily on the characters’ feelings. Water here is connected with situations of ethical choice. A German soldier washes his hands thoroughly after shooting civilians. Collaborators on a bridge above the river decide whether to shoot their fellow villagers. Passing through a traumatic experience is also connected with water: one can interpret the last scene, in which a boy who survived by miracle sits by a waterfall, as if nature were “crying” with people or in their place. The similarity between film directors Parajanov and Denysenko is not only found in cinematographic “free thinking” and the fearless disclosure of the theme of war, but also in their biographies: both of them survived political repression.

The “Thaw” period is sometimes called the “illusion of thaw” because it was a short-term window of opportunities, used by Ukrainian film directors to the fullest. The image of water takes on much importance in films of that era in that it opens up many possibilities for interpretation and introduces ambiguity, which Soviet censors were so wary of. The imaginative world of “Thaw” period films is really interesting to interpret, but it often resists interpretation since it aims for a certain perception of emotions and the body, instead of rational understanding. So the best thing you can do to understand these films is to watch them again, from today’s perspective.

Translated from Ukrainian by Anastasiia Mednikova