Hannah Arendt and the meaning of friendship: an interview with Roger Berkowitz

One of the most delicate and profound threads in Hannah Arendt’s thought concerns friendship. Arendt regarded friendship as the foundation of both ethical and political life: a relationship that allows individuals to appear before one another as free and distinct beings. In contrast to love, which fuses two people into one, friendship preserves independence while cultivating respect and trust over time. We asked Roger Berkowitz, an American scholar fascinated by Hannah Arendt, to shed light on her understanding of friendship.

Why did you choose to dedicate your intellectual life to Hannah Arendt’s works?

Many people might think that founding the Arendt Center is something you sit down and rationally choose to do. That wasn't the case with me. I went to grad school in Berkeley to study pluralism and law. And because I spoke Russian at the time, I got a fellowship and was supposed to spend a year studying the Russian federalist structure and legal pluralism. But when I got to Moscow to start my fellowship at the Institute for State and Law, it had become a private law firm and ceased to exist.

When I got back to Berkeley, I realized I wasn't going to continue with that topic, and I started reading Martin Heidegger, the German existentialist philosopher. That resulted in my writing a very Heideggerian book about legal history and how science and technology change the nature of law and justice, called The Gift of Science.

Then I was offered a job at Bard College, which houses Hannah Arendt’s personal library and where Hannah Arendt is buried. I had always liked her work, and since it was 2006, the 100th anniversary of her birth, I organized a conference called Thinking in Dark Times: Hannah Arendt on Ethical and Political Thinking. The conference was unique – not too academic – because we asked people to come and speak freely, without papers, about why Arendt matters in the world.

Afterwards, the executor of her literary estate, Jerome Kohn, said that he’d been to a hundred conferences on Hannah Arendt, and this was the one she would have loved. He suggested I take over the Hannah Arendt Center, despite the fact that I wasn’t a Hannah Arendt scholar. That was nineteen years ago, and that began my journey into Hannah Arendt’s work.

Obviously, if there weren’t many things in Hannah Arendt's work and life that resonated with me, it would not have worked. That year, in 2006, I did a seminar on The Origins of Totalitarianism, a book that I think many people own but very few people read entirely. It's a long and difficult book. I read it with thirteen students, chapter by chapter over four months, and it changed my life.

First, I realized that all of Arendt’s work written over the next twenty years was already prefigured in this book. And second, I understood how profoundly meaningful her thinking was, not only about totalitarianism, but also about politics and human life.

That’s how I started teaching Hannah Arendt and writing a little bit about her. For about ten years, when people would ask me, “Why Hannah Arendt?” I would say, “It's because she's the greatest thinker of freedom that we’ve ever had.” For her, to be human is to be free. And to be free doesn't mean having free will; it means to act in the world with other people, to act in concert, as she says, and thus to have the courage to leave the security of your private life, venture into the world, and take risks, building something new and together.

Now, I don't think that's the wrong answer, but I've changed how I answer that question. Now I say that she's the great thinker of human meaningfulness. Freedom is not the end for her; to live a meaningful life is.

For Hannah Arendt, what makes us human is to be able to speak and act in public in ways that matter; to be able to speak and act and be heard by others, seen by others, with our speaking and acting taken seriously.

Speaking and acting means being free. But in the end, the truly human right, I think, for her, is the right to be remembered, the right to matter, the right to make an impact on the world. That's what humans want: to be meaningful. They want their actions to be seen, responded to, heard, and listened to.

One important way in which we matter and are seen and heard is through friendship. Both personal friendship and also political friendship, which for her means to be respected by your fellow citizens when you're given the right to have your opinions, even when they differ from others’, and still remain a citizen. That's the core idea of political friendship, as she understands it: that there's a bond that holds us together, which is not that we agree, but that we respect each other.

This kind of bond does not appear by itself. It requires work and a very particular kind of thinking and openness towards people. How do you distinguish personal friendship from the political kind?

Arendt’s friend, Hans Jonas, said that she had a genius for friendship. As an exile, as someone who was arrested and then stateless for eighteen years, she held on to her friendships with ferocity and fought for them, even when some of her friends tried to abandon her because they disagreed with her about certain issues. So how do you form that bond?

What makes two people decide to become friends is a difficult question. The French nobleman and essayist Michel de Montaigne explored this and eventually said, “If you ask me why I was friends with Étienne de La Boétie, it’s because I am me, and he is him. There's no explanation for how we became friends.”

