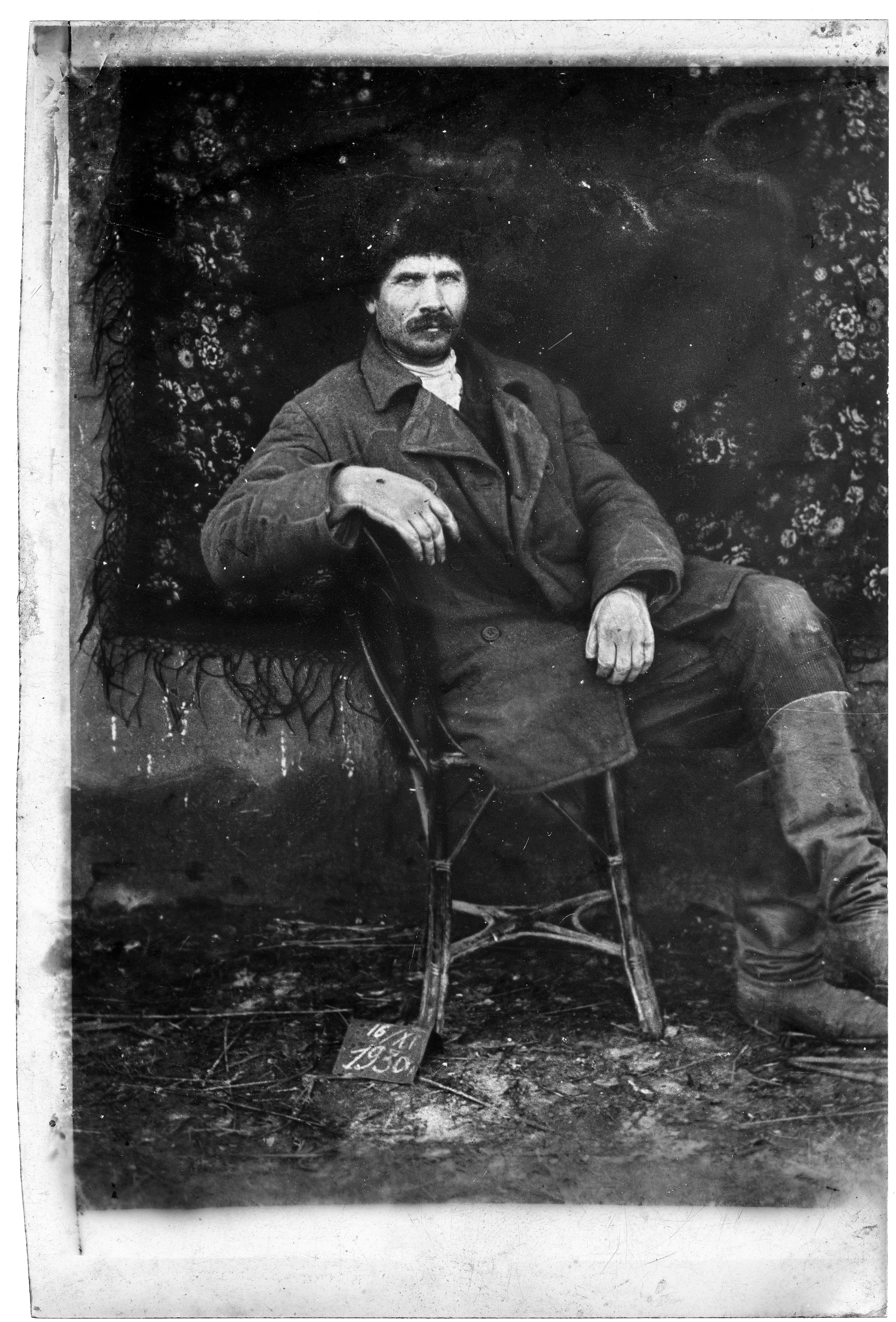

Ukrainian photographer Marko Zalizniak’s 1930s self-portrait

Even in its preserved fragment, the glass negative shows the portrait of a man taken on 16 November 1930 — nearly a century ago. The composition is characteristic of portrait photography from the late 19th to early 20th century.

