Reading Albert Camus’s wartime Letters to a German Friend

The French 1957 Nobel laureate, Albert Camus, wrote his Letters to a German Friend in the midst of World War II. Addressing a fictional “German friend”, Camus dramatizes a rupture in a friendship once bound by shared ideals, but then broken by personal choices in the context of Nazism and war. We asked the Lithuanian philosopher Viktoras Bachmetjevas to explore how these letters illuminate Camus’s identity as a moralist, and their meaning for us today.

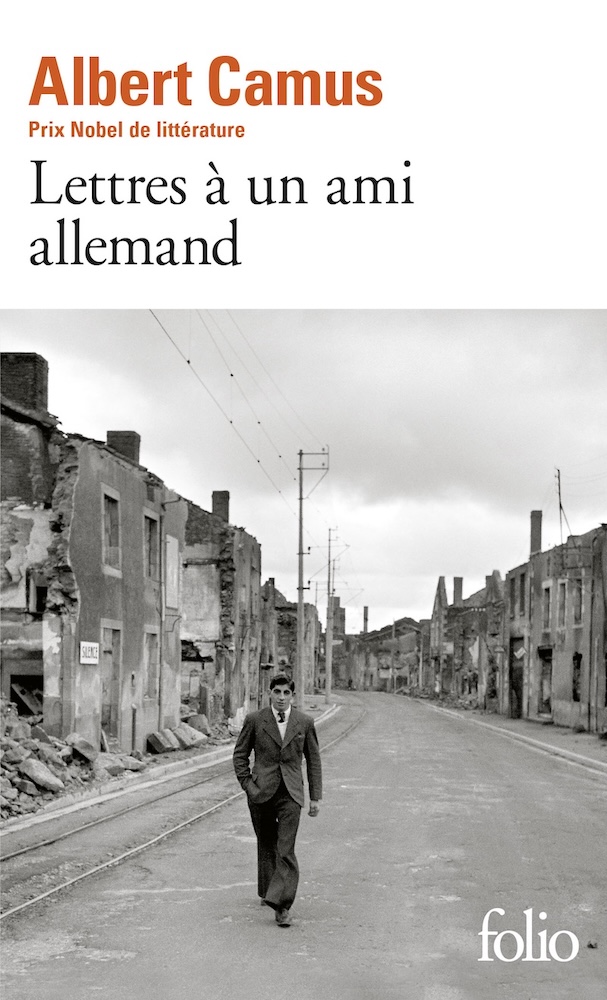

Nowhere is the spirit in which Camus envisaged moral principles more evident than in Letters to a German Friend, a series of texts he published during World War II.

“Moralist” has two senses in contemporary parlance. It might mean someone who believes that morality should have primacy over other things, like politics, commerce, or art. And, not excluding the first meaning, it might also mean someone who is given to moralizing, that is, who does not keep their morals to themselves. This moralist expects and even demands from others to adhere to his moral standards and principles, with all the negative overtones of didacticism that this second meaning might imply.

Albert Camus was a moralist in both senses. He belonged to a generation of French thinkers who believed that morality should guide politics. Camus committed to this ideal perhaps even more so than the thinkers, like Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, who (at least for a time) thought that Stalinist violence and terror were justified as means towards a more noble end of achieving communism. Camus rejected Stalinism outright – for him, humans cannot ever be reduced to mere pawns in the greater drama of history. But, together with Sartre and de Beauvoir, he believed that a moral individual should be involved in politics: morals have no sense if they are not applied in human reality. And there is no more appropriate place for applying morality than the realm where human interactions are played out, that is, politics.

That is not to say that the question of the relation between morality and politics is straightforward. One might recall Plato’s ideal of philosopher kings, which states that only the morally incorruptible are entitled to political power, or, on the other side of the spectrum, Niccolo Machiavelli’s markedly more pragmatic approach, in which the realities of the interplay of power become the guide for navigating political life. Immanuel Kant, trying to grasp the spectrum of possibilities, famously suggested a distinction between a political moralist and a moral politician. A political moralist, for Kant, is someone who values the ends over the principles. Perhaps inspired by Machiavelli, such a figure treats everything as a technical, tactical, localized problem. The principles are not eliminated in this case, but they are instrumental – adjusted according to the needs and circumstances of the day and applied, so to speak, retrospectively. The goal of the political moralist is power itself, while the guiding principle is whatever works.

By contrast, a moral politician is someone who incorporates moral principles as an integral part of his political activity. He is more interested in being morally just than in being effective. Jan Klabbers, drawing on this distinction, notes that Camus clearly is in the latter camp: in all his writings and, definitely, in all of his political activities and statements, Camus seems preoccupied primarily with the moral principles that guide one’s political action rather than the ensuing results. Arguably, this comes to the fore most powerfully in Letters to a German Friend.

His Letters are not about clever tactics, winning strategies, and pragmatics. They are about holding on to justice when the world and surrounding circumstances seemingly make it untenable, almost impossible. And it is in the fragile bond of friendship that he first tests this idea.

Friendship

For Aristotle, friendship is a conscious, intentional, and mutual benevolence: “To be friends, then, they must be mutually recognized as bearing goodwill and wishing well to each other.” He says that there can be three kinds of friendship: (a) friendship of utility, a sort of marriage of convenience, where each gets some benefit from the other, (b) friendship of pleasure, where each enjoys the other’s company, and (c) friendship of the good, where each loves the other for who they are. The first two kinds for Aristotle are incidental, unstable, and easily dissolved. Those who love because of utility love because of what is good for themselves, and those who love because of pleasure do so because of what is pleasant to themselves. Therefore, as circumstances change, these types of friendships end: “for if the one party is no longer pleasant or useful the other ceases to love him”. So a perfect friendship is the friendship of those “who wish well to their friends for their sake”. A friendship like that, Aristotle says, is possible only among those who are good in themselves and who are alike in virtue – they wish each other well not incidentally or according to circumstances, but “by reason of their own nature”.

