From Warsaw to Marseille and back: Julia Pirotte’s many journeys

How does one discover a major woman photographer of the 20th century? I came across Julia Pirotte’s work at an exhibition in Marseille, a city where she had lived and taken part in the anti-Nazi resistance. I followed her trail until I met her years later, in her city, Warsaw.

Marseille, autumn 1989.

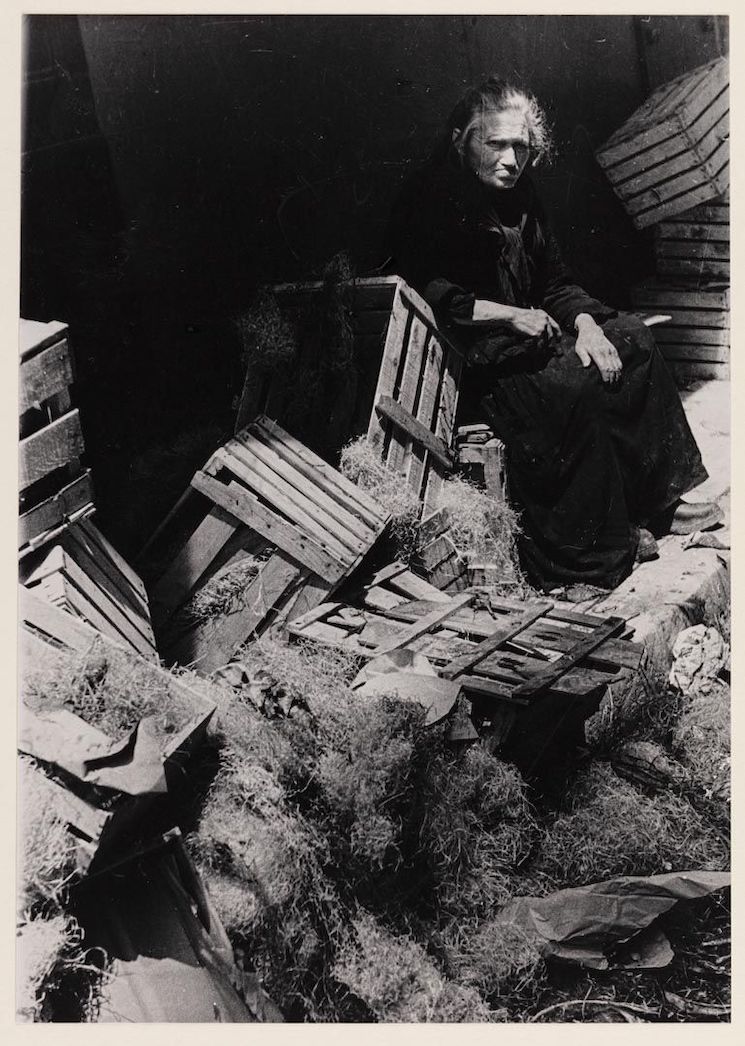

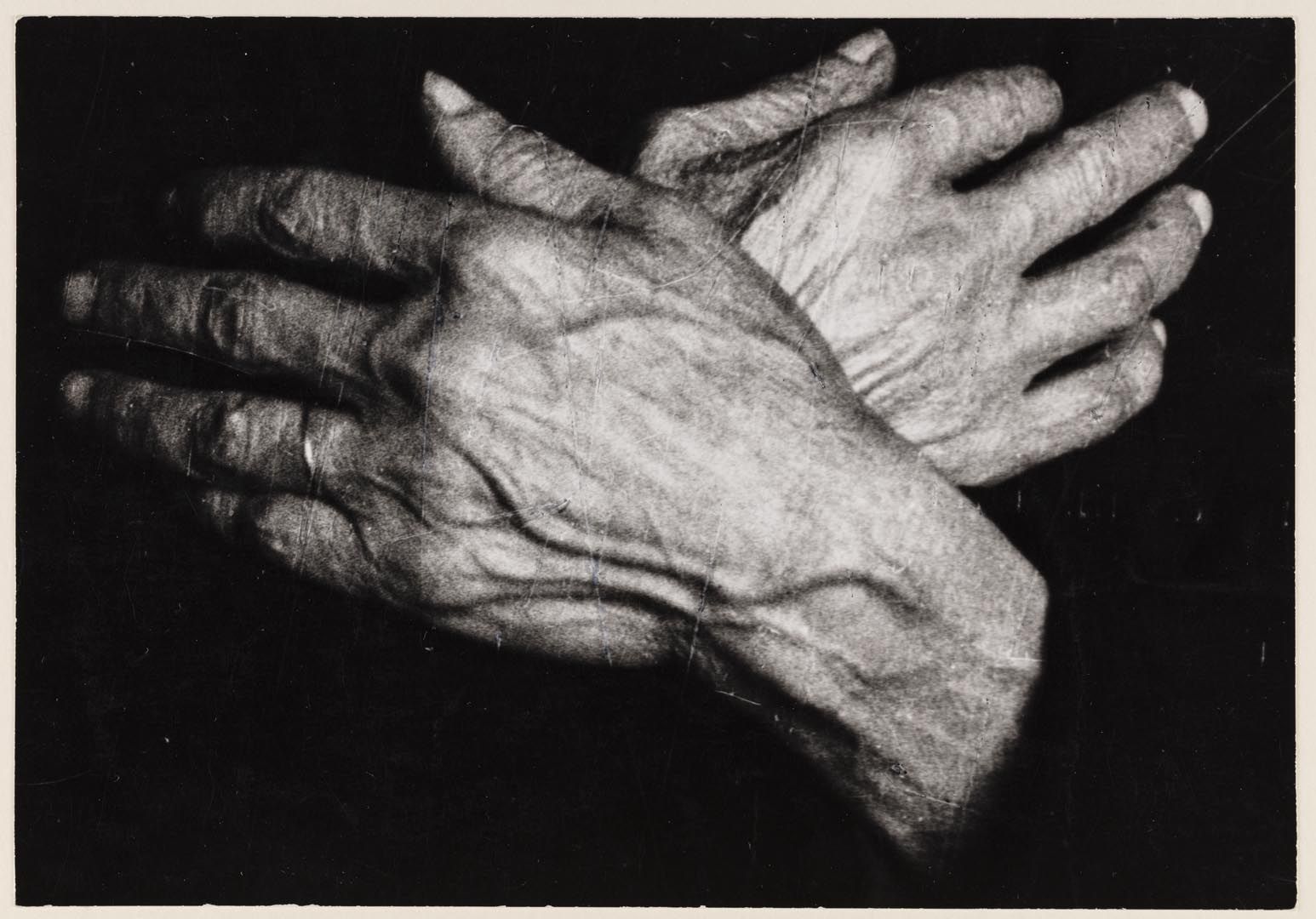

In the municipal hall of Marseille’s Belle de Mai district, I’m visiting an exhibition dedicated to the French Resistance in this city during World War II. It's been put together by a veterans' association with makeshift resources, but the photographs presented on wooden panels are eye-catching. They were taken during the Marseille uprising against the Nazis, in August 1944.

There's nothing heroic or sensational about the pictures; on the contrary, they show ordinary situations and gestures. I note the name of the photographer: Julia Pirotte. She seems so close to the insurgents when she trains her camera on them, she must surely be one of them. Is she still alive? — I wonder. The exhibition’s organizers hand me the telephone number of a woman called Hélène, who had herself been in the Resistance alongside Pirotte. I call her. She tells me Julia returned to Poland as soon as the war ended. Before she left Marseille, Julia had given her Resistance comrades these photos describing their struggle. Hélène tells me she hasn't heard from Julia since.

Warsaw, February 1991.

Through a series of contacts, I’ve ended up with a telephone number in Warsaw. I had called Julia Pirotte. I told her I was a historian carrying out some research about foreigners who took part in the French Resistance, and that I wanted to meet with her, to hear her story. “If you want to see me,” she replied, ”please ask Hélène to write me a recommendation letter for you”.

