The future tense, or when land speaks through names

Roots can reside in the soil of birth, in the syllables of a name, or in a language carried across exile. This essay explores renamed places and endangered tongues, tracing how sovereignty is claimed, denied, or quietly preserved through words. It draws on encounters with poets, scholars and inherited memories. Moving from Crimea to Tibet, from Cree territories to Sami tundra and Uyghur regions, this text explores language as resistance against erasure, and as connection to land.

Languages die like rivers

Words wrapped around your tongue today

And broken to the shape of thought

Between your teeth and lips speaking

Now and today

Shall be faded hieroglyphics

Ten thousand years from now.

—Carl Sandburg

Where are my roots? Are they in a town where I was merely born but never lived in, a town whose name was polonized to Dobre Miasto (Good Town) literally from German Guttstadt, which is in fact a bad translation of its original Old Prussian Guddamistan, where gudde meant a bush or a thicket? Or are they in Myropil, in Zhytomyr Oblast in today’s Ukraine, where my great-grandmother and grandmother were born in the house of the Hutten-Czapski? Or is it in the castle of Kilravock in Scotland where my great great great grandfather was born? I recall the first scene of a Herzog movie where Aboriginal people sit on the ground against explosives, not letting anyone do harm to their land. Stubborn and persistent.

A Crimean Tatar scholar Nara Narimanova whom I spoke with carries out research on Crimean Tatar toponyms in Canada. As a kid, living then in Shahrisabz, in Uzbekistan, she was never told what Tatar she was, except that her homeland was Crimea. One day, when washing her hands before dinner, her father’s grandmother Feride, standing next to her, suddenly asked, “And you, what Tatar are you?” Nara thought about many Kazan’ Tatars among her colleagues at school, and so she answered she was a Kazan’ Tatar. “Never say that,” Feride replied, “because you're a Crimean Tatar. That's why we call our homeland Crimea.” This was a revelation for eight-year-old Nara.

Toponyms are love markers of original knowledge of people who had admired and depicted the land with words. Edmonton, where Nara lives now, used to be called ᐊᒥᐢᑿᒌᐚᐢᑲᐦᐃᑲᐣ amiskwacîwâskahikan in Cree language, meaning Beaver Hills House. I can immediately picture the place as a creek, a marsh channel, with pine trees honed perfectly until two sides of it would resemble an hourglass and one part fall down into the water. The beavers would meticulously place it across the creek to create a dam, i.e. a water tank. The water treasury protects forests against fires these days. The modern name was given by William Tomison coming originally from Edmonton north of London. He was a fur trader. Many native Cree people died of smallpox brought by colonizers. The Cree language was nearly lost due to their people fearing being treated as inferior or unable to secure a job.

“If names are not correct,” noted Confucius in Analects, “speech will not be in accordance with the truth of things.” The Chinese regime does the opposite on purpose. Tibetans established Tibet in the 7th century, a few centuries ahead of the Crimean Tatars. China annexed the region in 1950. In late 2023, it began using the Mandarin name “Xizang” for Tibet. The same name was used not that long ago by the British Museum and the French Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac museum as they exhibited Tibetan artefacts. After several weeks of protests by Tibetans, the museums erased the name “Xizang” and stuck to Tibet Autonomous Region only. Rectifying names is a way of holding power over another entity, as if packing them into a box. It is the same symbolic discourse of power measured so accurately by Pierre Bourdieu, a tax controller among sociologists inspecting power language.

Tibetans live in exile all over the world scattered in thirty different countries. I met writer Tsering Lama several years ago, when we stayed at the residency of the Jan Michalski foundation in Switzerland. Her family fled first to Nepal and later settled in Vancouver, Canada. I could experience her longing for a glimpse of mountains that would remind her of Tibet when we drove to a village north of Montreux. She could step out of the car and look at the mountain peaks with absolute admiration, which was enough for her to pursue her writing. Yet, she lost the Tibetan language. She grasps parts of words, but without understanding every single component one is unable to get even the gist of a word. She writes her books about Tibet in English. As does the poet Tsering Wangmo Dhompa, who originally comes from Nangchen, in eastern Tibet, and now lives in Philadelphia. She grew up in exile close to the community of elders and monks from her home place, and thus learned to speak Kham, her native dialect. But she cannot write in it. It has a special place in her body, like an organ one cannot live without. Her younger relatives speak Chinese more often, the language of work and business. She writes her books in English, which means Tibetans who don’t know the language cannot read them. It is like a wheel with a gap.

