Nina Henke (1893-1954), a trailblazing artist

Nina Henke played a formative role in the early 20th-century revival of Ukrainian folk art and its transformation through modernist aesthetics – yet she is often overlooked today. Her embroidery designs for pioneering workshops brought a bold visual language of geometry, color and rhythm, inspired by traditional peasant craft. She was a key mediator and innovator within a network of women artists and patrons. Her career unfolded against a backdrop of war, revolution, and loss, which obscured some of her work. We want to bring her legacy to the fore.

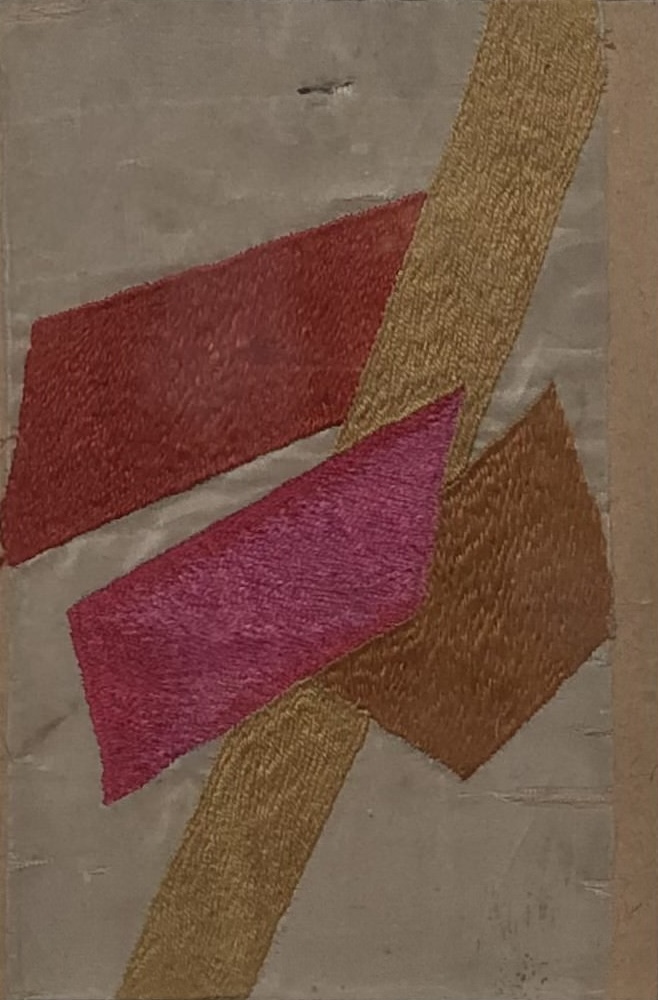

In November 2021, I visited a recently opened Futuromarennia exhibition at the Mystetskyi Arsenal art center in Kyiv. Among the myriad showcased arts, I was particularly drawn to a small section featuring the work of embroidery workshops in the Ukrainian villages of Verbivka and Skoptsi. Two of the displayed embroideries had been created in 1916 in Verbivka, based on designs by the modernist artist Nina Henke.

While we tend to think of embroidery as a traditional craft, passed down through generations, Henke’s designs stand out as uniquely modern. Rather small, they emanate remarkable vibrancy and dynamism through interlinked geometric forms – fiery oranges, bright pinks, radiant whites, and sun-infused yellows floating on a beige moire background. These embroideries survive as rare witnesses from their era and reveal the talent of an artist whose art and life remain largely obscure. Importantly, they also mark a pivotal moment in Ukraine’s art that intersected modernist aesthetics with established decorative traditions.

As an art historian working on early 20th century Ukraine, I am used to encountering absences – artist names in catalogs without preserved artworks, documents lost or destroyed, and fleeting glimpses of those who vanished through war, dislocation, or repression, with few records remaining. Facts have often been erased, manipulated, or misconstrued in our country’s turbulent history.

The story of Nina Henke, an artist, theater designer, and educator, stands as a striking example of having more absences than facts. Though almost unknown today, Henke was instrumental in developing Ukraine’s modernist art and decorative practices. She also became central to a close-knit group of entrepreneurial and creative women who, in the early 20th century, cultivated an enduring engagement with Ukrainian folk art.

