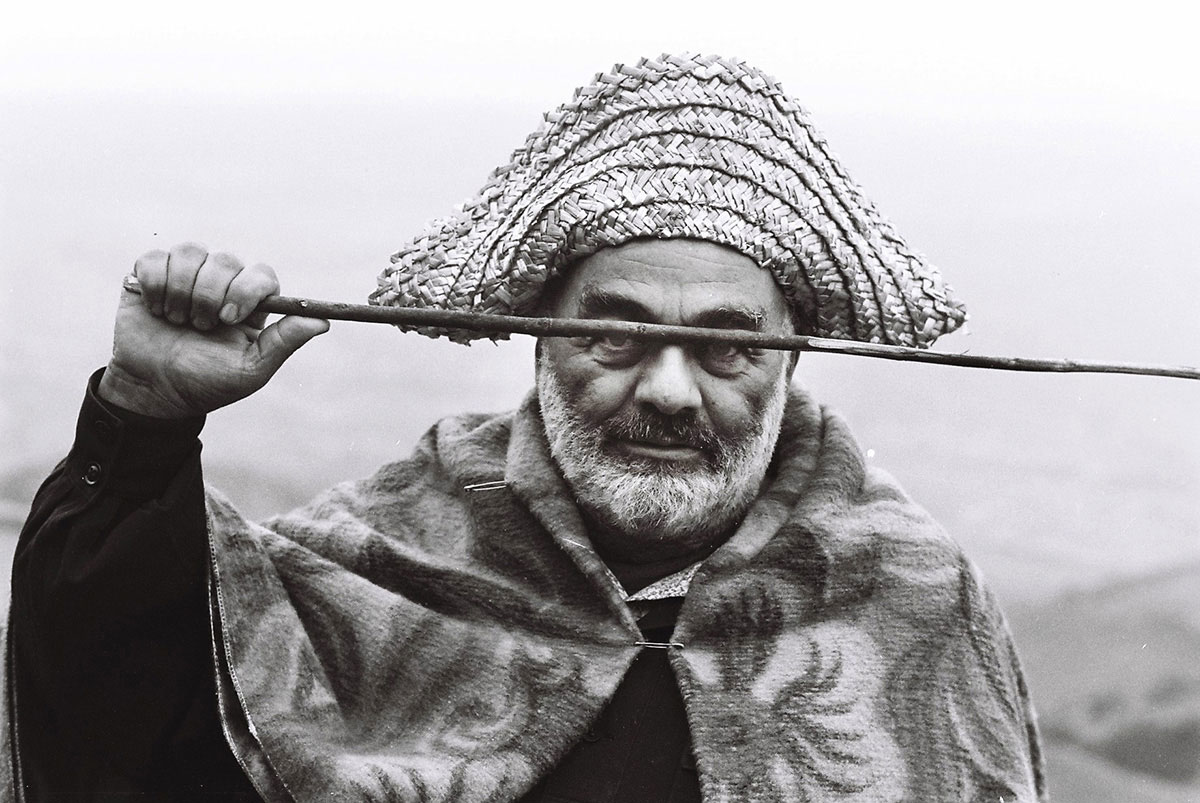

Sergei Parajanov, enfant terrible of Soviet cinema

One striking feature of Sergei Parajanov’s (1924–1990) legacy is that his beautiful films became centerpieces of national film canons in not just one, but three countries, Armenia, Georgia and Ukraine. And they inspired generations of filmmakers across the world. Parajanov himself fully transcended borders and Soviet restrictions — something he paid a high price for in his lifetime. But parts of his personal story and deep impact remain overlooked.

We asked the Ukrainian film scholar Ivan Kozlenko to shed light on them. This piece is a deep dive into one man's life and times.

“I hope you feel that nobody is to able humiliate you in any earthly way and that you are inaccessible and impenetrable under any circumstances, like antimatter?”