Tibetan poet Bhuchung D. Sonam lives in Dharmasala, in India, closely observed by China. He can still speak Tibetan with his family. His original home village, which he had to abandon when he was ten, is under Chinese occupation and there is no freedom to write or read in Tibetan. His father could read but not write, his mother is illiterate. In India, he is well-connected, yet Tibetans do not enjoy full rights there, they cannot own property, Indians are their landlords. Before, in Tibet, one could learn Tibetan in schools, but now, they are all colonized and under Chinese control. Bhuchung learnt English but he feels this language was imposed on him. He feels the necessity to tell his story. Who would listen to him and other Tibetan poets he translates to English, if they wrote only in Tibetan? “It is a curious fate to write for a people who is not one’s own and stranger still to write for the conquerors of one’s people,” comments the Aboriginal writer and scholar Mudrooroo Narogin, formerly Colin Johnson, in his book “Writing From the Fringe.” Again, the wheel is incomplete.

China also subjugated Uyghur lands and its peoples, who are hounded and oppressed. Uyghur poet Tahir Hamut Izgil now lives in Washington where he fled to with his family a few years ago, from what China calls the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, or Eastern Turkestan as it is known to Uyghurs. He grew up in Kashgar, a city which has been the possession of various dominions: the Mongol, Chinese, Tibetan, and Turkic, empires. Uyghurs are a predominantly Muslim, Turkic ethnicity who live in China’s north-western Xinjiang province. The Chinese regime has been relentlessly detaining over a million of Uyghurs and subjects many others to constant surveillance, religious restrictions, forced labor (and I am not naming all the harm done to Uyghurs by the Chinese). Tahir was arrested several years ago, while trying to travel to Turkey, where he wanted to study. Studying abroad, as it turned out, was forbidden for an Uyghur. He was detained and imprisoned for three years.

Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o was first imprisoned and later exiled for having chosen to write in his native language, Gikuyu. The quest for self-determination puts people at risk. Unable to define their fate in their home countries, both Tahir Hamut Izgil and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o were deprived of their sovereignty.

After Tahir’s release, he began everything from scratch and built a career in the film industry. And this is when things again got worse and he and his colleagues began being persecuted. Even though he is relatively safe now in the US, we talked cautiously. Tahir did not show up on the screen. I could only hear his voice. His interpreter from Uyghur to English, sitting next to me, has not allowed me to reveal their identity. I learned that, during previous Zoom conversations, unknown people would appear on the screen. The translator felt spied on.

Since his exile to the US, Tahir cannot speak to his parents nor brother who are still in Kashgar. Tahir told his story in his book “Waiting to Be Arrested at Night”, which he wrote in the Uyghur language, as he does not speak English fluently. He did not write it for the Uyghur people though. He wrote it for the outside world. If it weren’t for his translator Joshua L. Freeman, his message wouldn’t be heard today. Tahir’s second language is Chinese and even though he mastered it quite well, he would not be able to write poetry in this language. Still, Chinese was a gate to western literature that is not translated to Uyghur. He got access to American verses and prose via Chinese, while studying in Beijing. On his visits back to Kashgar he spoke to Chinese people in their language, but they would be angry at him, they would feel uneasy and insecure. They would rather him speak in Uyghur. As if a non-Uyghur had no right to speak to them in Chinese? Did they feel offended? Did they feel their language was being hijacked from them by someone from an ethnic minority?

With the Crimean Tatar poet I could not speak openly either. Because the poet lives in Crimea, we exchanged emails in Ukrainian. I wished I could grasp the personality of my interlocutor. I wish I knew the timbre of their voice, how they look. I wish I could look into their eyes. I know their poems though, in English translation, where the poet praises Crimea for its beauty. It is beauty I have to imagine through testimonies, photos, films. As if I were touching earth via glass.

What I can tell you is what the poet wrote to me in a veiled way so as not to endanger themselves. Their father was exiled to Uzbekistan as a child, while their mother was already born in exile. The family retained their language, but for the outside world and for general communication, radio and television, they had to adapt to Russian. At the beginning, there were no Crimean Tatar books in Uzbekistan. In 1957, a publishing house was established, named after an Uzbek poet, Gafur Gulyam, which would print books also in Crimean Tatar. Later, when they were allowed to return to Crimea, the poet’s family would order books in their language from Uzbekistan, as almost none could be found in their original homeland. Stalin’s henchmen had subserviently and fervently destroyed everything related to Tatar heritage. The poet studied three languages: Crimean Tatar, Ukrainian and Russian, and their literatures, and could write in all three of them, but consciously chose Crimean Tatar. Crimean Tatars are, in the poet’s words, in a “struggle for language”.