Nina Henke was born in Moscow in 1893 to Henrich Henke, who was of Dutch Lutheran descent, and his Russian wife, Nadezhda Tikhanova. At some point, the family moved to Kyiv, where Nina attended a private girls’ gymnasium run by Mariia Levandovskaia. Opened in 1904, it provided a seven-year instruction in languages (Russian, Ukrainian, German, and French), history, geography, mathematics, and physics. The girls were also taught the tenets of hygiene, drawing, and handicrafts. Upon graduating, Henke took exams that allowed her to teach history and the Russian language privately and in schools. Aged 19 or 20, she was assigned as a tutor of history and geography to a women’s college in Skoptsi. This appointment proved a turning point in young Nina’s life.

Skoptsi was home to the country estate of a liberal noblewoman, Anastasia Semyhradova, where she ran a textiles workshop. It was part of the handicrafts revival undertakings, popular in the Russian empire and across Europe at the time, as inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement in England. Seeking to alleviate the threat of modern life to the traditional ‘rural’ way of living by creating local employment for the peasantry, its proponents strove to preserve examples of traditional peasant production that were increasingly replaced by factory-manufactured items.

In 1910, Semyhradova invited the artist Yevheniia Prybylska to oversee the workshop’s running. Prybylska was a graduate of the Kyiv Art College and developed a keen interest in Ukrainian decorative practices while studying and copying examples of textiles from the vast collection of the Kyiv Museum of Industrial Arts and Science. In Skoptsi, she oversaw the workshop’s daily work, prepared designs for embroidery and carpets, and mentored several artisans, recognizing them as artists.

Prybylska seems to have played an equally pivotal role in Henke’s artistic development. The women's college, where Henke was teaching, shared premises with Semyhradova’s workshop. Henke must have been introduced to Ukrainian decorative arts there. A direct and unmediated exposure to Ukrainian patterns and techniques proved momentous: Henke subsequently abandoned her teaching career and fully embraced artistic pursuits. Under Prybylska’s tutelage, she started practicing embroidery and carpet weaving. Exhibiting a remarkable creative talent, within a couple of years, Henke swiftly progressed in her work and joined Prybylska in co-running the Skoptsi workshop in 1914.

One of the artisans whose talent Prybylska nurtured in Skoptsi was a young local girl, Hanna Sobachko. She first worked in the workshop as an embroiderer but was soon tasked with creating compositions on paper for transfer to needlework charts. As was typical for Ukrainian peasant women, the young artisan had learned how to embroider, sew, and weave from her mother. Less typically, at a young age, Sobachko began drawing rushnyky [runners] on paper for sale at a local market. At the turn of the 20th century, such paper decorations started widely replacing more customary wall paintings in peasant homes. It is likely that Henke and Sobachko worked together in Skoptsi. Their art, despite its many stylistic contrasts at first glance, displays a shared interest in chromatic brightness and complex compositions – traits inspired by Ukrainian folk traditions.

Henke and Prybylska belonged to Kyiv’s cosmopolitan society of Ukrainian, Russian, Jewish, and Polish upper-class strata. A prominent figure in this milieu was Natalia Davydova (née Hudym-Levkovych), a noblewoman, artist, collector, and patron of the arts, particularly peasant handicrafts. Like Semyhradova, Davydova was affiliated with a group of intelligentsia and gentry in Ukraine that sought to preserve local folk and decorative traditions. In the early 1900s, she set up her own textile workshop in the village of Verbivka on the Kamianka family estate of her husband Dmitrii Davydov.

Davydova was friends with an aspiring artist, Alexandra Exter (née Aleksandra Grigorovich). It is unclear whether Davydova met Exter, then still referred to by her maiden name, during their studies at the Kyiv Art College. An alternative theory suggests that the fateful introduction occurred via Natalia’s husband’s friendship with Alexandra’s fiancé, Nikolai Ekster. Regardless of its origin, this initial social encounter evolved into a decade-long personal and professional relationship that endured through revolutions, wars, and emigration. Exter and Davydova, who both practiced embroidery and exhibited decorative items alongside their paintings, played an active role in organizing the 1906 South-Russian Exhibition of Applied Arts and Handicrafts, at Kyiv’s Museum of Industrial Arts and Science. The same year, they became founding members of the Kyiv Handicrafts Society, with Davydova serving as its first chair.

Established to promote Ukrainian folk art across the Russian empire and beyond, the Society distributed the produce of several handicraft workshops, including from textile studios in Skoptsi and Verbivka. Prybylska was one of the artists the Society commissioned to create embroidery designs for these workshops, before she became formally affiliated with Semyhradova’s atelier. It is possible that Prybylska became acquainted with Davydova and Exter through her work for the Kyiv Handicrafts Society. A few years later, in 1914, the Society also employed Henke to supervise the activity of all its workshops in the Kyiv province.