Arendt has a little bit more to say about that than Montaigne. On one level, she says that you form a little homeland, a micro-world, with a friend. And that, I think, is similar to Montaigne: why do you form a micro-world with one person and not another? It's a je ne sais quoi. It’s hard to say.

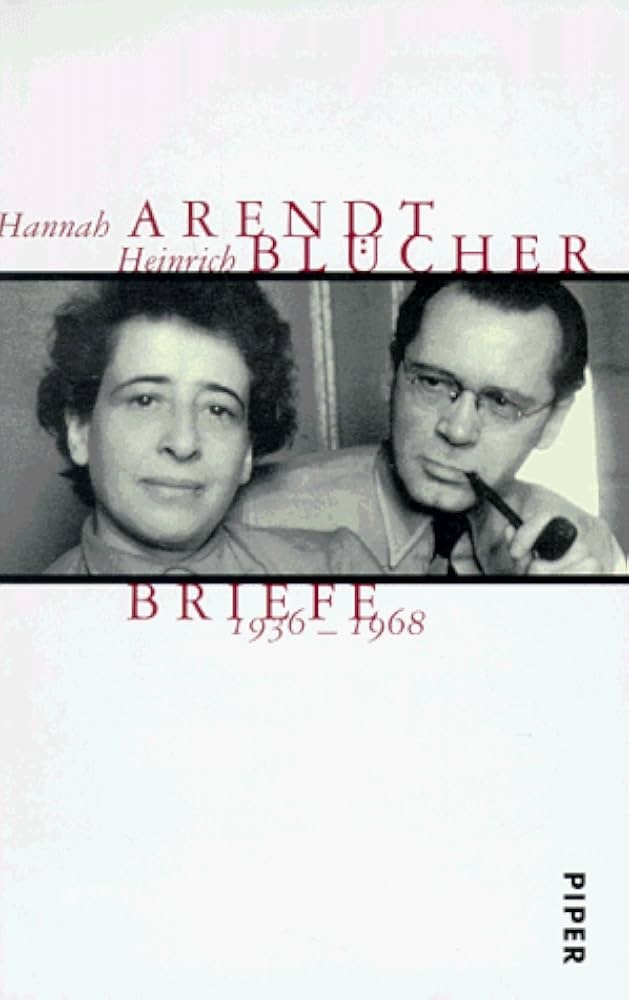

Her husband, Heinrich Blücher, was one of the two or three people that she was closest to. He says that there's an eros to friendship, which is then overcome. There has to be some sort of erotic bond that doesn’t go away but is turned into friendship.

Duration and trust are also essential for her understanding of friendship. For her, you can't become friends with someone quickly. It takes time; sometimes it takes years. In one letter to Kurt Blumenfeld, she claims it takes ten years to form a friendship. In another piece she wrote on the poet, W. H. Auden, she said it takes at least fourteen years. I don't think the actual number of years matters: the point is that friendship grows over time and can't be made quickly.

But the most important part of friendship for her is that, unlike love, which strikes you like a lightning bolt and forges two people into one, friendship is about respecting and recognizing your friend as fully independent, different, and unique. And you still respect and love them as a friend even though, at times, you fundamentally disagree with their opinions or the way they live. You don't have to really like everything about them, but you have to respect them enough and give them the freedom to be themselves to still be friends with them.

How does that happen? Well, as I said: trust, time, and a kind of secret ingredient. Arendt talks a lot about this in her letters and in some of her writing. In her more political writing, she talks about it more in a political sense. What does it mean for Ukrainians to be Ukrainian? Or for Americans to be American? Where does that bond come from? Who knows where it comes from originally, but at some point the bond becomes meaningful. And if we're going to have a meaningful pluralistic world, we have to learn to respect and value our fellow citizens and see them as our friends, as our co-nationals. Even when we don't like them. Even when we find them offensive. Even when we find them disagreeable.

There were many people after World War II who argued that we should get rid of nations, we should get rid of countries, and we should have a world government. She completely disagreed with that. She believed that humans need local, tribal bonds, as we can't live meaningful lives without a group of people who you can speak and act in front of, and they will hear and listen and respond. And she also thought that the world is too big, so you need distinctions and smaller entities. She worried that if we had a world government – and all governments are prone to tyranny and totalitarianism – and it became totalitarian, there'd be no escape.

