Reclaiming the flow of time amid war

War unravels our sense of time. Hours stretch or collapse, and people find themselves between a past that feels out of reach and a future too uncertain to imagine. Drawing on numerous testimonies from Ukrainians since February 2022, as well as the author’s own experiences, this essay examines how people strive to reclaim time amid war – often through simple rituals that help anchor their lives.

I finally have a bit of time to think about time itself. It’s not that I never thought about it before. I’ve been interested in the notion of time – in how people perceive it in different circumstances – for ten years now. But there was always something more certain, more urgent, and more concrete that demanded my attention.

Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022 changed everything. It was the start of a new count of days. People experienced the passage of hours slowing down and speeding up, chronologies reshuffling, processes becoming un-synchronized, a rift between the past and the future, an inability to plan or fully experience the moment. Time stopped being an abstract concept. Now it was manifested clearly through the actions and inactions of people and institutions. The loss or excess of time could now be felt physically, and a new vocabulary for talking about time emerged.

In spring 2022, while working on a project documenting war experiences, I suggested my colleagues and I add a question about the perception of time to our interviews. This is a complicated subject and I’m still struck by the depth and the metaphorical nature of the answers we received. The pandemic, the full-scale war and, before that, the occupation of Crimea and the hybrid war in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, all started in winter and continued with a “lost spring”: these were instances of forced caesuras, pauses in a line of verse through which our view of time was refracted.

The routine passage of time doesn’t call attention to itself until it is undermined by an extraordinary event. For any given individual, this might be the birth of a child, the loss of a job, a forced move out of the country: sometimes these events are highly anticipated (like retirement or planned emigration); other times they are sudden and can be traumatizing. As for social groups, their collective chronology can be broken by extraordinary events large enough that they affect entire cities, countries, or continents. The pandemic was one such event, when many people began reconsidering their routines, trying to apportion time in a new way. Many of them experienced a loss of temporal guideposts, the inability to plan or remember – all of these stress reactions to broken routines and interrupted lives. This is commonly seen after trauma. While biological time unceasingly marches forward, social time – that which we share with others – breaks down.

With Russia's full-scale aggression, time ceased to function normally altogether. Over and over, the people whom my colleagues and I interviewed in the spring of 2022 spoke of “frozen time”, a “never-ending February 24”, and a “groundhog’s day” they couldn’t get away from. In April of that year, a woman from Kharkiv said, “It’s still as if I woke up in the morning to explosions – it’s still the 24th for me; that one moment is frozen.” A woman from Zaporizhzhia mentioned “the feeling that March never came. On the one hand, it seems like all this [war] has been going on for eternity. On the other, it’s like a single, drawn-out day, or maybe even night, and a dream you’ll wake up from to find none of it ever happened.” Here, the perception of time combines a state of stagnation with a sense of the unreality of the situation Ukrainians have found themselves in with the full-scale invasion.

This sense of “living in a dream” points to a departure from the bounds of ordinary routine. In a 2023 article about forced emigration from Russian-occupied Crimea, anthropologist Greta Uehling writes about the metaphors of dreams and nightmares that fill the stories people tell about traveling to and from the peninsula. For academics, these stories are markers of psychological distancing, as well as a rift between perceptions of space and time. People who abandon their homes due to war undergo a forced displacement that is temporal as well as spatial. But ordinary space-time changes even for people who remain in their communities. Even if their physical home remains unharmed, there is no way to truly go back to it, since it belongs to a specific time-flow that has been cut off by war.

The use of the frozen time metaphor attests to emotional shock, an inability to restore the connection between the subjective past and future. Drawing on literary scholar Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht’s idea about the ever-broadening present, I liken these experiences to a violently expanding present. This is the opposite of experiencing the moment deeply, in all its fullness. The anxious present swallows up the past and possible versions of the future, reminding us aggressively of the existential threat of the here and now.

Like others, I was able to emerge from this state through deliberate acts that structured social time and made it possible to feel its passage again. Really, what saved us were the things that you do with other people and for other people: reading a book to a child, cooking food for people fleeing war, weaving camouflage nets, attending first-aid classes. Each of these largely mundane activities took on new meaning in war.

I don't mean urgent tasks when the imperative to act predominates (“there’s no time to think about tomorrow”); the important activities were the ones whose end goals were at least slightly off in the future. It is this process of gradually anchoring oneself in the future that has partially renewed people’s sense of control and agency. Still, full control is impossible in war. As a young woman pointed out in January 2025, “Some parts of the day are often out of our control. For example, I have no control over how many hours I’m going to sleep on any given day.” Russia’s regular nighttime attacks on Ukrainian cities and villages have affected the amount of sleep people get and, consequently, how much they can do the next day.

