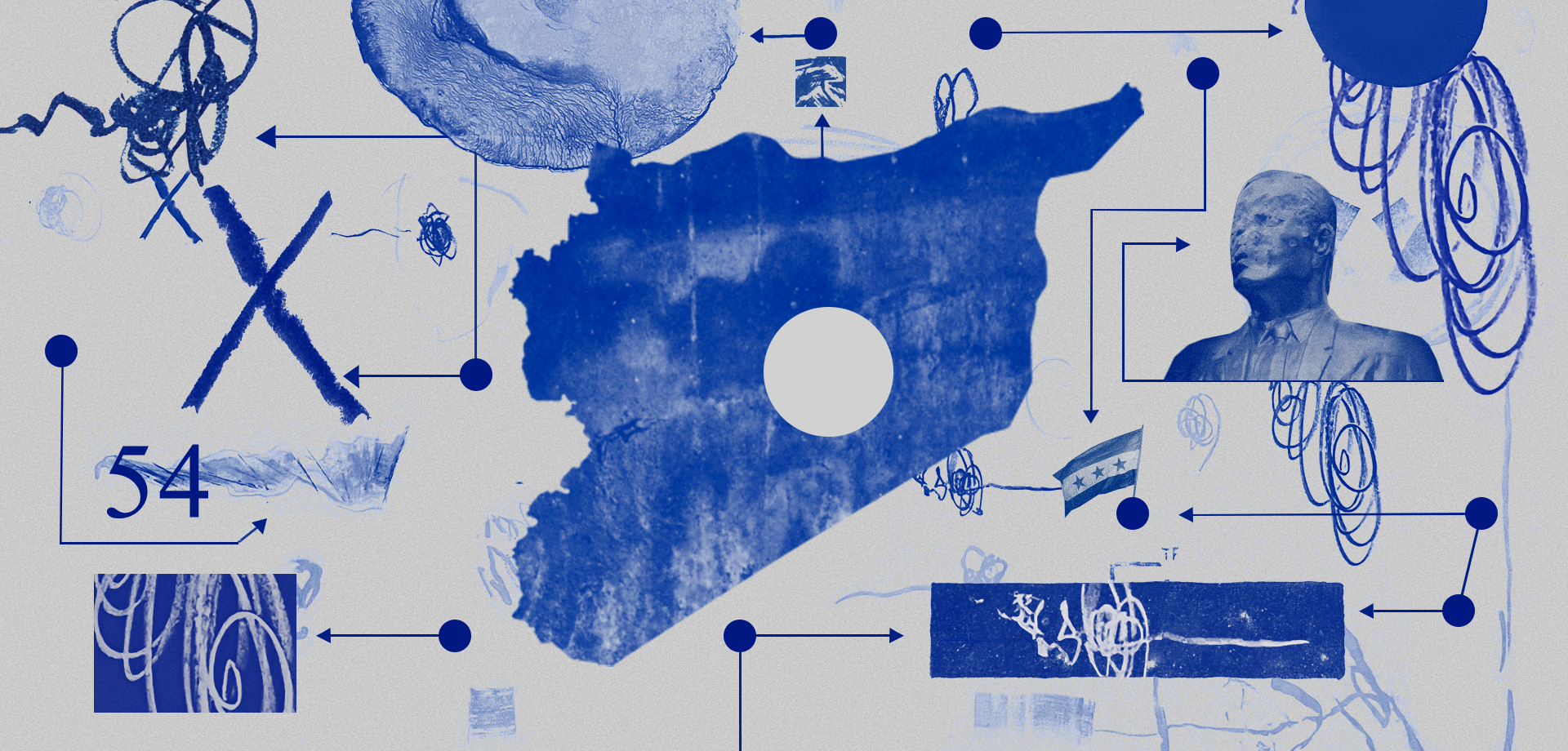

Not in a single voice: my generation’s task of writing Syria’s history

For 54 years, Syria’s history was written by the Assad regime through terror, lies and control. That ended on December 8, 2024, when Bashar Al-Assad was overthrown and fled to Russia. The fall of the dictatorship and the opening of archives mean that Syrians are now reclaiming their memory. But what truths will be preserved, and whose voices will be heard? In this essay, Syrian activist Jelnar Ahmad stresses the importance of building an inclusive and pluralistic historical narrative and resisting any version of history imposed from above.

“After all, some kind of history will be written, and after those who actually remember the war are dead, it will be universally accepted. So for all practical purposes the lie will have become truth.”

