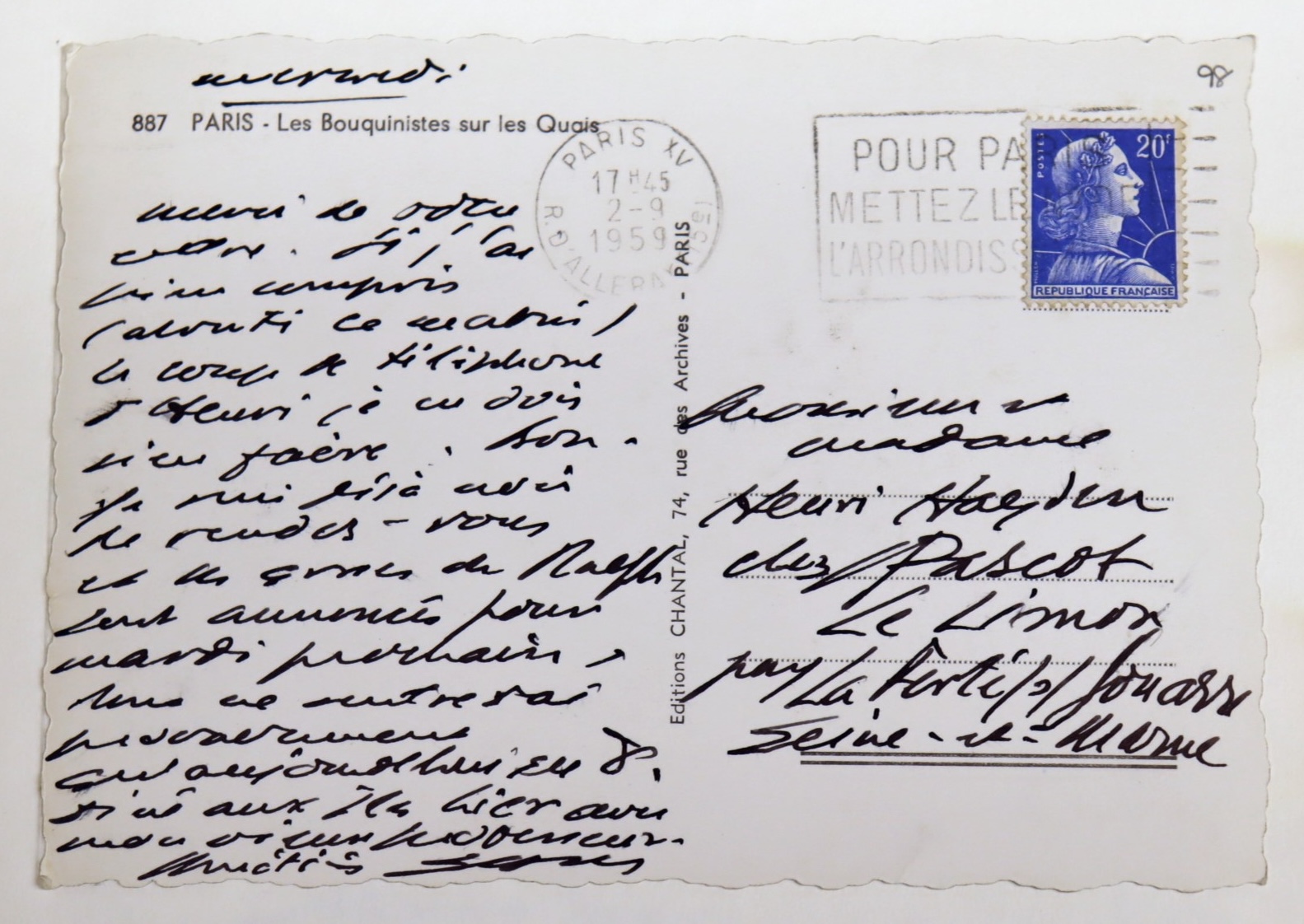

Samuel Beckett’s 1959 Paris postcard

Through the lens of a single, seemingly mundane postcard, this piece traces Samuel Beckett’s bond with the painter Henri Hayden, formed during their shared exile in a remote French village during World War II. The black-and-white image shows people browsing the bookstalls along the Seine river in Paris. The text on the postcard contains small talk and banal details, yet it is a lifeline between people who endured history’s chaos.

It was a friendship born of the accidents of war.

In October of 1942, Samuel Beckett and his partner Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil decided that it was time to leave Paris. The Gestapo had arrested his close friend in the Resistance, Alfred Péron. They fled south, sometimes on foot, ending up in the quiet village of Roussillon d’Apt, in the Vaucluse, near Avignon. The contrast with Paris could not have been more stark. Most of the homes in Roussillon in 1942 were still without running water, and life revolved around the rhythms of the farming year. Beckett soon found work on a farm with a family named the Audes, where one of his first tasks, in the thinning autumn days, was to dig through the muddy fields for potatoes left over from the harvest. Payment was usually in the form of wine or vegetables.