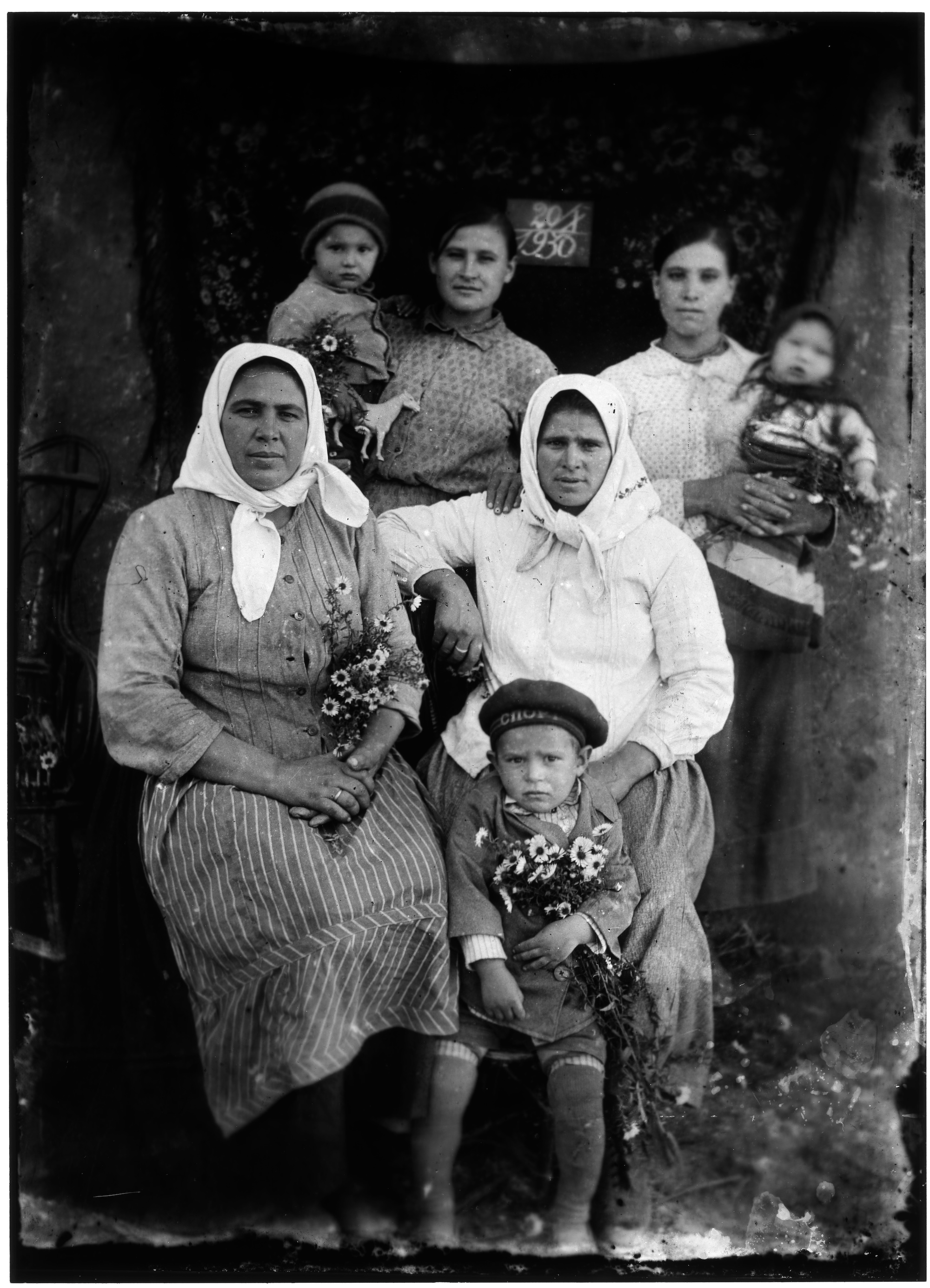

At the time, having one’s portrait taken was a kind of ritual. A visit to the studio required careful preparation, as the image was expected to convey not just personal appearance but also social class, family ties, and the hierarchy among those being photographed. Painted backdrops were commonly used in studio portraits, often depicting romantic landscapes with architectural elements. Props such as chairs, stands, imitation columns and flower pots were frequently arranged around those posing. Curiously, while studio photographers attempted to mimic natural scenery in their backdrops, outdoor photographers often did the opposite — trying to hide real landscapes with fabric screens or improvised materials. This photograph offers a glimpse into that very practice.