While reading Camus’s letters to a German friend, it is hard to understand which of the Aristotelian friendships Camus has in mind. No doubt, it is not the friendship of those who are alike in virtue – if anything, Camus is spending a great deal of time articulating the difference between himself and his “friend”. But it does not seem that the friendship in question fits either of the two remaining kinds. Indeed, there is neither mutuality nor conscious, intentional benevolence. Camus’s tone seems more reproachful, accusatory, while the “German friend” remains voiceless, except for some reminisces from the past in the first letter that Camus reports, which also bear an accusatory character. One is tempted to ask: What kind of friendship is that? The hint is in the text: it is a friendship that is about to end. Camus makes that explicit himself: “I want to do for our friendship the only thing one can do for a friendship about to end – I want to make it explicit.” These words carry the pain of a farewell.

The “friendship” here is not really personal – it is a way for Camus to dramatize the moral gap between himself and those who chose conquest over justice. The friend here is no more, his presence noted only by his absence, a mere reminder of betrayal.

Elsewhere, when imagining the future, Camus soberly notes: “We shall meet soon again – if possible. But our friendship will be over.” In truth, perhaps the friendship is already over, but for one last bit of courtesy: “Today I am still close to you in spirit – your enemy, to be sure, but still a little your friend because I am withholding nothing from you here.” So it is a farewell letter to a friend who betrayed and, in this way, terminated the bond. Having seen how war can poison even the most intimate human bonds, Camus then turns to the larger stage: the meaning of greatness.

Greatness

The truth is that these are not letters in the strict sense – there is no question that Camus’s audience is not the Germans, but the French. Although he addresses the “Germans” directly, he clearly is writing for his compatriots, rather than the enemy, the former friend. The goal is motivational (as it so often is during the war): Camus needs, perhaps most of all for himself, to articulate the righteousness of his fight, to give himself a sense of direction and meaning. In 1943, at the moment of his first letter, this war is neither won nor lost, and seems eternal, impossible to win and inconceivable to lose. Perhaps that is why he is so keen after the war to stress that by “you” he really does not mean “Germans”, but “Nazis”, seemingly unaware that this throws the whole series of letters into a logical and moral conundrum. Should they really be read as letters to a Nazi friend? What would that even mean? One senses that Camus is not really concerned with his interlocutor at all. In the preface to the Italian edition, after the war, he writes: “I am contrasting two attitudes, not two nations, even if, at a certain moment in history, these two nations personified two enemy attitudes.”

The main distinction he finds between himself and the Germans is plain. For the German, the greatness of his country is the highest value: “Anything is good that contributes to its greatness.” In contrast, for Camus, this is unacceptable: “Greatness … is not the end in itself and not at any price.” Greatness is desirable, but conditional – it must be “borne out of regard for justice”. This is a crucial distinction, which Camus repeats in the Preface written after the war: “I love my country too much to be a nationalist.” By nationalist, he clearly means someone who thinks that his nation is above other nations and ascribes that to the German attitude. In contrast, his own attitude could perhaps best be described as that of a patriot, defined by the love of one’s country.

This determines further differences. German insistence on greatness at any price means war, pure and simple: greatness requires conquest. Camus’s attitude is contrary – he despises war, is suspicious of heroism, and does not believe violence has any positive content. But precisely for these reasons, his insistence on not giving in is a form of heroism – in overcoming oneself: “It is a great deal to face torture and death when you know for a fact that hatred and violence are empty things in themselves.”

War

It is almost a triviality to say that war changes everything, but the trivial aspect of the statement does not diminish its veracity and seriousness. War does indeed change everything. Nothing remains untouched; nothing evades the crushing totality, the pervasiveness of war – this is not simply a change of circumstances that affects our lives, like a change of seasons, or moods, or material conditions. The reality of war seems to encompass and reach so much more: there is no hiding place from the “circumstance” of war.

In the opening passages of his masterpiece, Totality and Infinity, Emmanuel Lévinas, himself a soldier and a prisoner of war, discusses the reality of war as this specific regime of being that no one can evade: “It establishes an order from which no one can keep his distance; nothing henceforth is exterior.” Perhaps the crucial insight here is that war not only uncovers the very harshness of reality as it is, but it also destroys the identity of the same; in other words, it changes who we are. The war affects us in ways that we do not notice immediately – we are substantially, not circumstantially, different while at war, during war, within it. Tetyana Ogarkova and Volodymyr Yermolenko, reflecting on the Ukrainian experience, describe it as life at the edge, but the edge here is rethought in regenerative terms: “The edge – what happens here changes everything. The edge is not the periphery of a centre, it is the centre. … The edge is where everything begins, not where it ends.”

War shifts traditional systems of reference, imbues them with new meaning. Perhaps sensing that, Camus feels the need to justify himself in the republication of the Letters after the war, as if a little embarrassed by the harshness of his words during the war: “They are topical writings and hence they may appear unjust.” Herein lies one of the many paradoxes of war: if, like Camus, one intends to fight not for the sake of mere victory, not for the sake of greatness only, but for victory and greatness that is achieved without compromising justice, the task is fulfilled with almost unbearable, self-contradictory tension.

Copy-edited by Larissa Babij.