Cecilia Klaften (1881-1942): Working for a better tomorrow

Cecilia Klaften was a pioneering educator who transformed Jewish girls’ education in interwar Lviv. Trained in biology, she turned to social work after World War I, founding a vocational school that empowered young women to build independent lives. Her work gained international recognition. Yet her story cannot be read without its tragic end during the Holocaust. This essay traces the extraordinary legacy of a woman who fought for dignity in the face of adversity.

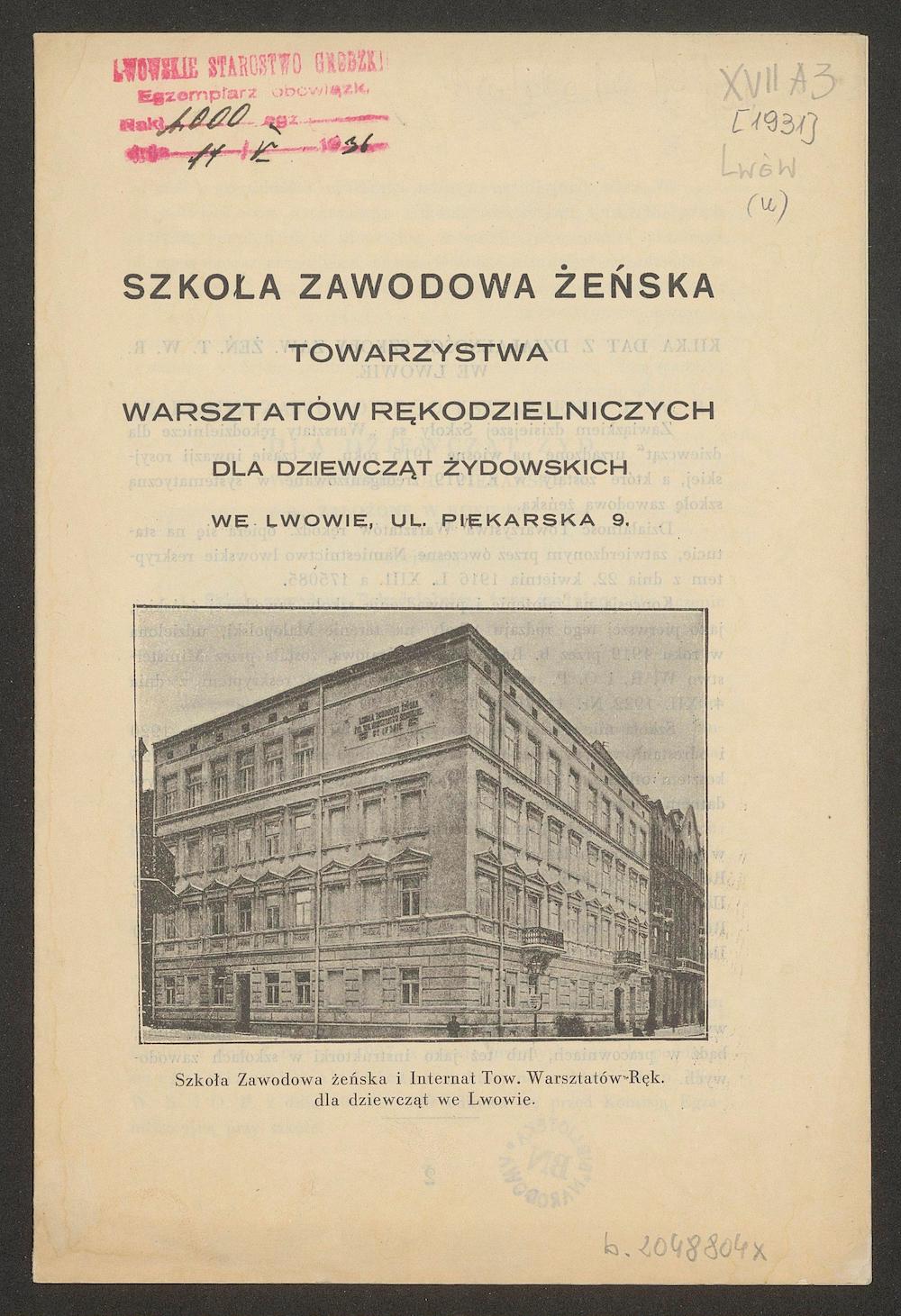

What used to be the Cecilia Klaften Vocational school for Jewish girls is just across the street from my office. I’ve passed by many times on my way to get coffee – the building is now home to the workshops of the Technical School of Light Industry – but only when I began researching Klaften’s biography did I start to look up. Two occupations and a Holocaust have erased from this Lviv facade the name of one of the city’s most remarkable figures, the author of a transformative initiative to provide vocational education to Jewish youth.

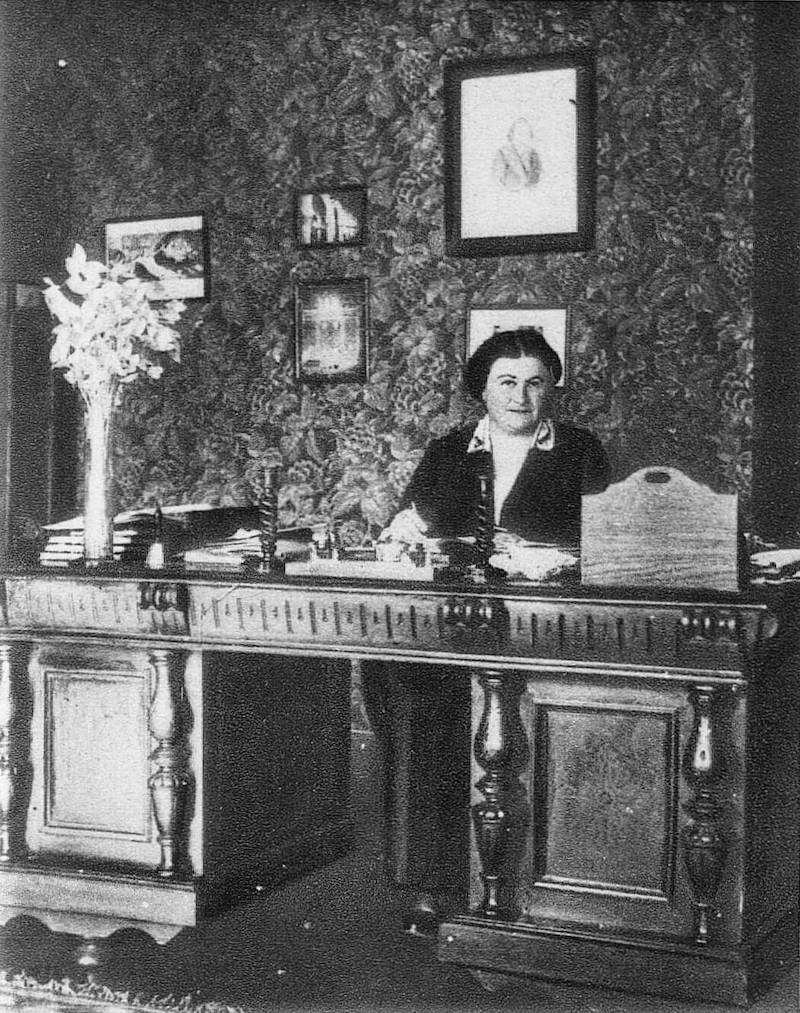

Cecilia Klaften managed to embody several eras in a single life. Born and educated in Habsburg Galicia, she was part of a generation of women who benefited from a double emancipation allowing her to pursue what had been unthinkable for previous generations of Jewish women: a university education in biology.