In the summer of 1914, shortly before World War I severed all connections with the European art scene, Exter accepted Davydova’s invitation to oversee Verbivka’s artistic direction. In this role, Exter abandoned the established practice of creating designs that replicated 17th and 18th century embroideries, characterized by chromatic dullness acquired over time. Instead, Exter explored the vividness and dynamism of Ukrainian peasant drawings, embroidery, and Easter eggs.

Around the same time, Henke also joined the team in Verbivka. She eventually took over the studio’s artistic direction from Exter, who participated in multiple projects in Kyiv, Moscow, and Saint Petersburg. Henke was involved with at least one of these, assisting Exter in creating costume and stage designs for Aleksandr Tairov’s production of Thamira Khytharedes at his Moscow-based Chamber Theater in 1916-1917.

In late 1915, Henke, Davydova, Exter, and Prybylska staged an exhibition titled Contemporary Decorative Art: Embroideries and Carpets Based on Artists’ Sketches, at the Lemersie gallery in Moscow. Through Henke’s and Exter’s connection with Kazimir Malevich, the studio also commissioned a cohort of ‘leftist’ artists soon to be associated with his nascent Suprematism movement. In it, Malevich sought to abandon representation in favor of abstract geometric forms, with primary colors floating against a white background. Two embroideries designed in 1916 by Henke, which have been preserved, illustrate her link to this new artistic method. But their color scheme reflects a commitment to Ukrainian peasant drawings.

A lack of first-hand accounts and archival documents makes it difficult to describe how artists collaborated with artisans. Henke seems to have played a key role in this cooperation, translating artists’ sketches into needlework charts for artisans to reproduce in embroidery. At this point, both Verbivka and Skoptsi employed hundreds of embroiderers and weavers and had on-site fabric-dying facilities. In December 1917, Henke, Exter, and Davydova opened another exhibition in Moscow to showcase items from Verbivka. It presented 400 works designed by sixteen artists and embroidered by artisans in the studio.

This incessant activity would not last, however. Following the events of 1917, both the Verbivka and Skoptsi workshops ceased to function. The Bolsheviks destroyed Davydova’s estate in early 1919. The studio in Skoptsi closed after Semyhradova transferred all her lands to peasants and relocated to Moscow. The dispersal continued with Exter and Davydova eventually immigrating to Paris, and Prybylska and Sobachko moving to Moscow.

