Varvara Khanenko: a life nurturing a museum

The name of Varvara Khanenko was once nearly lost to history, but stands today as a powerful symbol of cultural resilience in Ukraine. Born in 1852 to a philanthropic merchant family, she transformed personal passion into a public legacy, co-founding one of Kyiv’s most significant cultural institutions, the Khanenko Museum. On 10 October 2022, the museum was damaged by a Russian missile. But it survives, just as her legacy endures, and the memory of her life marked by upheaval and war. This article traces the remarkable journey of a woman whose spirit continues to inspire.

“She did not want to leave Kyiv and the museum, which was more precious to her than her life itself.”

Serhii Hiliarov

The short list of people who created the institutional framework of Ukraine’s early 20th century cultural heritage includes a woman’s name: Varvara Khanenko. A collector, philanthropist, patron of the arts, and founder of the Khanenko museum in Kyiv, Varvara was born in 1852 in Hlukhiv, in today’s Sumy region of north-eastern Ukraine. She was the eldest of six children in a family of wealthy merchants, Nykola and Pelaheya Tereshchenko.

We know little about Varvara’s childhood and youth. “She was educated at home, brought up in the good traditions of piety”, wrote Vitalii Kovalynskyi, a biographer of the Tereshchenko family. Varvara spoke French and English, as is evident from her letters to her family, preserved in the Kyiv archives. These letters offer a glimpse into the early years of her life. Filled with heartfelt care and tender affection. With all the diminutives, “Oliushky,” “my Oliunechka,” “our mamulechka,” “auntie,” “uncle,” “Bohdasha,” “Basia”, and generously sprinkled with warm hugs, low bows, and strong kisses, they reflect a family happiness, love and affection that, I believe, Varvara experienced from childhood.

The history of the Tereshchenko family reveals the key context that formed her personality. When she was born, her thirty-two-year-old father Nykola Tereshchenko was already Hlukhiv’s most successful entrepreneur and a generous philanthropist, serving as mayor. Her mother, Pelaheya, was also actively involved in charity work. Varvara grew up among energetic, capable people who were rising in wealth, status and worldview. In 1870, the year Varvara turned eighteen, the Tereshchenko family was granted a noble title and a coat of arms for their charitable services, choosing as their motto: “Striving for the public good.”

Merchant-like, pious and sentimental, nouveau riche and pragmatic — the Tereshchenkos were drivers of change in their environment. Their move to Kyiv in 1875 marked the beginning of a new era in the city’s history. A modern, socially and culturally developed Kyiv was emerging, fueled by the immense profits drawn from sugar production. How could Varvara not be influenced by this spirit of active, productive, outward-looking life? I’m convinced that the Tereshchenkos’ worldview and character acted as a leaven in the maturation of their philanthropic projects and their magnum opus, a museum of world art.

Sometime in the early 1870s, in one of the imperial metropolises, the young Varvara Tereshchenko met a young, educated nobleman, Bohdan Khanenko, a passionate art lover. They married in July 1874 and immediately set off on a trip to Europe. Bohdan later recalled in his Notes: “I got married and traveled abroad with my wife; on the way, we visited the art galleries and museums of Vienna, Venice, Bologna, Florence, Rome, and Naples, (...) the days were happy, full of smiles, and we bought what we liked; by the way, understanding very little about painting at the time, we, however, didn’t make a mistake and bought quite decent paintings”. That wedding trip marked the beginning of the Khanenko collection.