The film director Kira Muratova, in a letter to Sergei Parajanov (1970s)

The first attempts to “canonize” Sergei Parajanov in Ukraine occurred during his lifetime. In 1990, the terminally ill film director was awarded the title of People’s Artist of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Perestroika, initiated by Communist Party leaders, was in full swing, acquiring the features of a social revolution by 1988. While the party was losing its authority at a catastrophic pace, its functionaries struggled to hold on to power and keep the comforts they had been so used to. Exiles were given back their Soviet citizenship, yesterday’s “outcasts” were granted ranks and titles.

Parajanov’s rehabilitation by the Communists who had kept him in a Ukrainian prison for almost five years and the cynical attempt to sculpt a “Soviet” artist out of him are a great illustration both of the complex social processes that occurred in the late 1980s and the nontriviality of his figure.

Over time, in the independence era of Ukraine, some were tempted to reduce Parajanov’s non-conventional profile to dissidence. There were certainly grounds for that: an intimate friendship with the Dziubа spouses, close ties with other Sixtiers, participation in protest rallies. The worldwide success of his film Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964) — a landmark for Ukrainian 20th century cinema — ultimately led the new generation to perceive Parajanov as a conscious fighter for Ukraine’s independence. This perception has little connection to reality and considerably narrows the film director’s biography down to his late Ukrainian period while neglecting a period of no lesser importance, the Georgian one.

The most dramatic and decisive factors that shaped Parajanov as a personality and an artist — his education, his professional journey before Shadows, imprisonment, forced unemployment and also his homosexuality — were expurged from his official Ukrainian biography because they undermined and complicated any national-patriotic attribution.

Though he didn’t speak Ukrainian, Parajanov certainly knew the language. He used some Ukrainian words and phrases in letters and interviews, frequently doing so with an ironic touch, for instance to ridicule the Party establishment. He grasped perfectly the various forms of Ukrainian art, so his understanding of Ukrainian culture was much deeper than his language proficiency.

He did not often speak Georgian, although he spent most of his life in Tbilisi, finishing a Georgian school there and knowing the language better than the Armenian. Parajanov hardly ever used Armenian, only inserting certain words in writing, and he never lived in Armenia, although most film encyclopedias list him as an Armenian film director. Parajanov visited Armenia for the first time in 1966, at the age of forty-two. He is buried at the Komitas Pantheon, in Yerevan, even though the director’s wish was to be buried in Tbilisi, next to his parents.

Parajanov was a native of Tbilisi, and he identified himself as such. When he was born in 1924, Tbilisi’s population was largely made up of Tbilisian Armenians for more than a century. They managed administrations and businesses all around the city, and it was this local, ethnic community — its trading class — to which Parajanov’s family belonged.

“Armenia is a great country with an incredible culture, it is my homeland. (…) I have been completely overwhelmed by the beauty and poetry of my people, as I am an Armenian of a Georgian, Tbilisian bottling. I was born in Tbilisi. I have seen Armenia for the first time.”, Parajanov said in a speech in 1971.

Discovering Ukraine

Parajanov first encountered Ukraine in Moscow. As a student of the All-Russian University of Cinematography, he was enrolled in the class of director Ihor Savchenko who was then completing a typical social-realist piece, Third Strike (1948), at the Kyiv Film Studio. Savchenko, known as a fragile poet and authentic experimenter, lived in Russia for almost all his life. The experience of being away from Ukraine was painful for him, so he made films on Ukrainian topics even in Moscow.

Savchenko’s entire class had their practical training on the film set of his opus magnum, Taras Shevchenko (1951). So, when the young Savchenko died before the film was finished, his students were appointed to complete the film, subject to Stalin’s edits. Parajanov also worked on the film for some time, but this was interrupted for several months, which he spent in a Georgian prison on a charge of “sodomy”. Petitions filed by Savchenko, who even involved Korniy Chukovsky, helped Parajanov get released quickly.

In 1952, Savchenko’s legendary class was allocated among Ukrainian film studios, and Parajanov was assigned to Kyiv. The Kyiv Film Studio of that time was a bizarre colonial construct. The authentic expressionist school of the 1930s Ukrainian cinema had been crushed even before the war. Escaping prosecution, some of its young representatives moved to Russia; others perished in purges or on the frontline. Russian directors Mark Donskoy and Boris Barnet, who had fallen out of favor in Moscow, were sent (actually exiled) to Ukraine and tasked with the majority of those rare productions in the 1940s. An undeclared conflict erupted between them and the few keepers of pre-war Ukrainian cinema who had survived the 1930s, a war in which Ukrainians attempted to sabotage the studio’s policy of Russification. The Ukrainian lobby ultimately prevailed, forcing the Russian directors out of the studio.