How do we maintain our personalities and not dissolve into those “local bonds”? How to avoid a tribal, conservative, closed perspective on the world around you?

Friendship means giving people the space and the right to be individuals and to have their own opinions, right? What Arendt loved about Heinrich Blücher, her second husband, was that she had always thought that to be in love would require sacrificing her independence. Her relationship with Blücher was the first relationship with a man where he treasured her independence rather than trying to make her agree with him.

The very essence of friendship is to allow you to be independent. That independence also carries a bond. She had friends that she loved even when she didn't like what they did. The same with being an American or being a German, right? Somehow you find this bond that you hold onto, and you recognize other people as your co-nationals or co-citizens. That's plurality.

There were limits to what friends can do, though. For example, Arendt had friends in Germany, many of whom not only joined the Nazis, but worked with them throughout the war. After the war, some of them tried to reconnect with her. She refused, as there were limits to what she could recognize and accept. But there were others who joined the Nazis in 1932 or 1933 and stopped working with them by 1933 or 1934. She said, look, people are different, some people make mistakes, and I have to talk to them on an individual basis and try to understand them. For her, they hadn’t crossed the line; they did not participate in killing Jews, which started later than 1933.

What about her friendship with Heidegger? He was involved with the Nazis, but Arendt continued to exchange letters with him after the war.

Arendt met Heidegger in 1926 or 1927, when she was a student, a brilliant one. They became lovers for a period of time, and he sent her to work with Karl Jaspers in Heidelberg.

With the rise of the Nazis, Heidegger in May 1933 became rector of University of Freiburg, and even gave his famous rector's address, The Self-Assertion of the German University. Arendt heard a lot of rumors about him, including that he had, in a sense, fired Edmund Husserl, which is not entirely true. She came to believe that it was. Heidegger had taken away some of Husserl’s privileges that he was supposed to have retained. So Arendt cut off her connection with Heidegger during the war and didn't talk to him for many years.

In 1950 she was in Europe doing work for the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction Commission. She didn't know whether she would see Heidegger or not but decided to do so. They ended up walking in the woods and having a long talk. She said that Heidegger was honest with her and treated her as a human being, as a full person, for the first time in their lives. So she made the decision to continue a friendship with him.

We don't really know what they talked about. There are some hints, some letters. We know they talked about reconciliation, a theme that becomes profound in her work, from that point on.

Arendt distinguishes reconciliation from forgiveness. She doesn't forgive Heidegger, but she reconciles with him. And the idea here is that to reconcile with someone, there has to be a mutual release. They have to ask for it; they have to admit that they were wrong and that they had done something for you to release them from that guilt.

It's not a forgiveness. It's not saying, “I would have done it too,” or “We're all equally capable of doing it,” or anything like that, but rather an assertion of solidarity, that even though this person did it wrong, she still believes she can build a common world, a homeland, with this person, a new life together.

Heidegger had joined the Nazi party; he never withdrew from it. By 1934, he had served as rector for about a year before resigning or being removed. He withdrew from public life and was put under house arrest by the Nazis. He went into internal exile during the war, teaching private courses in his home, which, if you read those courses, are clearly anti-Nazi courses. He certainly held anti-Semitic opinions, though.

In her book The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt distinguishes race thinking from racism. There's an abyss, she says, between men who have bad ideas and men who are bestial – who go and kill people. Heidegger never went and killed people. This is not an attempt to forgive or whitewash what Heidegger did – what he did was wrong – but she didn't think it was something that disqualified their friendship.

Not everyone agreed with her. For example, one of her other best friends, Karl Jaspers, who had been very close friends with Heidegger before the war, never reconciled with him. There were differences: Jaspers had also stayed in Germany throughout the war, and his wife, Gertrude, was Jewish. Heidegger cut off relations with him. Jaspers could never forgive that and never reconciled with him afterward.

Arendt understood that. She said to Jaspers, “You have your relationship with Heidegger; I have mine. I can reconcile with him, and you have to let me do that.” And when Jaspers tried to push her into cutting her ties with Heidegger completely, she refused, saying, “No man is going to tell me what to do. If you want to try and tell me who I can be friends with, we’re done.” He relented, and they maintained their friendship.

