Women of Lviv: art that made a city

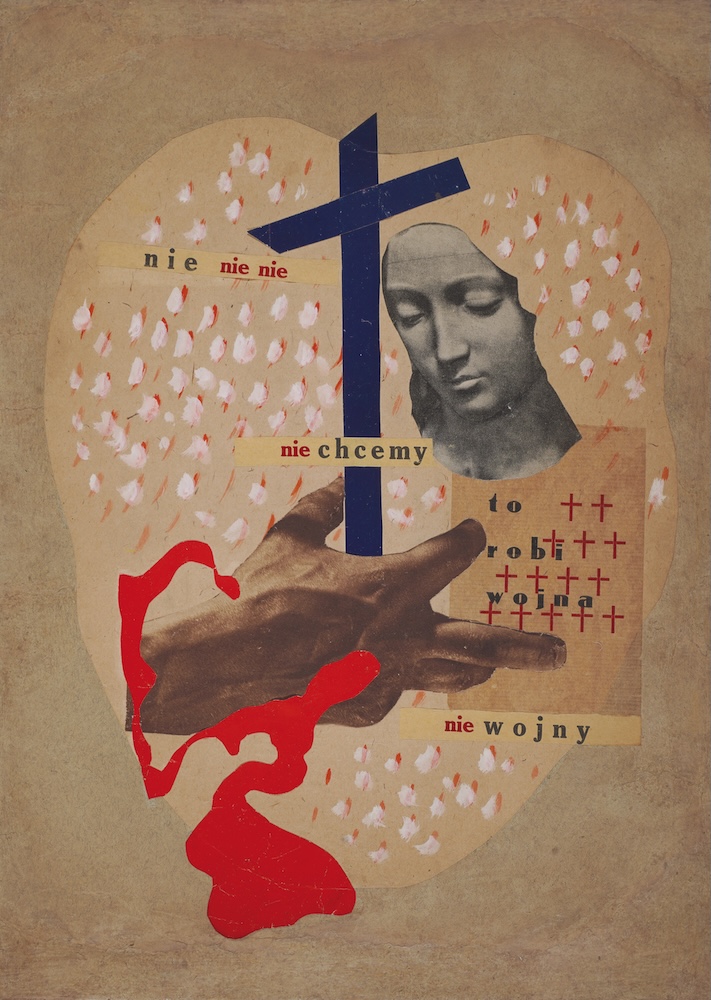

The Women of Lviv exhibition at the National Museum in Krakow displays artwork that, for the most part, has never before been shown outside of Ukraine. It presents the stories and works of 20th and 21st century women painters, photographers, writers, composers, and travelers, whose lives have all been closely tied to Lviv. Some names are well known, like Debora Vogel, a key figure of avant-garde circles. Others less so, such as Margit Reich-Sielska, whose striking collages from the 1930s include the piece We Do Not Want War. What emerges is the multifaceted identity of a city through women who shaped, questioned and endured it, through times of upheaval and war.

Women of Lviv [“Lwowianki / Львів’янки”], the exhibition curated by the Ukrainian-Estonian artist and researcher Andrij Bojarov, at the National Museum in Krakow, offers an intense and unique visual narrative. It chronicles the work of women artists against the backdrop of 20th and 21st century historical catastrophes. The two World Wars, the Holocaust, border changes, resettlements, persecutions, the current war against Ukraine, collective and individual traumas, death and loss, as well as resistance, resilience, and affirmations of life: all of this makes up the fabric of this small but essential exhibition.

The exhibition seeks to counter grand narratives, as well as national definitions of history, art and culture. Instead, it seeks to foreground notions of locality and specificity of place. In so doing, the curator has chosen to approach these women’s artistic practices and their biographical and historical experiences from the perspective of Lviv’s multiethnic, multilingual, and multireligious dimensions. He has thrown a light on dynamic processes of intertwining and disentangling, as well as the dramatic intersections of the identities and fates of Jews, Poles, and Ukrainians.

Composed of many of the female artists’ individual stories, the exhibition celebrates both autonomy and individuality and an impetus towards emancipation and freedom, steering us towards themes of multiplicity and difference. Yet ruptures and voids, death and destruction, intrude upon those narratives.

Both famous and forgotten women artists and thinkers from different periods of time and history are featured side by side in this exhibition space. To enumerate but a few, presented are: Wanda Diamand, Luna Amalia Drexler, Olia Gaidash, Sofia Jablonska, Olena Kulczycka, Józefa Kratochwila-Widymska, Alina Lan, Olha Marusyn, Janina Mierzecka, Jaroslava Muzyka, Margit Reich-Sielska, Janina Reichert-Toth, Erna Rosenstein, Stefania Turkewycz, Maria Wodzicka, Debora Vogel. In a transhistorical perspective, these women have been brought together by war, which, as Susan Sontag wrote, “rips, tears apart. […] eviscerates […] burns […] dismembers [and] ruins”.