Her coming of age coincided with a period of rapid upheaval in interwar Poland. The devastation of World War I forced Klaften to transition from a career in biology to public service and youth education. Her erudition, ambition, and talent for leadership soon propelled her to prominence in the field of Jewish education. Yet, after 1939, everything she had built – her projects, her schools, her vision – was shattered, first by the Soviet and then by the Nazi occupation.

Born Cecilia Beigel, she arrived in Lviv from Ternopil in 1896 as a fifteen-year-old preparing to pass her final exams. She supported herself by giving private lessons. The Lviv of the late 19th century was at the peak of its economic growth; a city of rapidly expanding infrastructure. The changes were visible in the tall Art Nouveau buildings going up in new neighborhoods, the electric tram that had started rattling up and down the streets two years before her arrival, annoying locals to no end, and the elegant modern cafés. The city felt like an engine gathering speed.

Where did a young Jewish woman from the provinces fit into this environment? She was unlikely to identify with the Jewish business elite who owned the new apartment buildings, nor is she likely to have felt at home in the old Jewish quarters of the Zhovkva suburbs, where modernization was slow and poverty entrenched.

Cecilia’s path in science began with a doctorate in biology from Jan Kazimierz University, followed by work as a laboratory assistant and researcher at the Institute of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy under professor Józef Nusbaum-Hilarowicz. For a time, she was a colleague of the renowned biologist Rudolf Weigl. But her academic work paid poorly, and to make ends meet she also taught at the Lviv School of Commerce and in a private gymnasium.

Before the war, she married engineer Alexander Klaften, who died soon afterward. She kept his surname – Polish newspapers referred to her as “Dr. Klaftenowa” – but she never remarried.

World War I changed everything: in Galicia, and in Cecilia’s life. In 1914, Lviv fell under Russian occupation and waves of refugees – many of them Jewish – flooded the city. At thirty-three, Cecilia shifted her career from science to social work. Seeing the needs of young women, she organized sewing workshops, securing sewing machines through charitable donors.

After the war, this experience shaped her conviction that Jewish society, particularly its youth, needed more systemic support. Postwar Lviv found itself in a new state — the Second Polish Republic — having lived through World War I, Russian occupation, the Polish-Ukrainian war, and antisemitic pogroms. The pogrom had revealed the precarity of the Jewish community’s position in the city: its efforts to stay neutral during the Polish-Ukrainian conflict had led to accusations of treason. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the community had to battle growing hostility from nationalist circles and later the state itself, economic hardship, restrictions on their education, and boycotts. Jewish youth, scarred by war and splintered among competing ideological movements – Zionist, leftist, and ultra-Orthodox – struggled to find their place in the new state.

It was in helping to ease this struggle that Klaften found her niche. She poured her energy into a vocational school for Jewish girls, located in a large building at 9 Pekarska Street in central Lviv. The school offered two- and three-year courses in tailoring, lingerie making, and embroidery. Along with these technical subjects, students studied Jewish religion and Hebrew, Polish and foreign languages, history, hygiene, chemistry (taught by Klaften herself), economic geography, civics, singing, and gymnastics. Some programs prepared students for the journeyman’s exam required to open their own workshops, while shorter courses taught home economics. In 1927, 369 young women were enrolled.

Klaften strove for the highest standards. Distinguished teachers were invited to lecture; students’ works were exhibited in Vienna and Paris. Some of these works sought to revive traditional Jewish craft, such as the embroidered parochets (Torah ark curtains) for synagogues. The building itself was redesigned in the Art Deco style, and in accordance with the latest sanitation practices, by modernist architect Józef Awin.

