The Polish economist Michał Kalecki (1899-1970), a father of the welfare state

Michał Kalecki developed a vision of economics that placed human welfare, employment, and social justice at its center. He had grown up in a Poland marked by poverty, inequality, and ethnic division. From these experiences grew a lifelong commitment to understanding, and transforming, the economic forces that determined people’s lives. He found international recognition, but later suffered from antisemitism and political repression in postwar communist Poland. His story is one of enduring faith in social justice.

Michał Kalecki’s bold economic vision came from a bitter reckoning with the 1930s Great Depression that turned Poland and other Central European countries into a vortex of poverty, ethnic tensions, and political radicalism. For most western historians and economists today, Kalecki remains a theorist whose critical insights helped lay the foundation for welfare-oriented capitalism in the second half of the 20th century. Yet he was also a thinker who imagined an alternative future for Europe: he believed nationalism could somehow be a progressive force, and that an ethnically inclusive nation-state could be achieved through economic solutions.

Kalecki’s ideas emerged from the specific context of interwar Poland. His thinking sought to create a viable future for people living in the shadow of Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union. He tried to show how to create jobs and secure food for all, Poles, Ukrainians, Jews, Germans, Belarusians, men and women, and young people – without resorting to mass emigration (as in the past), mass armament (as in Nazi Germany), or mass hunger (as in the Soviet Union). Kalecki was an engaged, politically minded scholar, who was no typical library man. He was a fierce opponent of capitalism who nevertheless had a business background; and the citizen of a young country that was falling apart in front of his eyes.

Michał Kalecki was born in 1899 in Łódź, in a family of Polonized Jewish entrepreneurs. His uncles and nephews owned businesses. In 1917 he moved to Warsaw to study at the Engineering College. After two semesters, however, he was drafted into the Telegraph Battalion and sent to Lwów, in the highly contested borderland of eastern Galicia. Between July and December 1919, Kalecki fought in the Polish-Ukrainian conflict that gripped the region. He saw mass starvation, death, and violence committed by marauding soldiers. His January 1920 military card shows a frail lance corporal. He was discharged, deemed “unfit for armed military service”.

Back in Warsaw, Kalecki threw himself into his scholarly work, but it was cut short by the illness and bankruptcy of his father, a former textile manufacturer in Łódź. He returned to Warsaw, where he rented a tiny room. He worked for a rating company and an economic journal, before securing a position at the Institute for Business Cycles and Prices, a governmental research institution. There, he quickly gained a reputation among Polish experts as “an autodidact with an extraordinary knowledge of economic reality and practical business affairs.”

Kalecki traced economic trends not just in Poland, but around the world. He warned of the far-reaching consequences of the October 1929 Wall Street crash. Yet the Polish government dismissed it as an ordinary market fluctuation. Kalecki’s immediate circle – Warsaw’s left-wing intelligentsia – watched as wages were cut and jobs evaporated.

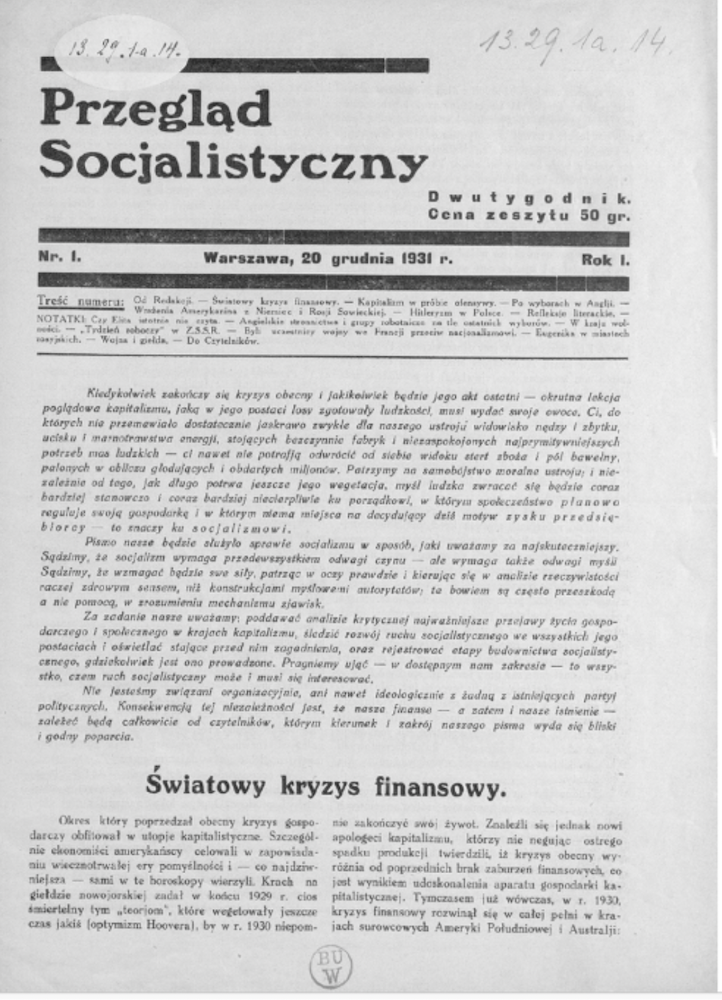

Kalecki had long been an Marxist who, while working in government administration, had to keep his political views to himself. But as fierce debates raged about Soviet communism and fascism Kalecki and his friends decided to come out as political radicals. In 1931, Kalecki co-founded the Socialist Review, a publication that launched him as a political writer. In the early 1930s, Polish heterodox socialism was less dogmatic than Soviet-style communism, but it did invest in the possibility of revolutionary change. It produced political essays, scholarly theories, econometric prose, and even party programs.