George Orwell. Looking back on the Spanish War (1943)

Last year, history changed in my country. On the early morning of December 8, 2024, Bashar Al-Assad, Syria’s dictator, fled on a plane to Russia, ousted after a ruthless rule of 24 long years. A dictatorship he inherited from his father, who suffocated and terrorized Syrian people for three decades. Yes, fifty-four years of father and son, fifty-four years of tyranny, oppression, and repression. After fifty-four years, Syria is not ruled by the Assads anymore. “Is this really happening?” was a question on the mind of many in the few days and nights leading to, and directly following, that morning. This was an event that every living Syrian will remember. It was the beginning of an era.

Several generations of Syrians don’t know or remember Syria without Assad’s rule. “Assad for eternity” was the de-facto slogan of the country, “Assad’s Syria” was its de-facto name. Those and similar phrases were sprayed onto walls, written on billboards, shouted in celebrations, and engrained into every brain. Streets, bridges, hospitals, schools and many other landmarks were named after Assad. Statues and portraits of the Assad family dominated squares and public spaces. Anyone who dared to dissent was brutally silenced. A state of oppression, a systematic killing machine, served the regime and its continuity.

When Syrians said “enough” and went to the streets demanding freedom and dignity, inspired and encouraged by the wave of uprisings known as the Arab Spring, the response was more cruelty, killing, forced disappearance, and a stronger hold to power. What started as a peaceful uprising turned into a civil war, a protracted armed conflict that played out as an arena of proxy wars for regional and international powers. The country was divided among powers, with de-facto authorities and warlords asserting their control supported by their financiers and political backers.

Fourteen years have passed since the beginning of the Syrian uprising of March 2011. During which hundreds of thousands have been killed, at least a hundred and fifty thousand missing, half the population displaced, internally or globally; and among those who remain, a vast majority live below the poverty lines. The Assad regime used every possible weapon and every possible means of oppression against its people. Bombing, shelling, siege, starvation, barrel bombs, torture, and chemical weapons. Cities and towns were destroyed, the economy and livelihoods obliterated, social ties torn apart, and facts and truth obscured and distorted. While the regime was responsible for around 90% of crimes and atrocities over the years of the conflict, it was not alone. Extremists’ groups, ISIS, Al-Qaeda affiliates, mercenaries and other militias have all played a role in the desecration of Syrians lives and dignities.

Throughout its long brutal reign, the Assad regime didn’t only use physical force to control Syria and its people, but followed various well-known strategies from the tyranny books. A policy of divide and conquer defined how Syria’s diversity was managed. Syria is home to eighteen different religions and sects, and about a dozen different ethnicities, numerous tribes and clans, rural and urban communities. The Assad regime exploited that by spreading fears, limiting connections, curtailing essential freedoms, and it exacerbated historical grievances in a region whose past is saturated with conflicts, wars and disputes. Syrian diversity turned into a tinderbox of social conflict and divides. The long years of brutal dictatorship followed by a bloody conflict have created overlapping grievances and victims-perpetrators groups, competing narratives and distorted histories.

Now that chapter has been closed. Today, history is being written, not as a tale of ancient past, but as a living, progressing present. So where do we start? How do we write it? What goes into it? Who gets to write it? What do we want to remember, and what to forget? What type of memories do we want to create?

Those questions cannot be separated from our struggle for justice. In the new era, the question of justice, and specifically transitional justice is on everyone’s mind. This new chapter of Syria’s history brings hope and great opportunities for a better future, but is also marred with hurdles of every scale. Syria faces the huge challenges of achieving justice for all victims and those affected by atrocities committed by the Assad regime and other actors; of healing and recovery from a collective trauma and rapture of national identity; and of building a peaceful rights-based nation for all its citizens. Seeking and establishing truth is without a doubt a linking thread of addressing all those challenges. Truth about what really happened during the last conflict and during the last five decades, truth as a basis for justice and peace.

In order to navigate through the strenuous path that lies ahead, we ought to establish this truth, preserve the memory and start building a new collective national identity, one that defines what it means to be Syrians beyond Assad; one that gives us our diversities and richness back; one that doesn’t blur the lines between a nation and a ruling class.

Many experts and activists argue for the need for a national archive, and for a collective unified memory that brings us together and bridges the divides. Many discussions in post-Assad Syria revolve around how to bring those bits and pieces together, how to coordinate and collaborate, and how to integrate the numerous civil society efforts into an official — potentially state-led — framework. This argument has a lot of merit, but at the same time, one can say, many pitfalls. On one hand, following years of fragmentation and divisions, it is of high importance to bring together the shreds, and find a unifying tone that helps us heal and move towards a better future. Syria is definitely in need of a national narrative and collective history that's accessible to all, and most importantly, equitable to all. However, those divisions are also not stories of bygone days. The trauma is still too recent, the transition remains unstable and ambiguous, attempts to obscure facts are notable, and the risk of another controlled narrative, dictated by the voice of power, is too big to ignore. In asking how we want to write our history, and in challenging the easy notions of top-down ready-made formats we may lead ourselves into finding that balance.