In the end, I think her judgment about Heidegger was very principled and quite meaningful, and it led to many reflections of her about reconciliation, solidarity, and politics that I find incredibly profound and meaningful today.

In one of your public speeches, you mentioned that Arendt preferred friendship over truth. Now we are witnessing something happening with the notion of truth, which is being manipulated in probably unprecedented ways. How do you address this connection between friendship and truth in your upcoming book?

That is the core of the book. Arendt makes it very clear in a number of her published essays: friendship is more important than truth. At the end of her essay The Crisis in Culture, she says it's better to go wrong with your friends than to be right with your enemies, which is a challenge to many people today who believe that truth is so important.

In another essay, Truth in Politics, she claims that it would be crazy to say, “Let justice be done, even if the world perishes.” She says that justice is a good thing, but it's better to have the world continue than to have justice and all die. But, for her, you can't say that about truth, because you can't have a world without it.

For her, the truth that we need to fight for is not certainty, but the lowest common denominator we share – a common world. The idea of respect as a fundamental friendship is politically more important than agreement on fundamental issues.

That's how she came to understand politics, in a very Aristotelian way. Aristotle had said that friendship is the bond of the polis.

How do you think friendship has changed since social media was introduced? It appeared to be the ultimate way to bond, but in fact, we see it adds to polarization and loneliness. What do you think happened?

We all talk about a crisis of truth and a crisis of politics. But it may be that the crisis of politics is not based on the crisis of truth; it's based on the crisis of friendship.

I think it started long before Facebook. Hannah Arendt already wrote that the rise of modern loneliness can be traced to the early 20th century, and the reason for that is what she called the shattering of the pillars of tradition. She says that tradition, carried over from the past, gives our lives a kind of banister, things that we live according to, structures. One was supposed to live a certain way, to be a farmer, for instance, or to live in a city and have customs. Things changed slowly. As a result, one knew who one was, and a life had meaning and purpose because of this knowledge.

But with the rise of individualism, the rise of democracy, and the throwing off of religion, family, and tradition, suddenly you could be anything you wanted. You could be free. You could define yourself any way you wanted. And that's obviously an enormous power. But with it comes what Arendt calls metaphysical loneliness – a sense that you don't really know why your life matters. Your life could be about being a journalist today, but tomorrow it could be about being a soldier, and the next day it could be about being a parent, and it's all free choice. Every single one of them can seem meaningless, like an accident. If you're going to suffer, you want to know that it's for more than an accident. That's the kind of meaninglessness and loneliness that Arendt saw as endemic to the modern age.

Facebook and social media are more of a symptom of this almost 150-year problem of the rise of mass loneliness that Arendt understood and tried to write about in her work. Social media is simply a way for lonely people to try and find connection – a way that doesn't really work, doesn't make them less lonely. It's supposed to, but it doesn't.

I sometimes learn that someone got married or someone’s mother died because I see a Facebook post about it. If I'm a friend, we should talk about these things in real life. “Like”? Or “hugs”? That's not friendship.

The result is that we have this simulacra – a belief in friendship, but not real friendship.

My friend Niobe Way has written a number of great books on the problem of male friendship. Men, especially young adolescent men, are taught to not get too close or show intimacy, to be independent, cold, rational men. And the result is that men are suffering from loneliness today in a way that is quite dangerous, leading them to seek meaning in political movements, totalitarianism, et cetera.

No one can have a hundred friends. You can't talk to a hundred people every week about your life. But there should be two to four or five people you do talk to weekly.

Can friendship, and being able to sustain a friendship, be an antidote to the rise of totalitarianism?

Arendt never put it that way, that I know of. The only time she ever talks about an antidote to totalitarianism is in the introduction to The Life of the Mind, in the section on thinking, where she raises the question of whether thinking is a prophylactic against potential totalitarianism.

Thinking for her means to think from the perspective of another, and thus to be friends with someone. So I think there's a connection: if you have friends, not only do you find someone you share a homeland with that gives you a sense of purpose and meaning, so you don't need to seek it elsewhere, but also you have someone who disagrees with you, who sees the world differently, and you learn to value and listen to and trust different opinions.

In that sense friendship and thinking are both anti-totalitarian. They are designed to teach you to think from the perspective of others, which is precisely what totalitarianism doesn't want you to do.