In May 2022, a woman from Kyiv spoke of “time being chopped into little pieces”. This is yet another of the common metaphors where people experience time as discrete fragments and not a continuous sequence of comparable hours. Anthropologist Marc Augé writes about three figures or shapes of forgetting that are bound up with memory and the perception of time. The first concerns rejecting the present and recent past in order to return to the distant past, to some “golden age”. The second concerns the suspension of the present and a broken connection to the past and future. The third is a rebeginning in opposition to cyclical repetition, a radically new start. The first form of forgetting occurs in cases of denying the present, as in the phrases “impossible war” or “a war that couldn’t happen in the 21st century”. The fragmentation of time serves as an example of the second form, suspension. Rebeginning is embodied in the practice of measuring time by how many days have elapsed since February 24, 2022, which was particularly common in the first spring of the full-scale invasion: “The calendar no longer means anything. There are only days of the war.” Each of these examples is about a severance between the modes of the past, present, and future. Building bridges between them is an important part of reclaiming time.

Time in war simultaneously speeds up and slows down. The oversaturation of events leaves no space to digest them; the fear of missing something important forces people to constantly be tuned into sources of information; the hours spent in shelters overnight stretch on endlessly. Stress and fatigue exacerbate the feeling that these events are happening “in a fog:” they lack definition; they pile on top of each other; memories of them are blurred. Various timelines unfold in parallel: one aligns with our existence in a particular space; another is defined by events on the front or in other places where people we love are. Orientation in such a temporal plurality requires additional effort even under normal conditions, to say nothing of war.