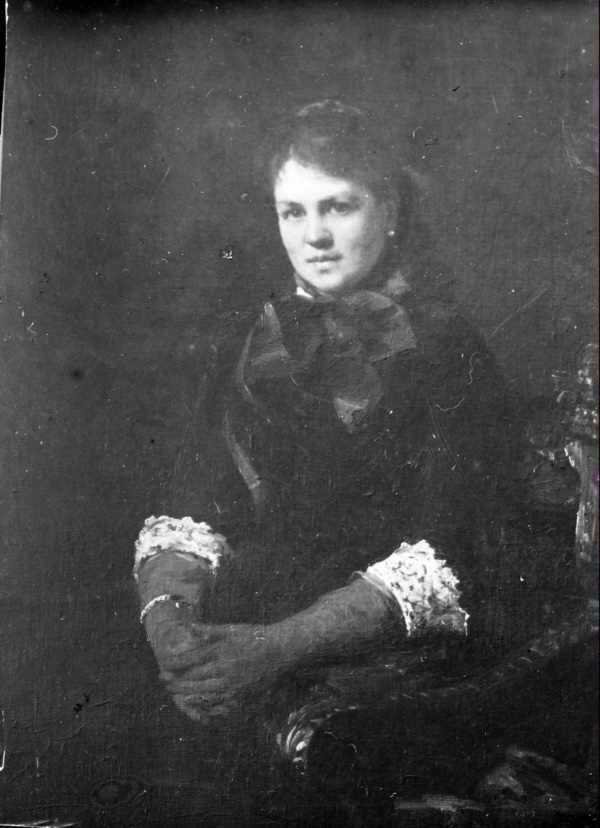

After completing his service in the judiciary in St. Petersburg and Warsaw, Bohdan retired in 1881. Varvara was about to turn thirty, but they had no children. Young, free, and hungry for knowledge, the Khanenkos led the lives of new European nomads: traveling across European cities, learning up close about the history of western culture and the art of eastern countries. They bought and sold works of art, intoxicated by the thrill of treasure hunting and drawn to the secrets of ancient masters. In 1885, the Roman artist Ulpiano Checa painted 33 year-old Varvara Khanenko: beautiful and full of joie de vivre. An old photograph of their home shows this portrait standing on an easel near Bohdan’s desk.

In the late 1880s, Nykola Tereshchenko encouraged the Khanenkos to settle next to him in Kyiv, even finding them a good plot of land opposite the university. Bohdan and Varvara accepted: their already considerable collection needed a home. They envisioned their house as an architectural homage to the great tradition of Europe, filling it with visual references to Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, and Art Nouveau styles. The sophisticated aestheticism of the main rooms on the first two floors contrasted with the simplicity of the living quarters on the third, mezzanine floor: two rooms, a bathroom, and a corridor, with one door leading to a narrow balcony under the ceiling, where books were kept in built-in wall cabinets.

The Khanenko house bore witness — and still does— to the inseparability of Varvara’s story from Bohdan’s. An energetic and charismatic intellectual, public figure, collector, organizer of archaeological research, and compiler and publisher of art books, Bohdan Khanenko became the head of the Tereshchenko sugar syndicate in 1896, while also leading the Kyiv Society of Antiquities and Arts. He was the only person who managed to break through the empire’s deadlock and obtain permission to open the first public museum in Kyiv — the Museum of Ukrainian History and Culture. Bohdan Khanenko concluded his keynote speech at the museum’s inauguration with an unexpectedly personal statement: “Not only the prosperity of a public institution, but also (...) the life of any creature in our world is unthinkable without love, without the love that binds, gives strength and faith in work, and ensures its success”. Why, speaking about the role of the museum, did he emphasize love as the fundamental basis of everything? What else but if his personal experience, his marriage to Varvara, could have prompted Bohdan to share those thoughts and words?

Varvara’s letters from that highly productive period for both Khanenkos — at the turn of the century nineteenth — reveal a private yet significant dimension of their lives: Bohdan’s chronic respiratory illness, with its sudden attacks, kept Varvara in a state of constant anxious vigilance, always ready to put everything aside to care for her beloved.

And she truly did have much to set aside. The image of Varvara as merely Bohdan’s “faithful companion” and “zealous assistant,” created in the 1990s, began to change as her letters were read in archives. As it turned out, Varvara was an avid collector with her own interests, separate from her husband’s, and with her own “sections” of the collection. “I have a passion for collecting, and it is a terrible pity to miss a really good thing,” she wrote to Ilia Ostroukhov, an expert on ancient icons. Icon painting, Italian majolica, Ukrainian folk art — it seems Varvara was drawn to man-made nature, emotionality, and the profound spiritual “simplicity” of these diverse art forms. “I (...) feel their beauty and get real pleasure from looking at them (...), it is a revelation for me,” she wrote about icons. Varvara also took a deep interest in the scientific study and restoration of icons, corresponding with historian Nikolay Likhachev and art historian Nikolay Chernohubov on the subject.

Ukrainian folk art was her second passion. Even in early discussions about Kyiv’s first museum, Varvara sympathized with the pro-Ukrainian concept proposed by historian Mykola Biliashivskyi, who would become the museum’s director. Later, she began personally collecting traditional Ukrainian clothing, carpets, and ceramics. In one of her letters to Bilyashivskyi, she wrote: “So (...) a favor for a favor: I help you buy the Mezhyhiria collection, and you please make me a diverse collection. You said that you have some interesting duplicates in your museum, and I am especially interested in lace and white embroidery.” Varvara Khanenko’s passion was generous in the Tereshchenko way: between 1899 and 1909, she donated about 1,200 examples of folk embroidery, 150 pieces of ceramics and blown glass, and ten carpets to the ethnographic department of Kyiv’s first museum.