Kalecki’s social circle belonged to a second generation of the “Lviv-Warsaw School”, a neo-positivist group created at the end of the 19th century which echoed the Vienna Circle. In the pages of the Socialist Review, Kalecki focused on the rise of fascism, which he watched with anxiety.

In May 1932, German politics took a turn towards militarism. After Hitler secured 13.4 million votes in elections, Kalecki wrote about how Germany’s war economy might unfold: “One could expand the economy simply by plundering invaded lands, instead of buying raw materials on international markets.” Rearmament programs, he noted, were a form of public investment. Kalecki was convinced that a German war against Poland was bound to start, sooner or later. The question was how much time Germany needed for its military buildup. If the Nazis wen’t politically defeated, he warned, a grim future awaited. Politics would determine capitalism’s trajectory, not market mechanisms alone.

Kalecki developed a theory: higher wages, coupled with active non-military investments could stem recession and spur an economic rebound. For the first time, someone was demonstrating, in theoretical language, a direct relationship between capitalist investment and people’s spending, as well as between production and job creation (Kalecki called this “effective demand”). He pioneered a paradigm-shift for economics and policymaking. He showed an economy could grow not through armament efforts but through a combination of mass investments and consumption.

After the Socialist Review was closed for political reasons, Poland’s political climate deteriorated. The regime became openly autocratic. In 1934, Poland signed a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany, to secure its western border. A flood of Nazi propaganda bolstered Polish nationalists and their agenda of boycotting Jewish businesses and chasing Jews from Poland. The rise of ethnonationalism in Poland forced Kalecki to make an existential choice. Antisemitism was growing. The Institute of Business Cycles and Prices was labeled “a Judeo-communist cell.” By January 1936, Kalecki and his wife, Adela, emigrated to Stockholm.

In 1937, Kalecki’s two closest collaborators, Ludwik Landau and Marek Breit, drafted the Prosperity Program. This sixty-six-page document formulated full-employment policy as a strategy for Poland’s different national groups. It was initiated by the Polish Socialist party and the Jewish Labor Bund, together with Ukrainian, Belarusian and German socialists. This collaboration marked a pivotal moment in Polish socialists thinking about ethnic minority rights. The signature idea of a full-employment strategy was inspired by Kalecki’s innovations. The model implied that more investments and higher wages boosted consumption, while people’s spending conditioned the volume of the economy. Kalecki explained this mechanism in Essay on Theory in Business Cycles (1933), now a classic in political economy.

Moving beyond the capitalist business cycle was possible by having the state or planning institutions bolster investments and employment. The Prosperity Program extended Kalecki’s findings in the sphere of public policy and applied them to a planned socialist economy. The idea of full employment directly countered nationalist rhetoric calling for minority nationalities and supposedly “redundant” peasants, mostly Ukrainian, to be expelled out of Poland. “We seek to provide jobs for the unemployed in the cities and for an even higher number of the economically ‘superfluous’ people in the countryside,” the program declared. Poland’s living standards could rise without emigration and ethnic cleansing. Yet the program was ditched by the radical left fraction of the trade unions, shortly before war broke out.

By that time Kalecki had moved with his wife to the United Kingdom. He first worked in Cambridge and later at the Oxford Institute of Statistics. The institute studied Britain’s capacity to wage war against Hitler and prepared blueprints for transitioning from a war economy to peace. Isolated from the horrors of Nazi rule, Kalecki returned to the critiques of capitalism and fascism he had first raised in the Socialist Review in 1931-1932. As the British debated the terms of a postwar reconstruction, Kalecki’s most famous article, Political Aspects of Full Employment, appeared in 1943 in the journal Political Quarterly. There, Kalecki did not hide his belief that full employment was most achievable under socialism. But he also considered capitalist democracy as a home for a full-employment economy, provided it had a built-in institutional mechanism to curtail the power of big business, and kept market fluctuations in check.

Kalecki’s wartime articles were as much about the future of British politics as about a vision for a Europe and a world without fascism. During World War II, he became a prominent economist in Anglo-American circles. He sought to collaborate with like-minded experts – scholars dedicated to the political project of the welfare state beyond Soviet-style communism and integral nationalism. He tried to build political support for the idea of full-employment adjusted to underdeveloped countries. This thinking served as an important reference point for politicians and policymakers, from the creators of the British welfare state to Nehru in newly independent India. After ten years as chief economist at the United Nations secretariat in New York, Kalecki moved back to Poland in 1955, just in time to witness the “Thaw” and the end of Stalinism.

The Cold War was in full swing. The US rejected the notion of a full-employment economy as too left-wing; and Soviet authorities saw it as too bourgeois and Western. Kalecki tried to hold space for heterodox thinking in Communist Poland, and as an adviser to post-colonial countries. But he was well aware of how challenging it would be to translate his ideas into a global practice. He feared that the pitfalls of central planning, which he observed in Poland, could be repeated in the Third World.

Kalecki’s career drew to an end in a series of sudden events, as reflected in Communist party and secret police documents. In March 1968, student protests were met with beatings, arrests, and prison sentences. The Gomułka regime launched an overt campaign of antisemitism. Kalecki was targeted. His collaborators were fired, accused of “revisionism,” “formalism,” “ideologism”, and of “building bridges between the East and the West.”

In April 1970, Kalecki suffered a fatal stroke. Many of his students and collaborators were unable to attend his funeral: they had already been forced out of the country and stripped of Polish citizenship. The “travel document” they had been handed worked in one direction only.