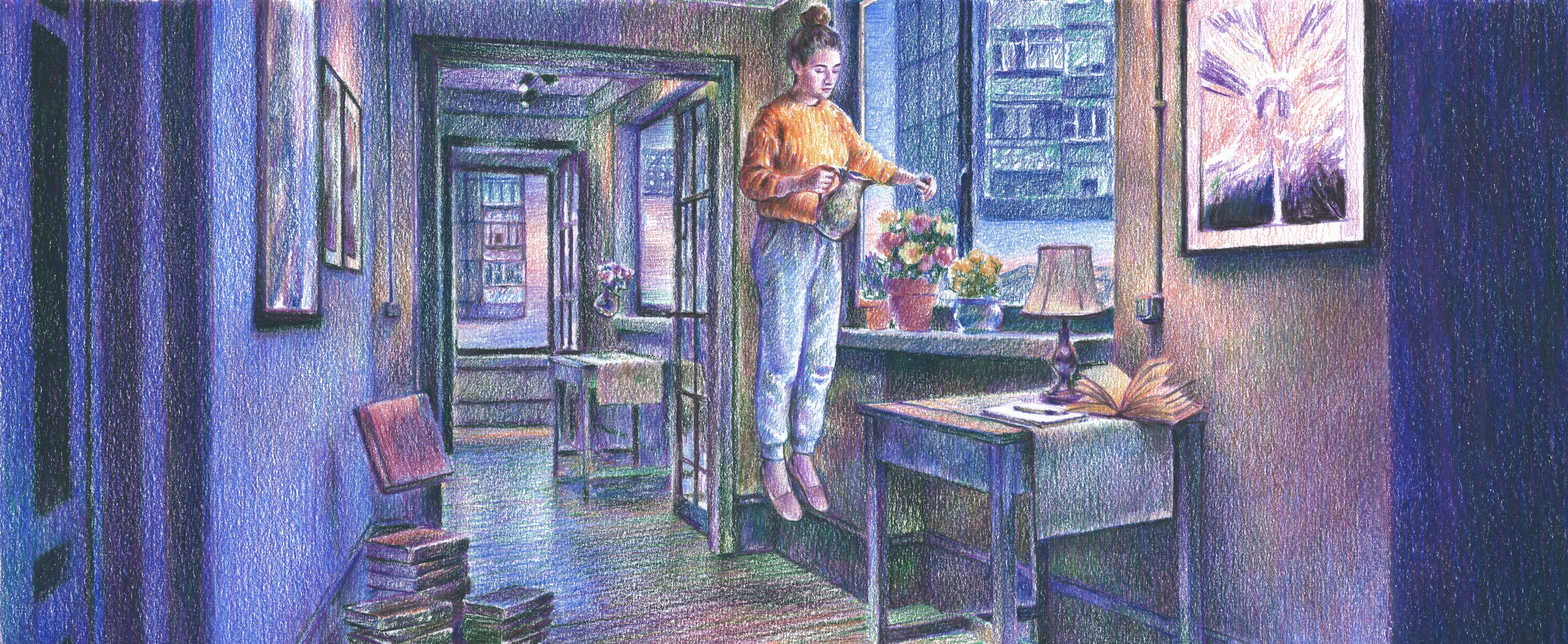

By 2024, the people we interviewed began reflecting on the partial renewal of timeflow, as they adapted to their new circumstances amid the full-scale invasion. At the same time, war can produce new ruptures, for example, in the wake of Russian attacks on the power grid or after the explosion of the Kakhovka dam. Each such event forces us to work out new reactive mechanisms, especially where perceptions of time are concerned. As during the pandemic, people have found several ways of recovering time in war. They’ve sought routines that could become new markers of time and create at least a minimal sense of control. Baking bread, taking care of houseplants or flower beds, even sharing a dinner together can help reclaim time. Still, these routines must be flexible enough to be shuffled when circumstances change.

Routines and rituals help synchronize us with other people, namely with those nearest us. Shared timelines are a mechanism for maintaining social ties; an awareness of what it means to be together. Sustained relationships with others help you escape the isolation of trauma.

I found the regular meetings my colleagues and I held in spring and summer 2022 to be very helpful. They reminded me that I wasn’t alone in my doubts and fears, and that I also had a professional identity that the war couldn’t take away. My Thursday nighttime shifts at the shelter for people who had fled frontline regions were my answer to my loss of a calendar: I didn’t remember dates, but I could at least keep the days of the week straight.

In addition to routines, it’s important to create events that transcend the everyday; whose meaning cannot be undermined by Russian aggression. This could entail looking to traditional, cyclical celebrations or creating new milestones for the memory to grab hold of. Celebrating Easter in wartime, as during the pandemic, serves to remind us of another calendar. Sacred time is cyclical, like the seasons or the movements of the planet: spring will come no matter what, and the sun will still shine in the morning.

War is full of emotionally charged events, so it helps to consciously slow down and reflect. When we step back and observe, we gain a perspective that is invisible to us in our standard wartime mode, where external dangers keep us in a state of constant movement. From an observational stance, we can seek meaning and gather together the pieces of our personal and collective histories. In his book The Burnout Society, philosopher Byung-Chul Han posits that people are suffering from a shortage of betweens and between-time, though it is there – and not in the constant stream of stimuli and reactions – that thinking happens.

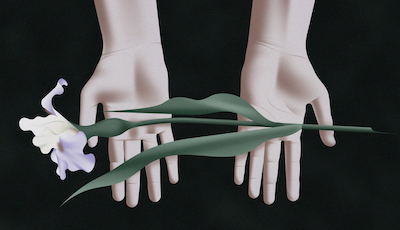

Finally, to reclaim time, we need to be able to operate within various planning horizons, namely the near and distant future. One resistance strategy is accepting that everything can change and simultaneously being able to see goals beyond simply surviving the present. The Ukrainian poet Iya Kiva uses the metaphor of a garden nurtured despite inevitable danger. Historian Orysia Kulick and filmmaker Maryna Stepanska have also talked about nurturing gardens, in re/visions. Plants become a metaphor for the connection between past and present, the cycle of rebirth, the humility with which we await the flowers and fruits of our efforts.

War radically narrows our sense of what is possible by undermining physical and mental health, ruining natural and human-made spaces, and contaminating water, air, and soil. Many hypothetical futures will never happen because the people who would have made them are gone. The sociologist Niklas Luhmann distinguishes future presents (what will actually happen tomorrow and beyond) and present futures (visions of the future that exist here and now). Ukrainian society has lost its future presents to war, but it still has its present futures. It is in these present futures that I see yet another dimension of resistance: we need to lay the groundwork today for a different tomorrow – one that is more humane, open, flexible, and stable. Futures are never empty: they are made of what we inherit from yesterday and create today. This space for radical imagination is to me a source of hope.

This article was written during a visiting scholarship at MacEwan University, in Canada. The author expresses her thanks to the Ukrainian Resource and Development Centre.

Translated from Ukrainian by Ali Kinsella

Copy-edited by Katharine Quinn-Judge

Illustration: Mitya Fenechkin