There exists a newspaper in the Crimean Tatar language that the poet and their mother used to subscribe to. It was convenient when it was published online. Later, it was published in paper but its future is now jeopardized. Suleiman Mamutov lives in Kyiv. His father is in Crimea and runs the newspaper. Not that long ago, the printing house which used to print the paper was advised by the Russian “Center Combating Extremism” (called by the locals the “Center E”) to stop this activity. The owners, even though they had known the editors of the paper for many years and were on good terms with them, had no other choice but to suspend the printing. They shared the letter they had received from the Center E with Suleiman’s father. It was an act of something real amongst all the harassment and false facades, even if painful. The newspaper is on the lookout for a new printing house.

Suleiman wishes to preserve his language. He teaches Crimean Tatar to his daughter. He could not rely on the Crimean Tatar school a few kilometers north of Kyiv, where it was taught only a few hours a week. He was also a volunteer fundraising for a project called the National Corpora of Crimean Tatar Language. It is an online database of texts in several languages. With the use of AI and trained models, two years later Crimean Tatar was incorporated into Google Translate. Still, if the outside world is devoid of a language, if that language does not live in cinemas, bars, courts, it becomes a home language, a private language only that cannot develop. It is very hard to preserve a language this way, as if one would like to keep palm trees in small pots on window sills at home. Or as if they were planted in the tundra, like Crimean Tatars exiled to distant lands. The word tundra comes originally from the Kildin Sámi language “tūndâr”, meaning a “treeless mountain tract”. The name adapted first to Russian, and later, in the 19th century to English. It spread, and is the sole word used for this particular ecosystem. Would we need the word if the tundra thawed as a result of climate change?

The etymology of Norway’s biggest northern city, Tromsø, is uncertain. Its Sami equivalent Romsa is a loan from Norwegian and most probably was a sacred mountain for the Sami. When I landed in Tromsø a few years ago, in mid-November, wearing my heaviest coat, ready for arctic frost, I was caught off-guard by spring-like plus fourteen degrees and had to strip myself to a mere thin sweater. Would we still need the sophisticated vocabulary the Sami use for snow? Apparently, during World War II, the Wehrmacht would wander around the Sami regions with a legendary list of Sami words for snow transcribed to German. I say legendary, just as the Sami poet Sigbjørn Skåden does. He shared the anecdote with me, and at first said he was sure he actually saw the list itself, but later remarked he’d only heard about it. The legend about the list circulated among the Sami. I was not able to trace the list. But the story is so vivid, so probable. Would anyone need such a list in fifty years? With the extinction of words or signifié as de Saussure wanted, its signifiants, the material objects would follow, and so those who named them too.

Many linguists refer to linguicide, a deliberate act of erasing a nation’s or people’s language. Language is not an abstract entity. Erasing a language means erasing people who speak it. The language can survive in its written form, but the speech dies. Or parole vanishes, while langue can endure, according to de Saussure’s nomenclature. Languages that die or were killed – meaning, the people who spoke them were annihilated – are more often related to as species, because they can become extinct. There are probably around 6800 languages on this planet. 4% of the earth’s population speaks 96 % of all languages. That is to say, a majority of languages is spoken by a minority of people. Some languages kill other languages or subjugate them, and their capital, in Bourdieu’s terms, is higher and thus more valuable. Each language is like a mirror of the minds of the people who speak it.

Behind the necklaces of sentences built of corals of phonemes and morphemes, there is a vast and particular archeology of lives, loves and disputes hidden. There is knowledge within a name. And those who have lived on a land know it intimately like the body of their lover. There is a legendary story of an American fighter plane that crashed at Bakers Creek in Australia during World War II. Four crew members survived. They were wandering around in search of help. Three of them died of starvation on the land of plenty. If only they had known all the names of the edible plants surrounding them, as the Aborigines do.

ariel would like to express his gratitude to his interlocutors and those who guided him, while working on this piece: Nara Narimanova, Mariia Shynkarenko, Vitaly Chernetsky, Sigbjørn Skåden, Olivia Lasky, Mamure Chabanova, Elina Novokhatska, Olesya Yaremchuk, Suleiman Mamutov, the Crimean Tatar poet who wished to remain anonymous, the translator from Uyghur to English who wished to remain anonymous, Tahir Hamut Izgil, Tsering Wangmo Dhompa, Bhuchung D. Sonam, Yuliya Yurchuk, Anastasia Levkova, Askold Melnyczuk. He is also grateful to Weiter Schreiben and Literarisches Colloquium Berlin, where he could work on the essay.

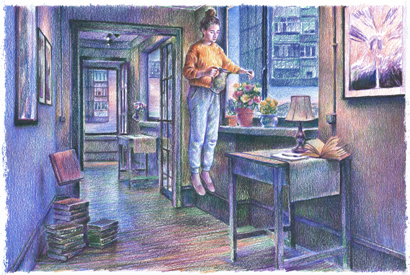

Illustration: Iryna Kostyshina