Surprisingly, the outsider Parajanov stayed.

After his sophomore film Andriesh (1954) and unimpressive The First Lad (1958) shot in the vein of kolhosp comedies, Parajanov makes three documentaries: Dumka (1957), dedicated to the Ukrainian folk choir chapel; Natalya Uzhviy (1959), about a then famous Ukrainian actress; and The Golden Hands (1960), about Ukraine’s folk artists. Not very interesting image-wise, these pictures are an important testament to Parajanov’s immersion in Ukrainian culture. “When I started working on the film The First Lad, I discovered the Ukrainian village — its overwhelmingly beautiful texture, its poetry,” he later described.

In Dumka and The Golden Hands, Parajanov comes across the universe of traditional Ukrainian crafts, the colors of folk decorative art, the authenticity of singing. “I wanted to render the world of these songs in its full primeval charm. I wanted to render the folk “vision” without museum make-up — to direct all these incredible embroideries, patterns, tiles to a creative source, to fuse them into a single spiritual act.”

While working on The Golden Hands, Parajanov put together a team of overthrown luminaries — a small handful of outstanding filmmakers remaining of the brilliant Ukrainian school of the 1930s. Cinematographer Oleksiy Pankratiev who had shot the masterpieces The Self Seeker (1929) and Bread (1930), editor and educator Hryhoriy Zeldovych and the beaten but amazing survivor of Stalin’s purges, Pavlo Nechesa — the legendary head of film studios in Odesa (1920s) and Kyiv (1930s) during the era of their greatest pre-war flourishing. The film gave Parajanov the opportunity to plunge into the context of a defeated Ukrainian cinema tradition.

With The Golden Hands, Parajanov gets to know folk embroidery, carpet-making, wood carving, Opishnia ceramics and its keepers — the Poshyvailo family; as well as the creative work of Kateryna Bilokur which he would admire his entire life. Through applied arts and crafts, Parajanov de facto reiterates the path of the first avant-garde guides led by Alexandra Exter: from folk art to radical artistic experiments.

Film researchers tend to condemn Parajanov’s early films as mediocre, but he did, in his own way, take part in shaping the poetic style of the Thaw period cinema (although not on the scale of Marlen Khutsiev with his Spring on Zarechnaya Street of 1956). In his The Ukrainian Rhapsody (1961) one can feel now and then Parajanov’s decorative approach as to treating color and mise-en-scène. The film’s prologue with its pliant, color conception already contains the beginnings of what would soon evolve into a unique signature style: the main female character sauntering in a bright-red (!) coat down a courtyard in an unnamed European city (shot in Lviv), past multicolored striped umbrellas of cafés and an exhibition of a street artist’s paintings which simultaneously resemble the works of Pablo Picasso, Hryhoriy Havrylenko and Henri Rousseau. Although considered unremarkable, the film shows evidence of digressing from Soviet tropes and offers a more relaxed plastique.

A Flower on the Stone (1962), which Parajanov was completing after the imprisonment of the director Anatoliy Slisarenko, already exudes a compelling yearning to reveal the nature of movement which would be fully satisfied in the Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors with Yuri Ilyenko’s free-spirited camera.

Shadows

So Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964) was not some kind of “wonder” created by “Parajanov, the Armenian”. The path the director had taken — diving deep into the Ukrainian folk decorative, singing and visual arts — led logically to the Shadows. Parajanov, as a creator of mediocre populist dramas, was entrusted with the film adaptation of Yuriy Kotsiubynsky’s work, with an expectation of failure, of yet another “faded” film which would “confirm” the secondary nature and inferiority of Ukrainian literature, suggested by Soviet narratives.