All the women artists mentioned in the exhibition had close associations with Lviv by way of family, educational, and professional connections. All of their personal stories encompassed activism, self-development, altruism, co-creating an intellectual environment, and nurturing a multicultural legacy. These incredible stories, previously unknown or available only in snippets, have been collected and tenderly presented.

From texts in the exhibition space, we learn, for example, that the painter Jaroslava Muzyka (1894, Zaliztsi – died 1973, Lviv), was also a co-founder of the Association of Independent Ukrainian Artists (ANUM), and curated a collection of Jewish art donated to her by the painter Martin Kitz. In turn, the distinguished poet, writer, critic, and theorist, Debora Vogel (1900, Burshtyn – 1942, Lviv ghetto) not only inspired artistic circles, including Lviv Artes, but also created a discursive critical space for the works of avant-gardists. Likewise, the celebrated photographer, Wanda Diamand (1895, Weissenfeis – 1943, Warsaw) ran an artistic salon in Lviv in the 1920s and 1930s, and championed the work of artists, often supporting them financially. It was thanks to the sculptor Luna Amalia Drexler (1882, Lviv – 1933, Lviv) that the Polish Anthroposophical Society was founded, in 1917. Drexler was also a member of the city’s Council for Art. And in 1917, she co-founded the Association of Polish Women Artists (one of the first such women’s associations in this part of Europe). Among its members were the sculptor Janina Reichert-Toth (1895, Stary Sambir – 1986, Krakow), and the painters Maria Wodzicka (1878, Objezierze – 1966, Lviv) and Józefa Kratochwila-Widymska (1878, Lviv – 1965, Lviv).

One outstanding personality particularly highlighted in the exhibition is the artist Margit Reich-Sielska (1900, Kolomyia – 1980, Lviv), previously little known in Poland. The powerful message of her 1930s collage titled We Do Not Want War is given a prominent, central position. Reich-Sielska was born in Kolomyia to a Jewish family. Her father was an engineer. Educated in Lviv, and then in Krakow, Vienna and Paris (in the ateliers of Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant), Margit Reich-Sielska returned to Lviv in 1929 and co-founded the artistic group “artes”. She remained in Lviv throughout World War II, and after the border changes of 1945. The exhibition catalogue indicates that she hid under a false identity. Reich-Sielska’s work, which in so many ways defines and encapsulates the exhibition, uses collage to depict war not as a heroic event but as a sequence of death, despair, and destruction: a sea of corpses and graves, with a bloodstain spread across the map and taking almost the form of a heart). The collage can be seen as an accusation aimed at the future, and, at the same time, a cry of artistic protest against what unfolded in Europe in the 1930s.

Flanking the exhibition on the right side are works reflecting today’s Ukrainian cultural resistance to Russia’s criminal aggression against Ukraine. My-Musical (We-Musical) is a film created in 2022–2023 by a group of Ukrainian artists. The film depicts networks of mutual support, care, and self-help in a temporary accommodation shelter in Lviv for people fleeing war-torn areas. My-Musical is a work of self-reflection by those who’ve had to confront life-threatening situations, fear, loneliness, and loss. The musical itself is often filled with (dark) humor. The performers howl along to the sound of a missile alarm, sing a vista while preparing borsch, or engage in a choreographed duel based on self-defense techniques.

On the same screen, alongside the musical, a performance by artist Olha Marusyn according to the initial idea by Olia Gaidash describes sculptures looted from Ukrainian museums by the Russian army. An Abridged Catalog of Museum Objects Stolen from Ukrainian Museums During the Russian Invasion in 2022 corresponds perfectly with the activities of Jadwiga Reichert-Toth, who, after World War II, worked with her husband Fryderyk Toth to reassemble the Veit Stoss altarpiece, looted by the Nazis, recovered by the Polish government and transported in 1946 from Nuremberg to Krakow. Artworks that convey the experience of embodied history resonate in a particularly powerful way. Erna Rosenstein’s oil representations of her parents with severed heads (Dawn — Portrait of the Artist’s Father, 1979; Midnight — Portrait of the Artist’s Mother, 1979), painted from memory, point to the liminal historical event of the Holocaust, the traumatic memory of Jewish witnesses, the entanglement in violence and complicity of Polish bystanders in the Holocaust.