43 Pułaska Street, in Warsaw’s Mokotow district, is the address of a modest four-storey building dating from the 1960s. Julia Pirotte lives in a small two-room apartment. When I reach the 2nd floor, I ring her doorbell. A frail elderly lady opens the door. The first contact is disconcerting: she stands there very upright, with a determined look, and asks me for Hélène's letter. She gestures for me to stay on the landing while she reads it. After which, she finally smiles and welcomes me in.

Later, she would tell me the rest of the story: Hélène had signed her letter “Bella” which was her real first name known only to a small number of comrades in the Resistance. It was a sign Julia could trust me. Such a conspiratorial manner made me smile. I'd come to discuss her years in France: were the reflexes of her clandestine life all those years ago in Marseille coming back unconsciously?

For Julia Pirotte, the French Resistance had been just one of many chapters in a life full of commitments and struggles that began during her teenage years. She was born Golda Djament. She was no longer a child when the October Revolution broke out in Russia. Communist hope made her a revolutionary. She was just 17 when a court sentenced her to four years' imprisonment. She came out of it seasoned. The underground struggle continued onwards in Poland, then Belgium and France. She experienced twelve years of exile before being able to return home. In Poland, by then under Communist rule, Julia soon found that her long absence could arouse mistrust.

I immediately felt admiration for Julia. Admiration is an understatement. I was fascinated by her life of courage. Our first meeting was followed by visits to Warsaw each year or so until her death, in July 2000. I invited her twice to Marseille, where she met up with friends from her Resistance days. Admiration and fascination gradually gave way to affection.

Charleroi, May 1993.

I’m here to meet Julia at the Charleroi Museum of Photography, where Georges Vercheval and Jeanne Vervoort, the museum's founders, are helping her prepare a book about her work. They had discovered Julia at the annual Arles photography festival in 1980, where she had been invited to her very first exhibition. Recognition in Poland would come later. Jeanne and Julia had become friends, sharing a feminist consciousness and a commitment to activism.

Belgium, Charleroi. Could this be a mere coincidence? It was in Belgium that Golda Djament had become Julia Pirotte; it was in and around Charleroi that she had shot one of her very first photo stories on Polish miners.

In 1934, Golda was 26 years old. Four years in prison had not dampened her determination. Once again threatened with arrest, she had been sent to Belgium: the Communist International needed activists of her caliber to “organize” Polish immigrants. There were many of them in the mines, and Golda was a miner's daughter. The following year, perhaps due to her trade union activities, she received an expulsion order. She escaped by marrying Jean Pirotte, a Communist worker. It was a marriage of convenience — with, in the bargain, Belgian citizenship for her, a precious sesame.