In 1904, Varvara organized a school and a workshop for traditional Ukrainian weaving and embroidery at her estate in Olenivka, in the Kyiv region. She sent the school’s students to study the finest examples of folk art at the Biliashivskyi museum and provided the highest quality looms and threads for their work. In one of her letters, Varvara asks Vikentii Khvoika, an expert in Ukrainian traditional culture, to find an experienced carpet weaver who would teach her traditional weaving techniques. In 1905–1906, she became actively involved in organizing the museum’s first handicraft exhibition, and in establishing the Kyiv Handicraft Society. Among the Society’s founders, alongside Khanenko and Biliashivskyi, were Kost Moshchenko, Olena Pchilka, Danylo Shcherbakivskyi, Nataliia Yashvil, Nataliia Davydova, and Vikentii Khvoika. Varvara also invited the artist Vasyl Krychevskyi to teach folk coloring and ornamentation at Olenivka and to develop sketches for new products. A carpet based on Krychevskyi’s design later received a silver medal at the All-Russian Industrial and Agricultural Exhibition in 1913. Inspired by this success, Varvara opened a shop in London selling Ukrainian handicrafts).

Her activities were not limited to her estate in Olenivka. For years, Varvara supported the village amateur theater in Mohylne, in the Podillia region: she hired a director, created costumes, organized meetings of the troupe with Mykola Sadovskyi and Marko Kropyvnytskyi, and arranged tours. She also opened a pharmacy and an outpatient clinic in Mohylne. In Rayhorodok and the Cherkasy region, she established a two-class school. Year after year, schools, hospitals, orphanages, and churches were built on the Khanenko estates; streets were paved and lit, and agricultural innovations were introduced. Varvara personally oversaw the cultivation of new varieties of fruit, improved seed quality, and tended her rose gardens. This extremely active and fruitful life was first interrupted by World War I — and ended entirely in 1917.

Bohdan passed away in May 1917. In his will, he asked his wife to organize their collection and open a Museum of World Art in their house on Tereshchenkivska Street. The chaos following the Bolshevik coup in Petrograd pushed Varvara to take a bold risk: in December of that year, she transported part of their collection from Petrograd to Kyiv. Among the rescued items were a coronet with an archangel by a 15th century Umbrian master, the Portrait of a Patrician attributed to Gentile Bellini, 16th century Umbrian and Venetian Madonnas, Orpheus and Eurydice by Jacopo del Sellaio, the Portrait of the Infanta Margarita (then believed to be a work by Velázquez), a still life by Juan de Zurbarán, Chinese sculpture from the 7th to 10th centuries, and a 15th century Persian miniature. In January 1918, Russian Bolsheviks under Muraviyov’s leadership ravaged Kyiv, destroying and looting the city. Unique art and antiquities collections belonging to Mykhailo Hrushevskyi and Vasyl Krychevskyi were destroyed in the fires. Pavlo Skoropadskyi came to power in the spring with the support of German troops. The Germans, sensing the situation, offered Varvara the chance to safely transport the collection to Germany. Despite her fear, she refused: the Khanenko Museum was to be founded in Kyiv.

On December 15, 1918, anticipating further social upheaval, Varvara Khanenko submitted a statement to the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, donating her art collection, book collection, and house. She set some conditions: the museum should bear the names of its founders, the collection should not be divided, moved, nor supplemented, and an Institute of Art History should eventually be established at the museum. But by February 1919, Kyiv fell again under Bolshevik control. The private collections were nationalized, and the Khanenko house was swiftly converted into a museum. Varvara accepted this reality. She found Heorhii Lukomskyi, an art historian experienced in transforming private collections into public museums, and together they began their work. In May 1919, the museum welcomed its first visitors.

We learn much about this peak period in Varvara’s life from Heorhii Lukomskyi’s fictionalized memoirs, which he published several years later while in exile. Despite their occasional “curatorial” disputes, the 35 year-old Lukomskyi sincerely admired the 66 year-old Varvara Khanenko. He recalled their first meeting: “We went around the collection and got acquainted with it in detail, together with V.N. [Varvara Nikolayevna – ed.]. I admired and marveled at her energy, her ability to purchase, her dexterity, her constant and unrelenting interest, even her passion for art. She would show me her favorite pieces, tell me about where, when, and under what circumstances they were acquired, and her stories cried out to be written down! How I regret now that I didn’t record all these details and explanations at the time.”