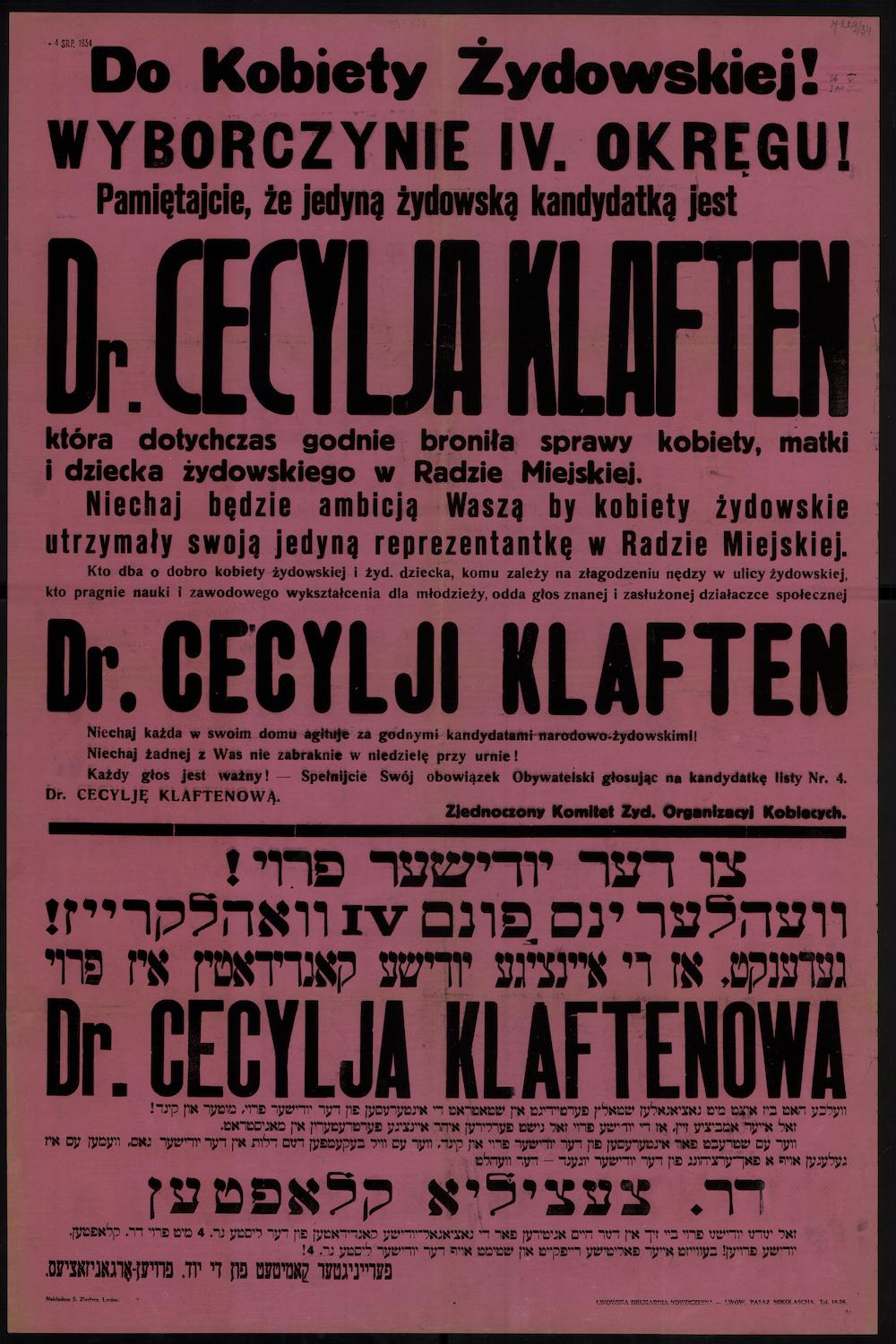

Klaften’s voice could often be found in Polish and Yiddish newspapers, election campaigns, and appeals to charities. One word she used frequently was “productivization,” which summed up her concept of societal progress.