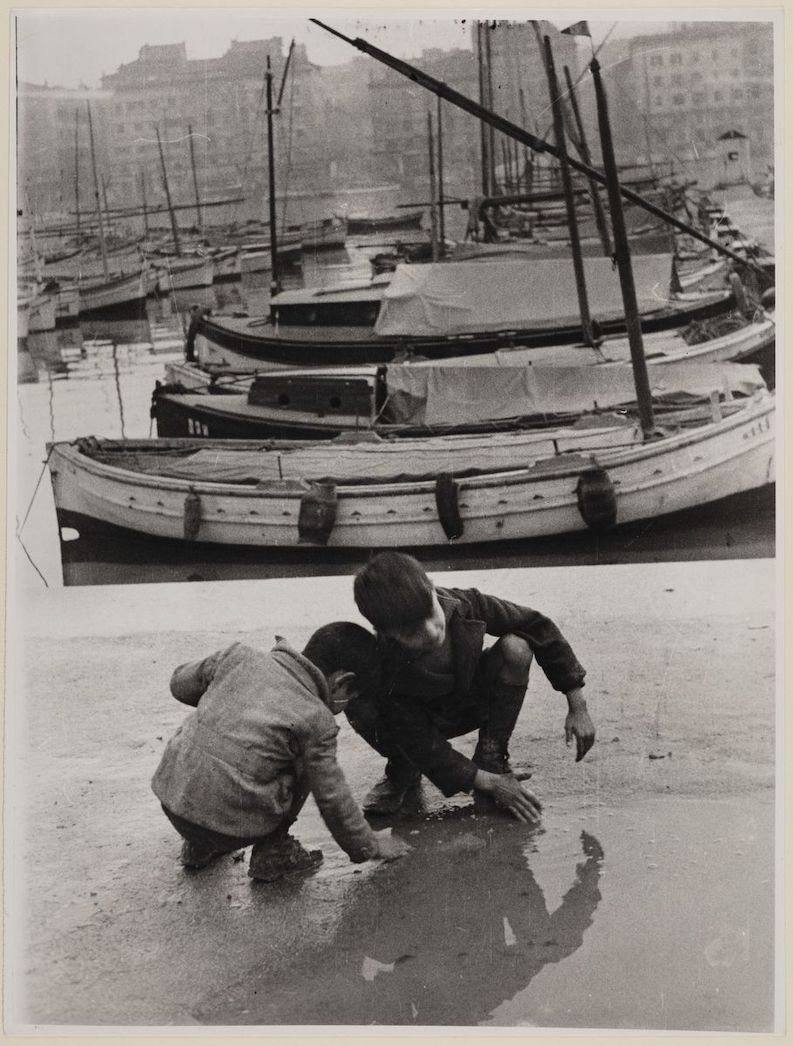

Following the strikes of June 1936, Julia was laid off from the factory that had employed her. She wrote articles for Party newspapers and took photography classes. But her real school, she would later tell me, would be the beach of the Catalans in Marseille, a location where she earned her living as an itinerant photographer during the war years.

Warsaw, April 1994.