This approach to distinctively Ukrainian material was part of state policy in cinema. The Stalin era introduced bureaucratic fetishization of ethnographic art, framed by a formula: “national in its form and socialist in its content.” With that, all significant, nationally themed, films in Ukraine were created by invited Russians: Ivan Pyryev shot the first kolhosp comedy The Rich Bride in 1938, Nikolay Ekk — the first color motion picture adaption of May Night in 1939, Mark Donskoy — the first sound adaption of Kotsiubynsky’s At a High Cost in 1957. The calculation was plain: loyal to the regime and having little knowledge of the local context, these directors would not be able to “pull through” the scariest chimera of the whole Soviet propaganda — “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism” — into their films. (Donskoy and Parajanov, however, managed to produce authentic works, with a complex synthesis of Ukrainian cultural tradition, free of colonial perspective and exoticization.)

However, the aspect most valued in the “Shadows” by the Ukrainian critic tradition — a genuine national flair — was soon discarded by Parajanov himself. As early as in 1971, he spoke of the “Shadows” in this manner: “I moved absolutely away from this ethnographic, this strongly colonial film.”

The so-called “flair” of the Shadows was, to him, a tool of intuitive penetration into the cosmogonal abyss of existence. Archaic art became his guiding light to discovering the primary elements of cinematic language, and even more — of art per se.

As if extracting basic elements from the cultural depths, Parajanov combined them, creating a new cinematic reality, an authentic one but far removed from any mundane realism. Parajanov’s path led him towards archaic synthesis of ritual, which all of his films following the Shadows would take. For that reason, Parajanov resorted to reduced myth — fairytales, folk epic and legends — in the Shadows, The Legend of Suram Fortress (1985) and Ashik Kerib (1988). For that reason, he worked so obsessively with ancient texts, Armenian, Azerbaijan and Georgian ones, and with Persian and Armenian medieval miniature. For that reason, collage becomes his main expressive method outside cinema — a technique where a free, intuitive connection of elements reaches the level of complete merging, a pre-rational syncretism.

Starting with the Shadows, in all of Parajanov’s next films, sound and speech exist separately from the imagery, synchronizing only on rare occasions to create the simplest illustration. A pure motion-picture image, one liberated of sound, movement, even depth, becomes his absolute obsession after Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. Having plunged into the most archaic forms of art, Parajanov defeated time and brought forth a myth. This also explains Parajanov’s “eccentricities”: as the carrier of mythological consciousness, he did not discern empirical reality from fib even in everyday life.

On the Margins

All of Parajanov’s filmmaking took place on the peripheries, far from the imperial center. Andriesh, the first film he made at Kyiv Film Studio, is an adaptation of a Moldavian fairy tale. Stepping away from the Soviet focus on Russian actors, he took on as many Moldavian actors and crew members as he could.

Parajanov stuck to this emancipative strategy further on in his cycle of Ukrainian films by bringing in Ukrainian performers. It is surprising that the Shadows doesn’t follow that strategy, as is probably features the biggest number of Russian actors compared to any other Parajanov film. Nevertheless, he shot all his Ukrainian films in Ukrainian, while the majority of Ukrainian directors already preferred Russian as the main film language (with subsequent Ukrainian dubbing for distribution in the western regions of Ukrainian SSR). Moreover, Parajanov refused to do a Russian dubbing of the Shadows, stating that it would damage the film’s authenticity.

The transformation Parajanov experienced in Ukraine is paradoxical. Being an Armenian, he became the most passionate supporter of Ukrainian art, criticizing his Ukrainian colleagues for their lack of knowledge and their neglect of a rich local tradition.

Having grown to be a central figure of the 1960s Kyiv art scene, Parajanov brought together the separated groups of this environment. He had the closest ties with artists beyond cinematography circles: visual artists Hryhoriy Havrylenko and Valerii Lamakh, sculptors Mykola Rapai, Yuliy Sinkevich and Mykhailo Hrytsiuk, writers Ivan Drach and Ivan Dziuba, composer Valentyn Sylvestrov. He also acted as an inter-generation link between young Sixtiers and the first modernists, Ivan Kavaleridze and Mykola Bazhan — the living legends of the Executed Renaissance.