The photograph was taken by Marko Zalizniak near his home in the village of Romanivka, in the Donetsk region.

Marko Zalizniak worked as a photographer during the first half of the 20th century and is best known for his documentation of Soviet collectivisation and the Holodomor famine. He served in the army during both world wars and later worked as a labourer. As a photographer, he also took part in an archaeological expedition along the Dnipro river prior to the construction of the Dnipro hydroelectric power plant. In addition to his widely recognised photographs — which have long been valuable sources for historians — Zalizniak also captured images of his family, neighbours, and everyday rural life. This personal collection is now kept in the Urban Media Archive of the Lviv Center for Urban History, thanks to the efforts of his grandson, Volodymyr Havshchuk, who was determined to make sure the family archive wouldn’t fall into oblivion, as so often befalls such documents.

According to Volodymyr Havshchuk’s recollections, villagers often visited his grandfather to have their portraits taken, typically paying him with their farm produce. One such portrait in the family archive depicts a group of women with children, photographed in an improvised ‘studio’ set up against the wall of the house, where the natural light was most favourable. A headscarf — the darkest element in the frame — hung in the background to shade their faces and figures, while a lighter, floral-patterned cloth framed them. Straw scattered on the ground added texture and helped balance the composition, especially around the detail-rich area near the faces. It’s evident that the photographer was experimenting with focus: the seam where the wall meets the ground, along with background elements, appears blurred. The women and children sit comfortably at the centre of the frame. Their slightly dishevelled clothing — a jacket with a missing button at the chest, simple flowers loosely held like a child holding a toy horse — conveys a relaxed, informal attitude toward the camera. These are people who know their neighbour well and feel at ease in front of his lens. The photographer’s authority is more a matter of theoretical discourse than something that shaped their lived experience.

Zalizniak’s self-portrait can be linked to the image of the women with children through several recurring visual elements: a floral scarf in the background, a chair, a straw-covered floor, and a plaque with dates written in the same distinctive handwriting. Yet despite these shared details, the two photographs differ strikingly in their composition and in the posture and presence of their subjects.

In the man’s portrait, the frame is slightly shifted to the right, cropping both his feet and part of the background scarf. The subject is the photographer himself, Marko Zalizniak. Using the camera’s automatic shutter release, he sits confidently on a chair, his wrinkled clothes and relaxed posture suggesting a natural ease in front of the lens. This is a self-portrait, and the slight misalignment of the composition only reinforces that impression. It’s likely that Zalizniak had just been photographing others and didn’t adjust the setup to suit his own position — resulting in part of his body falling outside the frame.

When the photo was taken on 16 November 1930, Zalizniak was working at the time with glass plates coated in a light-sensitive emulsion. Before the digital era, analogue photography typically followed a two-step process: first, the photographer captured a negative on a light-sensitive surface; then, the image was printed onto paper to produce a positive photograph that could be shared with clients. This approach enabled multiple reproductions of the same image, as well as the possibility of enlargements, retouching, and collage work. The development of this two-step method was made possible by the introduction of transparent film, which became the standard base for negatives. Prior to the invention of film, however, glass served as the primary transparent medium — though it was fragile, and required painstaking preparation, as well as careful handling and storage.