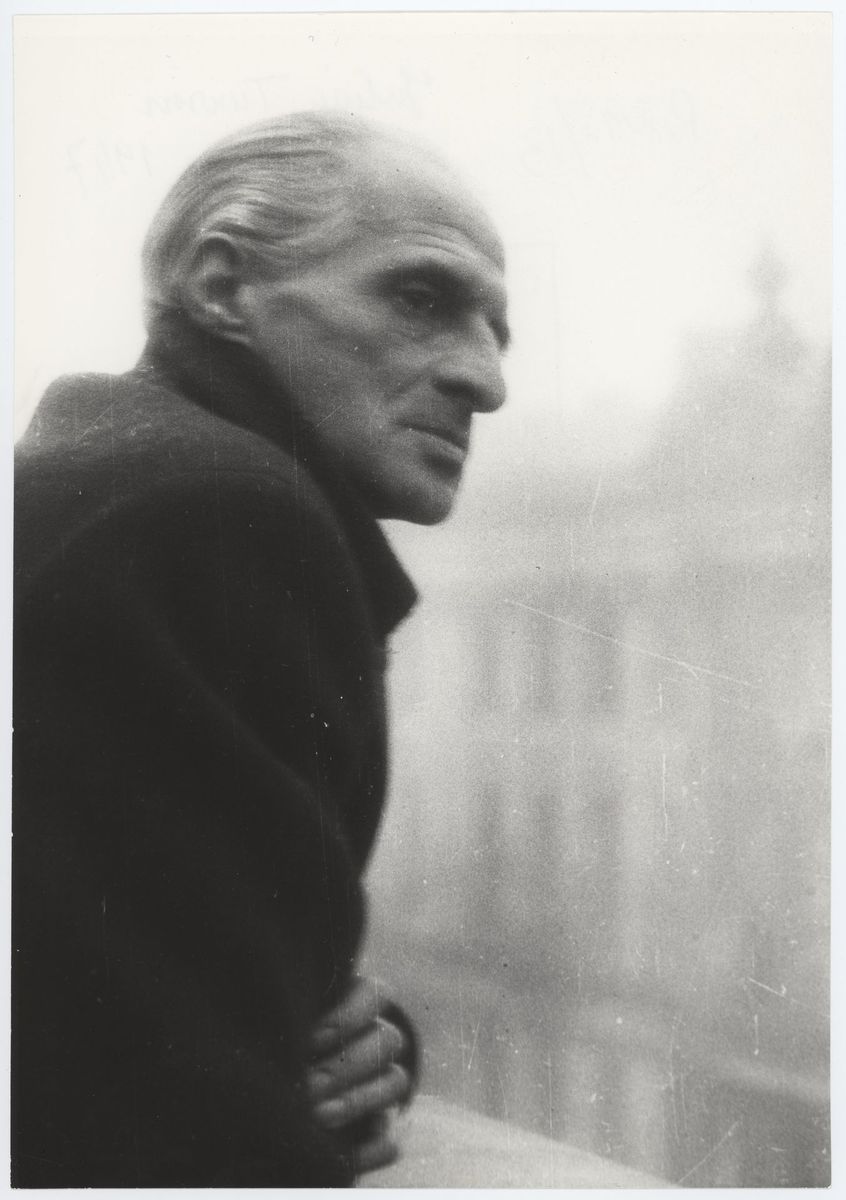

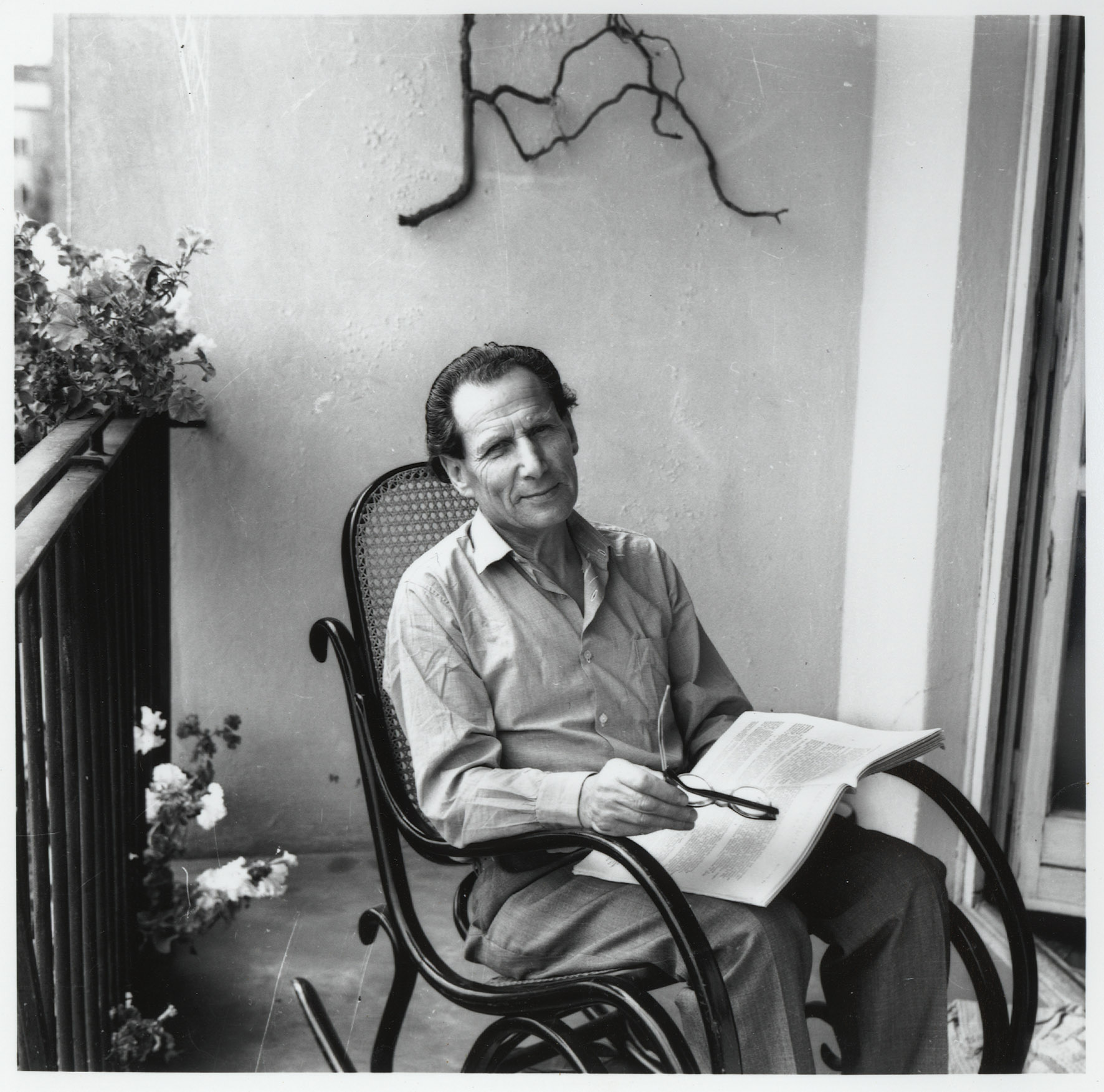

From the very first time we met, I'd noticed in her living room a portrait of a man sitting in a rocking chair, head bowed, a gentle smile on his lips. I end up asking Julia who this man was. Jefim Sokolski had been her husband. It was a long story.

Golda and Jefim were in their twenties when they met. Both were Communists. The repression that hit the Party at the time in Poland tore them apart: she left for Belgium, he sought refuge in the Soviet Union. They would not meet again until a quarter of a century later. Jefim was arrested in 1937 during the great purge of the Polish Communist Party ordered by Stalin. Sent to the Gulag, he spent 21 years there before being released and allowed to return to Poland.

Julia had no words to describe the moment they were reunited. I imagine their astonishment when they came face to face, and their love after so many years, after such a long silence. Julia and Jefim immediately got married, and lived together for 16 years until Jefim's death.

Julia never said so, but Jefim's tragedy must surely have shaken her political beliefs. I thought she had been “protected” under the Communist regime by the fact she belonged to the military - Julia had after all founded the Polish Army's photographic agency. One morning, I shared that thought with her. “You're wrong,” she replied. She said nothing else.

In 1951, a Polish defense minister had declared the following, in the middle of a Central Committee plenum: ”The time is now over when all the Jews were considered loyal”. And so it turned out that, in the army, in that place of power, Julia had not been protected. On the contrary, she was at risk.