Given Parajanov’s creative method, his films cannot be subjected to imperial appropriation. They have nothing in common with the rationally organized and institutionalized state art that the empire could have made its own.

Parajanov was a tireless creator of the Imaginary, that’s why he constituted a threat to the totalitarian state, which monopolized all production of the Symbolic. The Soviet state film production system was built as a mechanism of communist indoctrination, and using it for any other purpose threatened the regime. That’s exactly why Parajanov was eventually banned from work (all of his attempts to produce films in Ukraine after 1966 failed) and later incarcerated. His otherness had an appeal that torpedoed Soviet mythology from the inside. Parajanov’s protohistoric myth, despite its irreality, was much more realistic than the rationally constructed Soviet myth because it was rooted in things unsaid.

Parajanov was free from the restrictions of national cultures in particular. He was thus capable of penetrating the depths of each culture and taking essentials from there: an archaic rhythm, plastique, palette — spirit. Thanks to this “free-diving” enabled by open-mindedness and the absence of restriction in form, he managed to create works of national art free of any exoticization, which can be common for an alien’s superficial perception. Touching upon the origins of cultures, Parajanov remained a supranational artist. He was, to some extent, a Ukrainian, Georgian, Armenian and Moldavian artist. And at the same time, none of them.

Prison

Following the worldwide success of the Shadows and especially after completing the half-banned Sayat-Nova (which got the name The Color of Pomegranate after re-editing), Parajanov grasped the power and appeal of his art. The realization of his own genius and the joy of revealing the profound meaning of art gave him a feeling of invulnerability and moral rightness.

After the screening of Shadows at the cinema “Ukraine” in 1965 — a screening in Kyiv which turned into a political event, Parajanov would criticize Soviet authorities more frequently. This was grounded less in political views than in a sense of the extreme absurdity of the regime. In 1971, during his meeting with students, he openly called a deputy Minister a “floor polisher” incapable of distinguishing mastic from mystique. Statements such as this one were dangerous during the Brezhnev era and its wiping out of Ukraine’s school of poetic cinema.

Parajanov resorted to antiques trading, an activity prohibited in the USSR. Although this subject is often hushed up in Ukraine for fear of discrediting Parajanov, it doesn’t seem he himself felt any discomfort with it. On the contrary: being the son of a well-known Tbilisi antiquarian, he had learned the tricks of the trade in his childhood. In his own world, Parajanov did not break the law but maintained the natural circulation of beauty. And if the laws criminalized these activities — so much for those laws.

It should be mentioned that while trading the antiques, Parajanov was not a classical dealer. He acted within the mechanics of the gift economy, where there is no system of real equivalents. A three-karat diamond has the same value as a 19th century carpet, a collage created with offhand garbage or a doll made of sackcloth. So Parajanov generously gave away valuables, not demanding anything in exchange. He measured an object’s value not by its cost, but by the level of imagination invested into it. If an object lacked imagination, he would enrich it with a story, imparting a new value to it. That’s how cheap bijouterie transformed into dukes’ rings and medieval necklaces: this was not fraud but a magical transformation of a thing.

Parajanov’s sexuality bore the mark of totality and fluidity, like all of his creative work. Beauty had no gender for him, although a woman would be a muse rather than an object of desire.

Nor did Parajanov deny his homosexuality during his first trial in 1948 or his second one in 1973: it was for him a manifestation of freedom, a ritual game in which gender roles could be juggled freely, as in art. But fearing that a conviction on charges of “homosexualism” might harm his son, the director was forced to shun his nature for the first time. Flung down from the heights of worldwide recognition to a prison cell, he asked his ex-wife: “separate me from him [his son] as if I were a leper.”

Parajanov’s first years in prison were marked by depression; his letters are melancholic, full of reflection and sorrow. Only during the third year of his incarceration do his letters becomes somewhat businesslike in tone. Parajanov takes up art again — drawings, collages; a whole group of “apprentices” gather around him, and he arranges exhibitions for them right in prison. Parajanov even asks his colleagues from film to “fix up” his cellmates who “have revealed an inclination” towards art with a job in cinema or theater, to get some scarce goods, to exchange valuables for clothes. Having achieved a certain standing in prison, the director keeps tight connections with the outer world through a lively correspondence with well-known artists and friends.