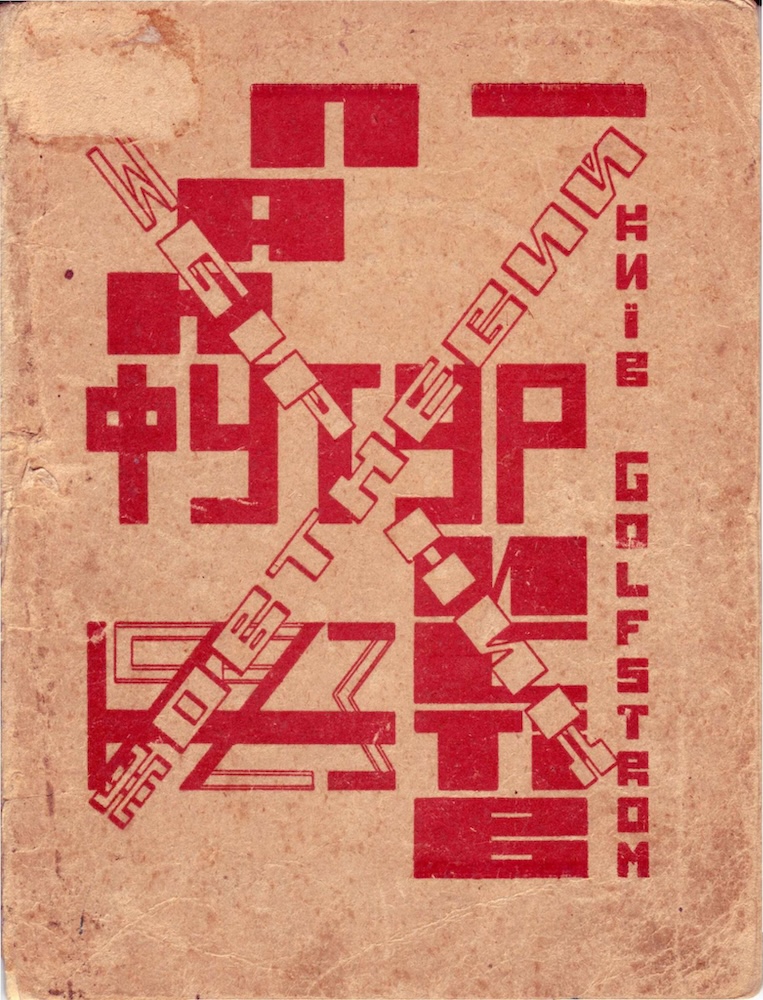

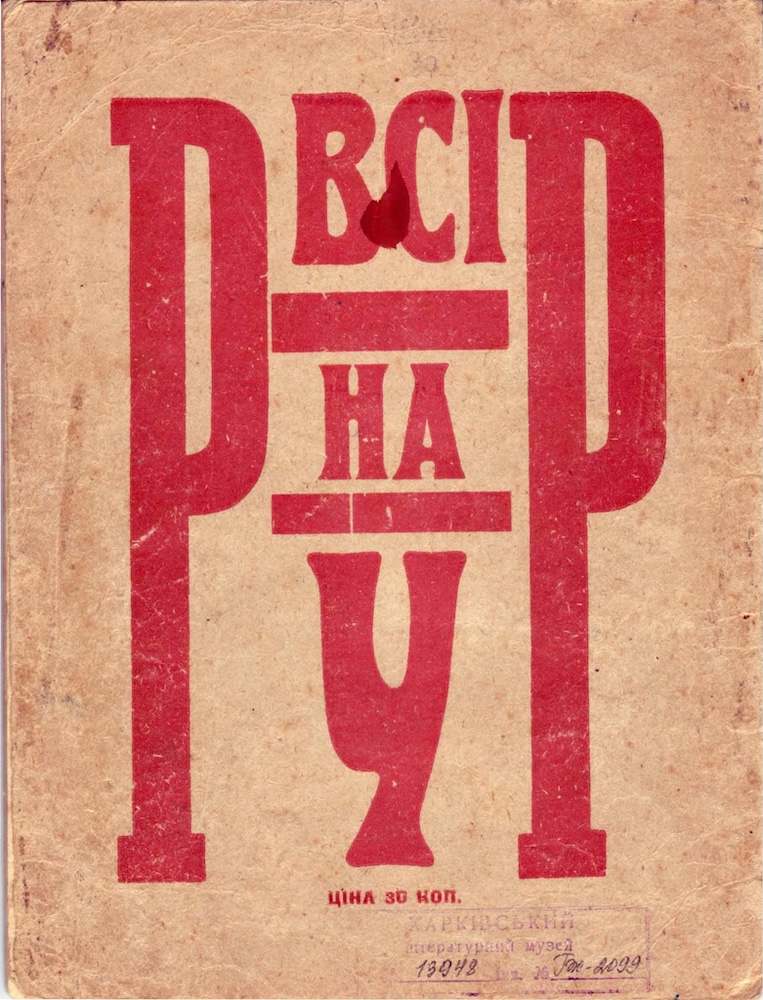

Henke, meanwhile, remained in Kyiv. In 1919, she married a fellow artist Vadym Meller. From that point onwards, she signed her works as Henke-Meller. Nina enjoyed a prolific artistic career in the 1920s, collaborating with such avant-garde practitioners as Les Kurbas for his Berezil theater and Mykhail Semenko during his tenure as the chief editor of the Gulfstream press. In 1923, she designed the cover for a volume of experimental poetry, October Collection of Panfuturists.

For some time, Nina and Vadym continued exchanging letters with Exter, who settled in Paris in 1924, recalling their years of common work in Ukraine and hoping for future projects. But those never materialized. Gradually, Henke switched to more administrative roles, prioritizing her family and her husband’s artistic career.

Most of Henke’s artwork was lost in World War II. During the Nazi occupation of Kharkiv, the Henke-Meller family apartment was looted. Paintings and decorative items created by both artists were seized by Nazi officers and possibly taken to Germany, but their fate remains unknown. In art historical accounts, Nina Henke’s name mainly appears as a footnote to the story of her better-known husband. Occasionally, it is mentioned in association with Verbivka, but always as an addendum to Exter and Malevich. Yet both her prominent role in running this workshop and the scope of her artistic career deserve to be remembered.