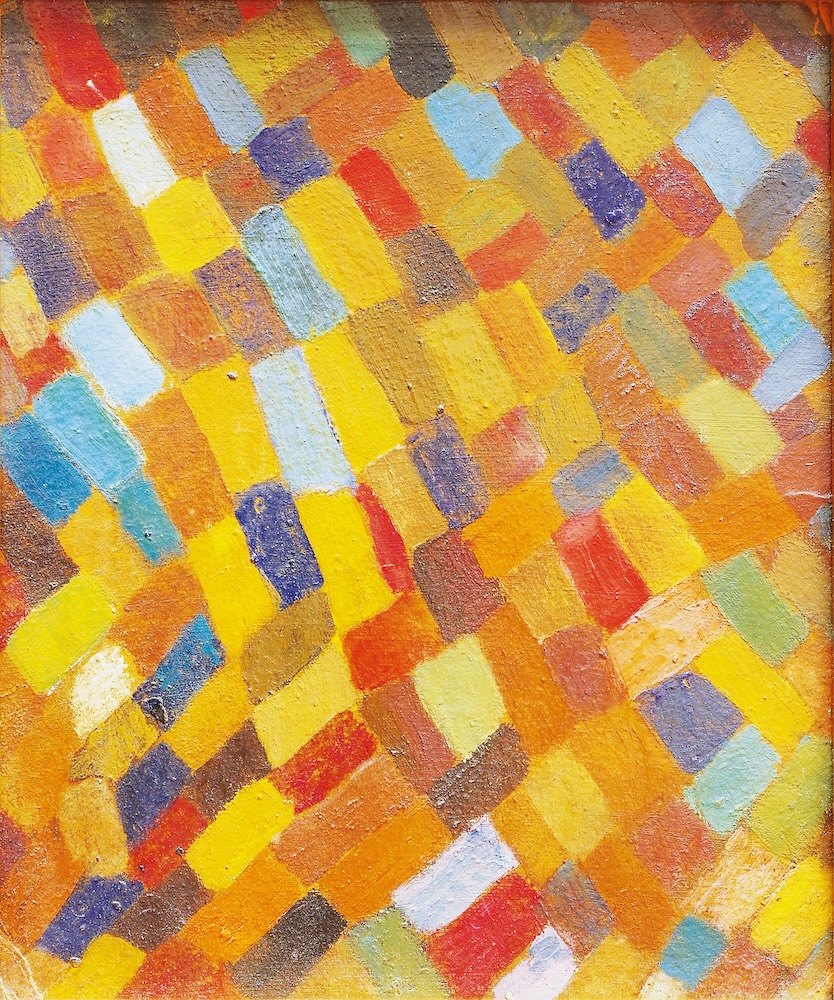

On the opposite, left side of the exhibition, are experiences that assert subjective autonomy, and the bold crossing of boundaries: geographical, political, cultural, existential, and social. Here we are presented with a journey towards independence, superbly documented in the photographs and films of the traveler Sofia Jablonska. Artists featured in this section are represented by one or two works, a short biography, and a photograph. Among the most renowned is Debora Vogel, recalled through an imaginative portrait created in 2023 by Vlodko Kostyrko. Among the less well known, or whose oeuvres have survived only in fragmentary form, is Olena Kulczycka. We see a facsimile of her 1915 etching, War Nightmares (On Justice), and her enamel-based Folk Art (1905-1906). There is also Luna Amalia Drexler, with her sculpture, Jolanta (Mulatto) (1910), and the artwork of the celebrated photographer Wanda Diamand, a friend of the artes-group circles. Particularly noteworthy is the only known work by Olga Blus-Lewicka (Leopold Lewicki’s mother) Untitled (Abstract Composition) from the 1930s – a small-scale, sensational abstraction, reminiscent of an ornamental tapestry or the bird’s-eye view of a rural landscape. Maria Wodzicka’s oil painting Concert (1932) depicts two women playing music in an interior opening onto a mysterious, almost ‘cosmic’ modernist cityscape. There is also Alina Lan (Paulina Landau), author of the book Halley’s Comet, illustrated by Jerzy Janisch and Aleksander Krzywobłocki; and Stefania Turkewycz with her excellent, expressionist musical compositions.