Jewish activists had internalized the critique of commerce as “unproductive labor” and were trying to encourage Jews to transition into crafts, agriculture, and industry. The movement for “productive” labor among Jewish youth emerged in response to antisemitic tropes about Jews being overrepresented in trade. Klaften and her contemporaries envisioned change happening through professional education and scholarships to help young men and women launch their careers.

Agriculture was seen as one of these “productive” occupations. Thus, Klaften initiated the reopening of a prewar agricultural school in Slobidka Lisna, a small village near Kolomyia.

In 1936, she wrote in the newspaper Opinia: “The deeply rooted idea of productivization will bear fruit only when young workers no longer lack bread, shelter, or clothing – when their choice of profession is deliberate, when they can enjoy the benefits of their education and see it through to completion. In order that their energies are not wasted, not spent on nothing, that they may fight for a better tomorrow – we must organize an aid campaign for the youth and make it real.”

This vision of the future reflected her belief that activism and grassroots initiatives could raise a generation of Jews who would find their rightful place in society.

In one of her interviews, Cecilia Klaften stated that debates about women’s emancipation or the right to vote seemed overly theoretical compared to the urgent need to help women find work. During her visits to Palestine and America, she was inspired by women who worked alongside men as equals in kibbutzim, drove cars, or worked in offices. Those were the kinds of women she wanted her schools to turn out: women who could find work they loved and turn it into a livelihood.

Dispatches and news articles from the 1930s describe Cecilia Klaften as one of the most widely admired and best-loved public figures in Lesser Poland (former Galicia). Her recognition extended beyond the Jewish community – for one, she received the Order of Polonia Restituta, the Polish state award. This was the golden age of her career, which saw the creation of a network of vocational schools for Jewish youth, WUZET.

In April 1938, the United Galician Jews of America held a large congress in New York with more than 900 attendees – including Klaften. One of the main topics was the Nazi annexation of Austria and the difficult situation of the Galician Jews there. President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a telegram to the participants that mentioned Klaften by name, while the mayor and governor of New York attended in person and were both photographed with her. Klaften presented the work of the WUZET school network.

Upon her return, she was interviewed by the Galician Jewish writer Rachel Auerbach, and spoke with excitement about the scale of the event. She was especially moved by the way Jewish émigrés had asked about their hometowns in Galicia. She saw in this a deep attachment on the part of Jews to their land – and a yearning for their own homeland.

Cecilia Klaften’s success rested not only on her organizational skill and ability to secure funding – including from bodies such as the American Joint Distribution Committee and the Jewish Colonization Association in Paris – but also on her warmth and personal dedication. Interviews reveal a woman genuinely devoted to her students, many of whom stayed in touch with her for years.

One of her best-known pupils was Paula Staut from Stryi, who later emigrated to Paris and then to the United States. During a visit to America, Klaften brought samples of her students’ work to display at Staut’s atelier and even discussed possible collaborations with the Macy’s department store chain.

Yet, as with the vast majority of prominent Jews of interwar Lviv, the biography of Cecilia Klaften cannot be read without its tragic end. During the Nazi occupation, the elderly Cecilia Klaften continued organizing aid within the ghetto. She was murdered in the Holocaust in 1942.

Because she was known in the United States, the New York newspaper The Forverts published a feature about her death in 1946 with testimony from Cecilia’s friend Rysia Weisbach: Weisbach had tried to help the seventy-year-old Klaften escape to Warsaw, but she had refused, saying that her salvation would mean nothing if everyone else perished.

This story is especially poignant given the essence of her life’s work: creating opportunities for young people and helping to build a world where even the poorest and most marginalized could shape their lives.

Only a few survived from the Galician Jewish community. The building that once housed the vocational school still stands on Pekarska Street in Lviv. After World War II, during the Soviet era, it was converted into workshops for the Technical School of Light Industry. The school’s plaque is gone, but the faint outline where it once hung remains visible on the wall.

Translated from Ukrainian by re/visions.

Copy-edited by Katharine Quinn-Judge.