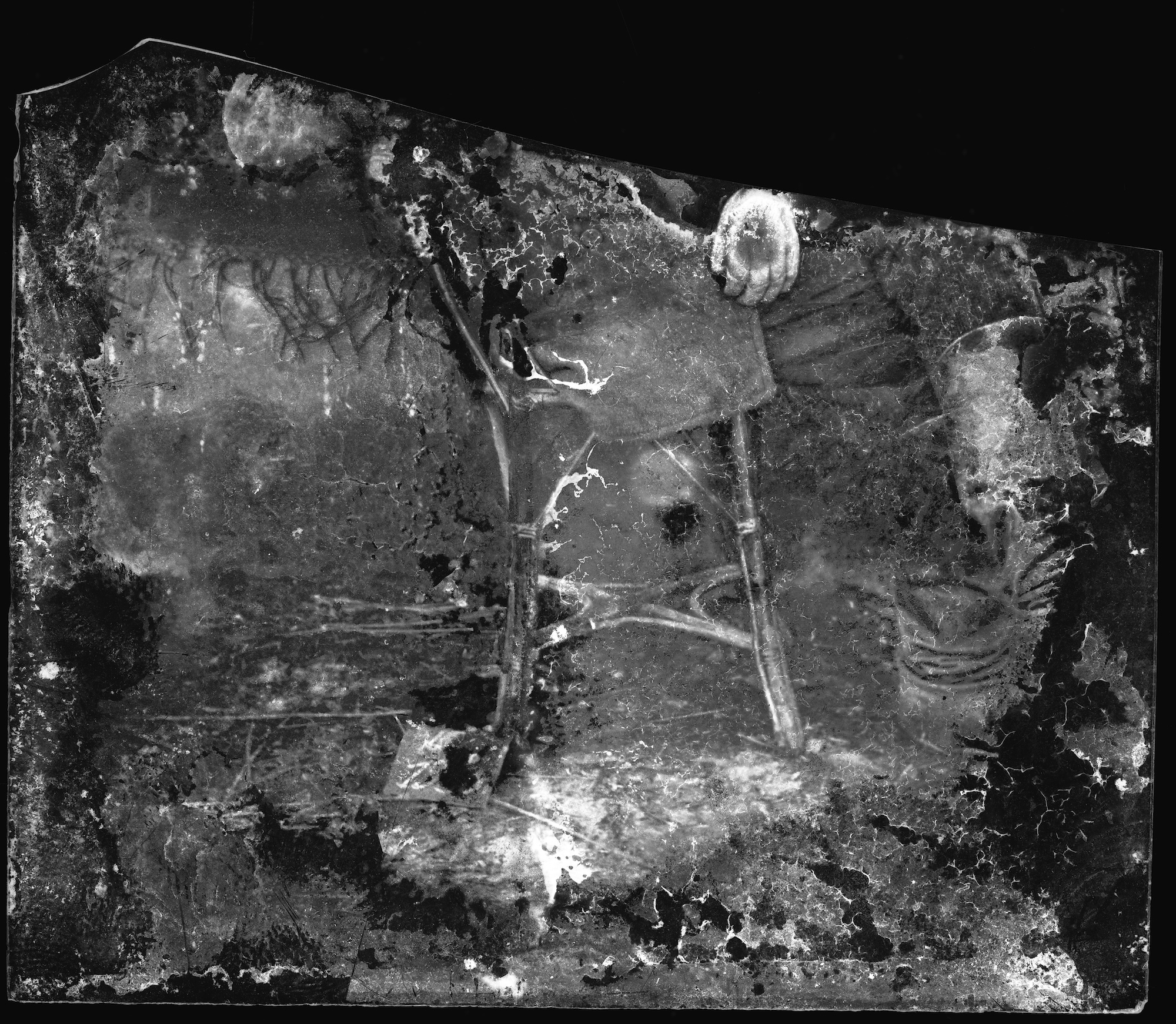

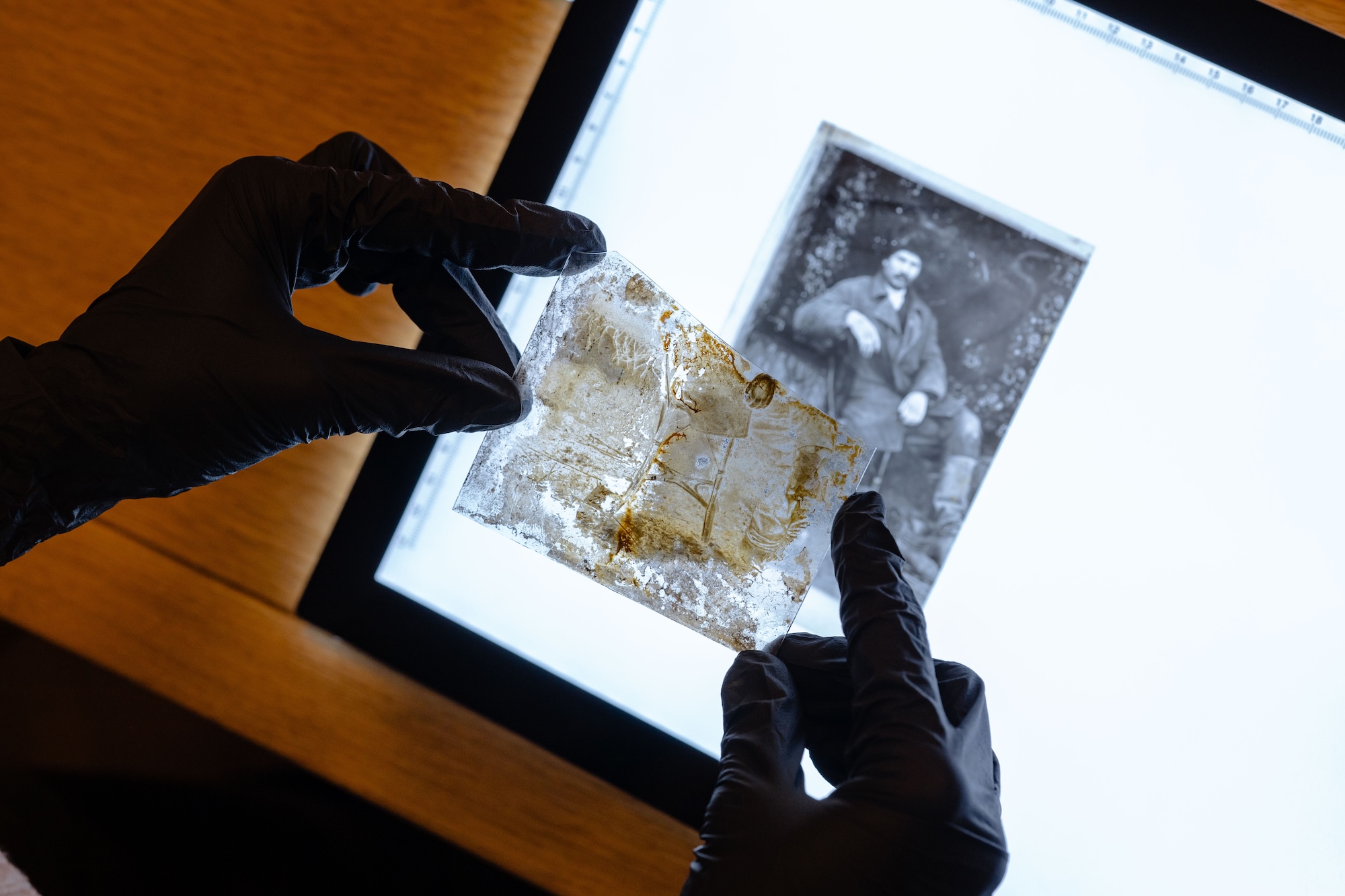

Glass negatives not only preserved images but also bore visible traces of time and environmental exposure. In this case, the emulsion has flaked away in large sections along the edges of the plate, erasing parts of the image. Fine cracks stretch across the surface, becoming part of the photograph’s very texture. This example vividly demonstrates the intimate bond between an image and its material medium — a connection that only deepens with the passage of time. Fortunately, before the glass negative broke and part of the portrait was lost, Zalizniak made a copy. Using a traditional analogue method, he placed the glass negative over a sheet of film and exposed it to light. After developing and fixing the image in a chemical solution, he produced a positive on film.

This act of preservation was deliberate and thoughtful: Zalizniak clearly understood the fragility of glass and the comparative durability of film. Yet even when the copy was made, the glass plate was already damaged — scratches on the negative were transferred to the film, becoming part of the new image. Over the next seventy years, the film itself accumulated its own traces of time passing by — scratches and marks now form part of this second-generation version of the portrait. Three years ago, we digitised the collection at the Centre for Urban History, creating digital versions that are fundamentally different in nature — ones that will, in turn, be subject to their own forms of transformation and vulnerability over time.

Translated from Ukrainian by Yuliia Kulish.