Following a plea from Louis Aragon, the French poet and bisexual, Parajanov is finally released from prison. Having been banned from living in Ukraine, he settles down in Tbilisi, in his childhood home. Here he becomes the living patriarch attracting pilgrims from all over the world, including Yves Saint Laurent, Marcello Mastroianni and Tonino Guerra.

Towards the end of his life, tortured by unrealized ideas, Parajanov saw himself as a punished and tamed prophet: “I must perish and not save myself. This is my mission.”

Queer

A taste for eccentricity and clothes considered “exotic” had been on display already in his childhood.

As early as in The First Lad of 1958, a typical socialist realism film in its form, Parajanov resorted to encrypted homoeroticism. Here and there the film’s mandatory shots with young sturdy sportswomen are mingled with bare-chested kolhosp laborers unblushingly taking an outdoor shower. Parajanov basically makes fun of the Soviet kolhosp comedy, diluting the genre’s dogmas.

This approach culminates in a scene where the main character realizes that his love is reciprocated. Climbing upon the hill rising against the blue sky, he cries out his beloved’s name in the ecstasy of joy, and this is the moment we see a locomotive ejecting gray smoke into the sky. To complete the sexual imagery, Parajanov places erect truck crane jibs on the flat wagons.

The Ukrainian Rhapsody was Parajanov’s first attempt to use ornaments as a means of alienating the reality. An ornament, a mirror, a candlestick, a frame, a lace — those are not standalone visual elements yet, but only decorative features, nonetheless already sufficiently accentuated in the future films where they will operate as separate forces.

The film’s first scene features paintings (presumably) created by an openly gay artist of the Lviv Zankovetska Theater, Myron Kypryian, who went through a lot because of his homosexuality. One can only guess how close Parajanov and Kypryian knew each other, but considering that some of the film was shot in Lviv, they most certainly met.

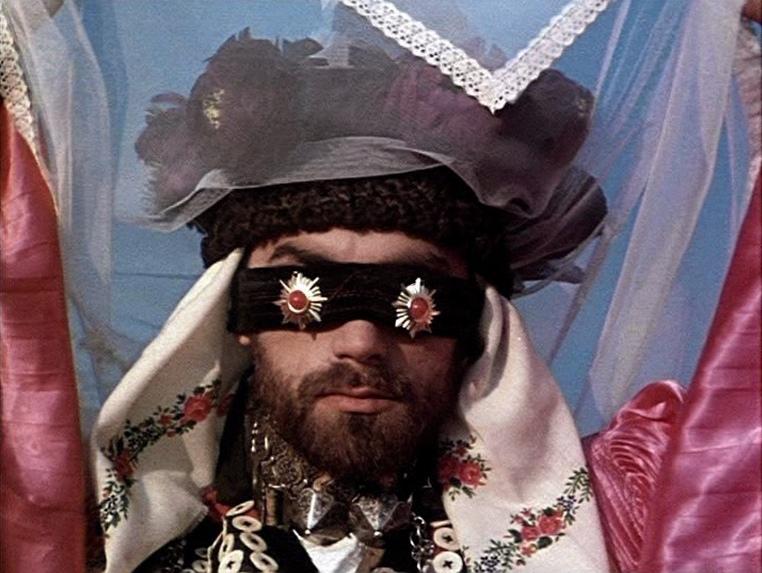

As Parajanov grew to be more conscious of his talent and originality, he started treating gender roles more freely. In Sayat-Nova, the Armenian poet in his young years was portrayed by the Georgian actress Sofiko Chiaureli. She also portrays his bride, as if playing out the act of self-sexualization, identification and gender role blurring.