Fortunately, we are not starting from point zero. Over the past years Syrian activists and human rights defenders, media and civil society actors have been relentlessly documenting, investigating, archiving, fighting legal cases in international courts, theorizing and producing knowledge about our past, present and possible future. A wealth of knowledge and expertise has been accumulated, which can serve as building stones for a truthful collective narrative of the Syrian story. Various groups have set out to collect and organize evidence of human rights violations, the documenting of atrocities, oral history, creative arts, and historical records. Many of those are publically available, open to the world to reach out and see.

Syria’s liberation from the Assad regime has opened the door to access and obtain more information, to enhance and corroborate those efforts. Unfortunately, in the wake of the fall of the regime, massive amounts of documents, records and material evidence were destroyed. Some intentionally, others due to the negligence and chaos that supersede such a massive transformation. A huge network of prisons, detention centers and security forces branches served as the underlining structure of a police state based on systematic surveillance and torture, and all those locations were opened within a few hours. Detainees who were alive were freed, but thousands and thousands of families stormed those building looking for traces of loved ones who didn’t come out to the light, desperate for any clue, a piece of paper, a scribble on a cell wall, a photo, or the copy of an ID document, anything. For many there was nothing to find. Photos and videos from inside those locations started to spread like fire on the Internet, images of dark corridors and mouldy prison cells with mounds of paper laying on the grounds, torn to pieces, soaked with water, or burned to ashes.

More than a hundred thousand detainees are still not accounted for, and chunks of our history have been lost. Countless activists, human rights defenders and civil society actors, aware of the value of such evidence in pursuing justice and in preserving memory, raised the alarm, warning of the dangers of destroying evidence and calling for the need to preserve it. Several weeks passed after the liberation before the new authorities in Syria responded to these cries, and closed off all the sites of potential evidence. Meanwhile, many initiatives had started collecting and preserving what they could lay their hands on, adding to the mountains of evidence documented throughout the years. In certain cases, testimonies from witnesses and survivors of crimes can now be supported by official documents, and there is hope that the fate of the missing may be unveiled, perpetrators identified, and truth restored beyond doubt.

Syria’s new rulers are one of the parties to the 14-year long conflict. An armed group who led the offensive that toppled Assad. The group started as an offshoot of Al Qaeda, went through many transformations over the years, and consolidated its hold over an enclave in the northwestern parts of Syria for the last several years. They come with a history and a big baggage of violations and oppressive practices. They say they have changed, that their aim is to build a country for all Syrians, a country of freedom, equality and justice. However, their practices and policies so far send mixed signals about the sincerity of those talks and the real intentions of those holding the main keys to power. Attempts to control the narrative and obscure parts of the story are evident and alarming. A national dialogue was hastily organized, poached in a half-day agenda and later celebrated as an achievement. Many senior officials from the Assad regime, some with proven criminal records, have been granted an amnesty and a seat at the table without any transparent due process.

Three months after the fall of the regime, government-aligned groups committed mass atrocities against religious minorities, killing thousands in the matter of days, without yet any signs of accountability. Almost six months after taking power, the new transitional government announced the formation of a transitional justice commission, whose mandate was limited to crimes committed by the Assad regime. Already, before officially starting its work, the commission has deprived victims of other actors from the right to justice.

As the saying goes, “history is written by victors”; and yes, victors, in the traditional sense, have the agency and power to write their version of history. In this story the real victors are us, the Syrian people; the men and women who endured through decades of fear, the victims of all tyrannies, the children who grew up with the sounds of war, the youth who spent their formative years in displacement or exile, and the voiceless who never got the chance to tell their stories.

I asked: who gets to write our history, and who gets to decide what goes into it? And here lies the answer: we should all have the right to contribute to this history, to share our memories, collections and thoughts. To build our personal, family, community, and national archives. To have the space to narrate our tales, and listen to those of others. We all have the right to resist a story written only by the force of weapons.

My generation grew up on a history that was mostly forged. We now have the responsibility of ensuring that the upcoming generation reads a history that’s more truthful. A history that’s not written in one single voice, nor dictated by those who’ve secured power. A story of plurality, richness and diversity.