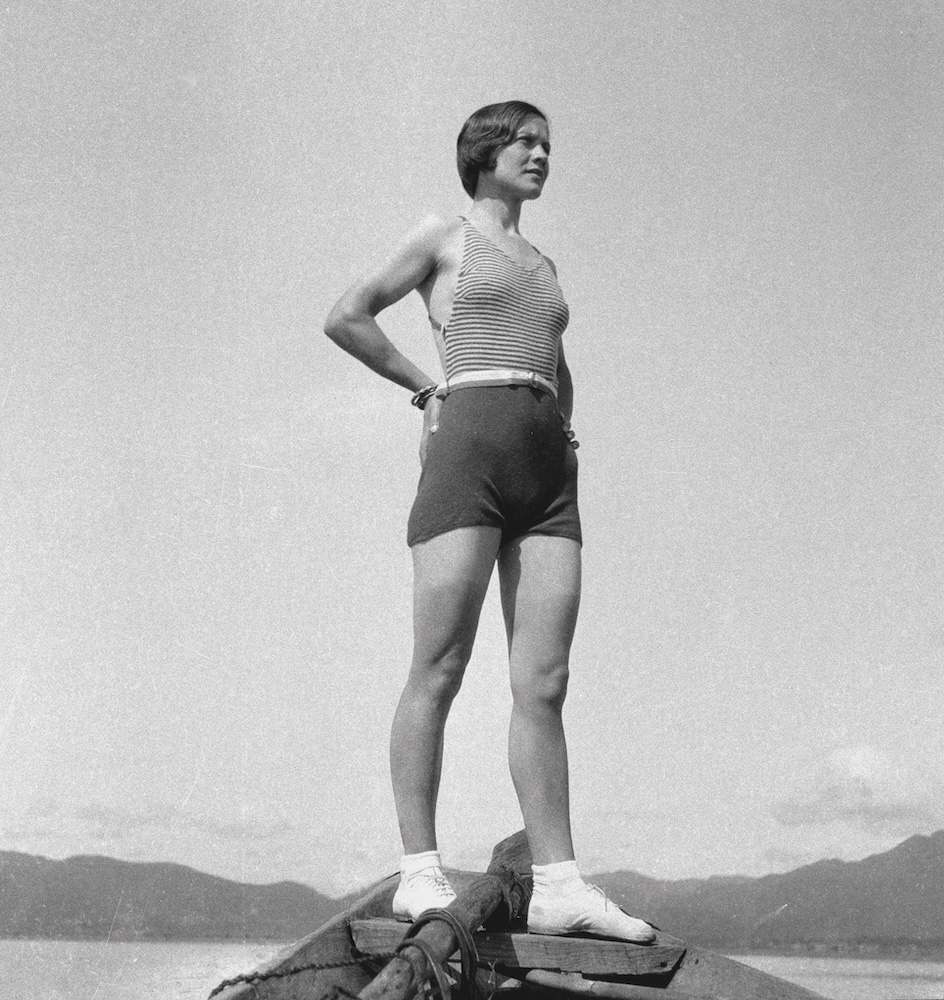

A major discovery presented in this section of the exhibition is the photographic and film work of Sofia Jablonska (1907, Hermanów – 1971, Paris). Curator offers a particularly sensitive selection and careful editing of her films, shot during her travels to Asian and Far East countries between 1933 and 1939. Jablonska was an avid traveler, photojournalist, writer, and suffragist. She was born near Lviv, the daughter of a Greek Catholic priest. She was full of energy, talent, imagination, courage, and perseverance. She pursued her early studies at a teachers’ college, at the State Academy of Commerce in Lviv, and later at a drama school attached to the Galician Musical Conservatory. She then left Lviv for Paris. In the 1920s she ran cinemas and a guesthouse. She also devoted herself to reportage. As a film reporter, she worked for Yunnan Fu, wrote books and articles (including for Lviv newspapers), and made films and photographs, lovingly capturing the cultural landscapes of Africa and Asia. With her family, she lived in various cities in Southeast Asia. After 1950 she resided in Paris. Eventually her peregrinations led her to the island of Noirmoutier on the Atlantic coast, her final place of residence. Her bold portraits and self-portraits, her notes about family life (including games and time spent with her young son), her keen records of everyday life and celebrations, and of breathtaking sites in Indonesia, Vietnam, Tahiti, Malaysia, and Cambodia in the 1930s, all of this emphasizes that the home of this woman of Lviv was in fact the entire world.

This outstanding exhibition is the first ever dedicated to the women artists who collectively created the Lviv cosmopolis. The vast majority of this artwork weaving a diverse and vibrant transhistorical community is shown for the first time outside of Ukraine. These artists studied at the best academies and universities, traveled throughout Europe, and in exceptional cases, to the far-flung corners of the globe. They were citizens of the world and, at the same time, local activists. Their work and artistic endeavors played a part in emancipatory transformations, shaped avant-garde trends, created a space for thought and action. For them, Lviv was a city of intense life, love, friendship, careers, growth and development, a place where some were forced to hide or to flee forever, a traumatic space filled with violence, horror and death; a temporary refuge, a starting point for a myriad of nomadic stories.

Translated from Polish by Barry Keane