The Bolsheviks assigned a “political leader” to oversee the museum’s organization. In April 1919, Valentyn Rozhytsyn moved into the Khanenko home with his wife and children and immediately decided to evict Varvara to a small room. However, Kyiv’s cultural came to Varvara Khanenko’s defense, safeguarding her dignity and rights, and Rozhytsyn was eventually removed from the museum. There were other humiliations as well. Lukomskyi recalls that Varvara was later forbidden from entering the museum halls so as not to “cause surprise as to how the owner herself lives in a folk museum.” It is from Lukomskyi’s memoirs that the popular Kyiv legend “about the dog” emerged: Varvara, defying the ban, “sometimes came with her dog, secretly taking the storage keys.”

In the fall of 1919, with the next change of power in Kyiv, Lukomskyi fled abroad. He urged the elderly Varvara to join him, but she refused. Serhii Hiliarov, an eyewitness to the events — an art historian and museum worker — would later explain: “She did not want to leave Kyiv and the museum, which was more precious to her than life itself.”

It was only in the summer of 1920 that the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences finally took the Khanenko Museum of Art under its protection. The museum committee included the most authoritative experts of the time: academicians Fedir Shmit, Oleksii Novytskyi, Mykola Biliashivskyi, Mykola Vasylenko, and the professor Mykhailo Boichuk. Varvara Khanenko was appointed an honorary member. At her suggestion, the professor Mykola Makarenko became the museum’s director. In this way, she fulfilled her mission.

Varvara Khanenko died in her home on Tereshchenkivska (then Chudnovskoho) Street on May 7, 1922. Two weeks later, Makarenko reported that the entire Khanenko business archive and private papers had “disappeared somewhere.” In 1924, “in view of the complete absence of Khanenko’s revolutionary merits related in any way to the service of proletarian culture,” the names of Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko were removed from the museum’s name. In 1925, entire sections of the collection started being transferred to other museums, while other, anonymous collections were brought in to replace them. Only photographs remained of Varvara’s portraits. The Soviet machine of erasure worked efficiently: by the mid-1980s, almost no one in Kyiv remembered the Khanenko name. In 1986, the Museum of Western and Oriental Art underwent a major renovation — and was stripped of that memory.

The museum started coming back to life in the second half of the 1990s — this time, once again, as the Khanenko Museum. Archival research made it possible to scientifically reconstruct the house and restore its historical name. The museum on Tereshchenkivska Street became a center of Khanenko studies, though at first, these studies were noticeably focused on Bohdan. It was not until 2013 that the first inter-museum exhibition dedicated to Varvara Khanenko, The Meaning of Her Life, finally opened. For the first time in ninety years, Varvara’s Ukrainian artifacts — scattered across various Kyiv museums — returned to the Khanenko house, if only temporarily: icons, embroidery, porcelain, carpets. And together with these objects, together with the letters that had been read and the memories of her contemporaries, and other fragments of the past that had been recovered — she herself returned. Her active and fruitful life, her quiet fortitude, and her loyalty to the museum were brought back to us.

Yet can we truly say that we’ve understood the meaning of Varvara Khanenko’s life? That we have grasped her motives, her impulses, her loves? Or are we, perhaps, encountering only a shadow — a silhouette shaped by the gaps and voids of memory, filled with our own projections, our own longing for her, Varvara, just as she once was?

These reflections around the research were abruptly and painfully reshaped by war. When the Khanenko mansion was damaged by a Russian missile on October 10, 2022, Ukrainians experienced a horror eerily comparable to the terror Varvara Khanenko had felt in early 1918 — when, holding her breath, she listened to the dreadful explosions in Pankivshchyna, just a few blocks from Tereshchenkivska Street, and soon learned of the destruction of priceless art collections. Could she have imagined then that, a century later, in the same house — now a museum — completely different people would once again sit in terror, and that their resilience would be sustained by thoughts about her, by memories of her, in loyalty to what she had built?

The fact that the Khanenko Museum in Kyiv survived 20th century the cataclysms, and that now — in the face of a genocidal Russian war — it remains a stronghold of Ukrainian culture, is in no small part thanks to Varvara Khanenko’s personal, enduring contribution. Let us remember this.

Translated from Ukrainian by Yulia Kulish.