Life in the village was altered unexpectedly for Beckett and Suzanne one day when the local bus disgorged two new arrivals: the painter Henri Hayden and his wife Josette. Beckett’s biographer James Knowlson describes the moment in detail: “Josette climbed out of the bus itself, where she had been perched on some woman’s knees with, on her own knees, a cat in a basket; Henri extricated himself with some difficulty from a small trailer.” Henri Hayden was a Polish-born painter of Jewish descent. With his younger, vivacious wife, Josette, they had been part of the wider Parisian artistic world, and that in itself had been enough to make them appear suspicious to the Nazis. So, like Beckett and Suzanne, they had headed south, looking for somewhere remote enough to feel safe, and chance landed them in Rousillon.

The days changed for Beckett with the arrival of the Haydens. The initial bond came from a mutual interest in painting, and Beckett began to make a habit of stopping by to visit Henri and Josette, where they could talk about art. Before long, Beckett and Henri realized that they both enjoyed chess, and were closely enough matched in skill to make the games interesting. So, as the evenings lengthened over the winter of 1943, the two men passed into that phase of friendship in which it was possible to sit together for long periods of time without really saying much to one another, their companionship and the game sufficient in itself.

The friendship between these two couples, thrown together by the chaos of war, endured. Beckett’s subsequent letters of the late 1940s and early 1950s, such as those to the art critic Georges Duthuit (some of which he subsequently turned into his essay Three Dialogues) show him constantly referencing Hayden as a kind of aesthetic touchstone. “I am closed to questions of craftsmanship”, he tells Duthuit in 1949, making one exception: “it can produce such nice successes à la Hayden.” Meanwhile, Beckett plunged himself into the extraordinarily prolific period of writing that produced his trilogy of novels in French (Molloy and Malone Muert, both 1951, L'innommable, 1953), as well as En attendant Godot, first performed in 1953, Fin de partie, 1957, and Krapp’s Last Tape in 1958.

By the late 1950s, when Beckett was first beginning to experience the kind of international recognition that would lead to his Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969, what is most striking about the correspondence between Beckett and the Haydens is its often glorious banality. It is almost as if, just as the dull round of farmwork and silent games of chess in Roussillon had been a kind of refuge during the chaos of war, the sheer ordinariness of lives lived in quiet companionship was a kind of refuge for Beckett, as his own life became more uncontrollably public.

The postcard here, from the extensive collection of Beckett’s correspondence in the library of Trinity College, Dublin, is typical. The picture on the front – a black-and-white shot of two men browsing the bookstalls along the Seine, while the signature steeples of Notre Dame obligingly loom in the background – is so magnificently clichéd as to be almost transcendental. Other cards in the collection have the same quality of sublime over-determination; a view of the cliffs of Moher, in Ireland; an image of a windmill; an Air France plane in flight, from the days when complimentary postcards were something air travelers could expect in seat pockets. Each is extraordinary in its ordinariness.

Part of what confers the postcard with its compelling aura is that, unlike contemporary digital correspondence, it requires effort and planning. One has to choose an image and purchase the card, purchase a stamp, and then write and post it. To write something inconsequential on a postcard is to attest to the value of the inconsequential – a value that can only fully be realized, perhaps, by those whose lives have been overwhelmed by consequence.

In the case of this particular postcard, the inscription on the back is a kind of litany of the day-to-day. A possibly misunderstood phone call (“moronic this morning”); and then a recitation of unexceptional obligations, visits with family and friends. The “Ralph” referred to is almost certainly Ralph Cusack, an Irish painter who was married to Beckett’s cousin, Nancy Sinclair Beckett, and who had moved to the south of France; the couple had five children, two from Cusack’s first marriage. The “old professor” is probably H.O. White, who had nominated Beckett for the honorary doctorate that Trinity had bestowed on him a few months earlier.

It is in the recounting of such unremarkable details that we glimpse friendship as it renews itself from day to day in ordinary events. For a writer whose work constantly disavows sweeping visions or omniscient explanations, these little moments of simple connection between people thus acquire an unexpected poignancy – and hence the enduring power of Beckett’s postcards as testimonies to friendship.

Transcription:

[Paris] mercredi [cachet postal 2 septembre 1959]

Merci de votre lettre. Si j’ai bien compris (abruti ce matin) le coup de téléphone d'Henri, je ne dois rien faire. Bon. Je suis déjà noir de rendez-vous et les gosses de Ralph sont annoncés pour mardi prochain, donc ne rentrerai probablement qu’aujourd’hui en 8. Dîné aux Iles hier avec mon vieux professeur.

Amitiés

Sam

***

[Paris], Wednesday [postmark 2 September 1959]

Thanks for your letter. If I understood Henri’s telephone call properly (moronic this morning) I don’t need to do anything. Fine. I’m already fully booked with meetings and Ralph’s kids are supposed to be coming next Tuesday, so probably shan’t be back until a week today. Had dinner at the Iles with my old professor.

Best wishes

Sam

***

Acknowledgement is due to the Board of Trinity College Dublin. The author would like to thank Jane Maxwell and Laura Shanahan of the Library, Trinity College Dublin, for their assistance.