But in Ashik Kerib (1988), Parajanov’s last completed film, his travesty approach achieves utmost expression. Luxurious outfits, makeup and accessories become the attributes of both female and male characters, with the former paling and trivialized in comparison to the latter. Although the narrative contains a fairly conventional love story between a poor musician and a rich man’s daughter, the main power lines of the plot reveal tensions between male characters. At the beginning of the film, Ashik loses his poor man’s clothes, symbolizing a change not only in his social status but also in a stable gender role which grows uncertain as the plot unravels. Clothes in the film serve as a synonym of presence per se: undressing equals disappearance. The more luxurious clothes, the fuller presence in the world is.

Ashik Kerib was portrayed by a non-professional actor — Yuri Mgoyan, a Kurd from Tbilisi who was Parajanov’s lover. Mgoyan, who was also thrown in a prison a number of times, becomes a kind of “alter ego” for the director, being present in some of the interviews with Parajanov, sitting next to him, wearing magnificent Eastern robes and keeping a meaningful silence, as if embodying “female”, tamed being.

Ukrainian Cinema and Machismo

At the time of Parajanov’s arrest in Kyiv in 1973, according to Roman Balayan’s testimony, Parajanov had been in a long-term, six-year relationship with Oleksandr Vorobyov, a mechanic at one of Kyiv research institutes. The charges of the prosecutor’s office which framed up Parajanov’s case of “abusive buggery” specify Vorobyov as the applicant (victim). As a consequence of the KGB’s pressure and public attention, a tragedy happened: another witness, a twenty-one-year-old architect Mykhailo Senin, son of a Ukrainian Central Committee member, committed suicide after giving his testimony.

Even though Parajanov’s case materials are publicly available (and show that the case was cooked up by intelligence services), the details of the trial against him have aroused interest only in the yellow press since Ukraine’s independence. Documents from the court cases against Parajanov contain important information concerning the history of the 1970s gay community in Kyiv and could shed light on survival strategies in a context of totalitarian rule and the criminalizing of homosexuality. They have, unfortunately, never been researched in earnest within academic LGBT studies.

One of the reasons may be the taboo that surrounds the topic of Parajanov’s homosexuality (and sexuality at large) in Ukraine. Some have denied the director’s homosexuality. And that is not surprising.

The Ukrainian cinematographic community of the 1960s–1980s was extremely patriarchal and sexist. There were just four solo female directors in Ukraine during the entire Soviet period: Yivga Hryhorovych, Vira Stroeva, Sulamif Tsybulnyk and Kira Muratova. A director’s figure was directly associated with masculinity and power.

Renowned directors had no scruples about making public sexist statements — a perfectly Soviet display of machismo.

Homosexuality was harshly repressed in this environment. Parajanov, on the other hand, was ostentatious in his entire behavior. Yuri Ilyenko, a renowned Ukrainian cinematographer, who worked with Parajanov on Shadows, and director, recalled:

“Parajanov approached me from behind and put on an emerald necklace worth 20 thousand rubles on my neck.

— You are the prettiest cameraman I have ever met... — said Parajanov and patted my neck and shoulders...

— Take it off, — I told Serge because I was no longer capable of taking the necklace off myself.

Instead, Parajanov unzipped my jeans”.

This story might have remained a homoerotic anecdote, but haven’t, for its homophobic continuation: “Well, at that moment my left hand lost control and struck Sergik right in the liver.”

Parajanov’s homosexuality is an important key to understanding his imagery and style. All of Parajanov’s “obscene” experiences — prison, antiques trade, homosexual relations — resemble more the rebel path of Jean Genet than that of a Ukrainian dissident patriot. Artist, adventurer, homosexual, convict, but also — prophet and martyr, Parajanov performed the act of transgression in each of those dimensions, and was interested in the political system only to the extent it limited his creative genius.

Even before his arrest was publicly announced, “decent” colleagues from Dovzhenko Studio hastily held a trade union meeting, condemning and denouncing Parajanov. In a matter of months, he was expelled from Soviet Ukraine’s Filmmakers’ Union. Few colleagues had the courage to visit him in prison.

Having reached the depths of myth and ritual, Parajanov ultimately turned his own life into myth as well: “I know that after what happened, my return to art is unfeasible unless I push the boundaries of the possible.”

Translated from Ukrainian by Anastasiia Mednikova