And yet, she never wanted Poland to be criticized. In Marseille, a fellow former Resistance member had tried that. I watched a scathing Julia lash out at the woman. Many years later, I came across a text that shed light on this paradox: “Communists are people that harbor two souls, one for themselves and one for the outside world”. Bernard Mark, who headed Warsaw's Jewish Historical Institute, had written that in his diary.

Did Julia ever regret her Communist attachments? I once asked her. “Isn't it worth fighting for a fairer world?” she had answered.

Warsaw, September 1995.

On her living room table, Julia spreads out the contact sheets of her collection of photos as well as small cards on which she’s written dates, places and the names of people photographed. For months, Julia has been sorting her pictures. She’s decided to entrust all her negatives to the Charleroi Museum of Photography. Before she parts with them, there are pictures she wants to look at again, and others she wants to keep hold of.

Julia had set up her photo lab in the bathroom. The enlarger sits on a shelf among the linen; in the bathtub, she can line up the basins containing the developer, stop and fixer liquids. Above, hangs a string with clothespins. And there's Julia developing her photos. She's just turned 87.

Shortly before her death, Julia Pirotte donated these prints, hundreds of them, to Warsaw's Institute of Jewish History. They can now be viewed on the Wirtualne Muzeum Fotografii.

Marseille, December 1999.

At Hélène's funeral, a friend of hers, a rabbi, speaks. “She was an atheist,” he recalls, before invoking a tradition of Jewish mysticism according to which we have three names. “The one we are given at our birth, the one we build over the course of our lives, and finally the one leave in the memory of future generations”.

Golda Djament, Julia Sokolska, Julia Pirotte, three names for one same person.