The beautiful day before yesterday: Derek Jarman’s cinema of saints and outcasts

Derek Jarman was a legendary and prolific British filmmaker, artist and activist, unwavering in his fight for both artistic freedom and human rights. His vision and stubborn resolve enabled him to cultivate a garden in the rocky soil of Dungeness, where he bought a house in the shadow of a nuclear power plant. Against all odds and in defiance of social expectations, Jarman tended not only to this physical garden but to the garden of his characters – outcasts, saints and misfits who transcend time, drifting through his filmography and inspiring those who seek figures beyond the confines of mainstream cinema.

The first time I saw a film by Derek Jarman was in 1993, at a retrospective of his feature films at the Molodist Film Festival. What struck me most was the range of themes and styles: explicit homoerotic scenes – which made a strong impression on the Ukrainian audience at the time – took their place alongside punk debauchery, bursts of violence, a concentrated aestheticism, pronounced melodrama, meticulously traced theatricality, and a deliberate chaos in plot construction.

It took me years to realize that Jarman was a British filmmaker through and through, and that what seemed like unevenness was actually a quaver in a despairing and exalted monologue.

The Scene

Michael Derek Elworthy Jarman was born in Northwood (back then, in Middlesex, England, now a part of Greater London), in 1942, in the family of Elizabeth Evelyn, a housewife, and Lancelot Elworthy Jarman, a Royal Air Force officer.

Jarman studied at the Slade School of Fine Art at University College London. In August 1969, he moved to Upper Ground, opposite Blackfriars Bridge, the first of a series of gentrified warehouses on the river Thames. In his own words, quoted by Tony Peake in Derek Jarman: A Biography, it was “an exhilarating change after seven years in cramped Georgian terrace houses and basements. [...] The warehouse allowed me to slip quietly away from the ‘scene’ which for five years had been the center of my life – and had now exhausted itself – and establish my own idiosyncratic mode of living.” In the 1970s, Jarman had a studio at Butler’s Wharf. He was outspoken about his homosexuality and fought for gay rights. In 1986, Jarman was diagnosed as HIV positive. His illness prompted him to move to Prospect Cottage in Kent, near the nuclear power station. He died in 1994 of an AIDS-related illness in London, aged 52.

His career started with stage design. He designed stage sets and costumes for the Royal Ballet in Jazz Calendar, a 1968 production by Frederick Ashton. His break in the film industry came as production designer for Ken Russell’s historical psychological horror-drama film The Devils (1971).

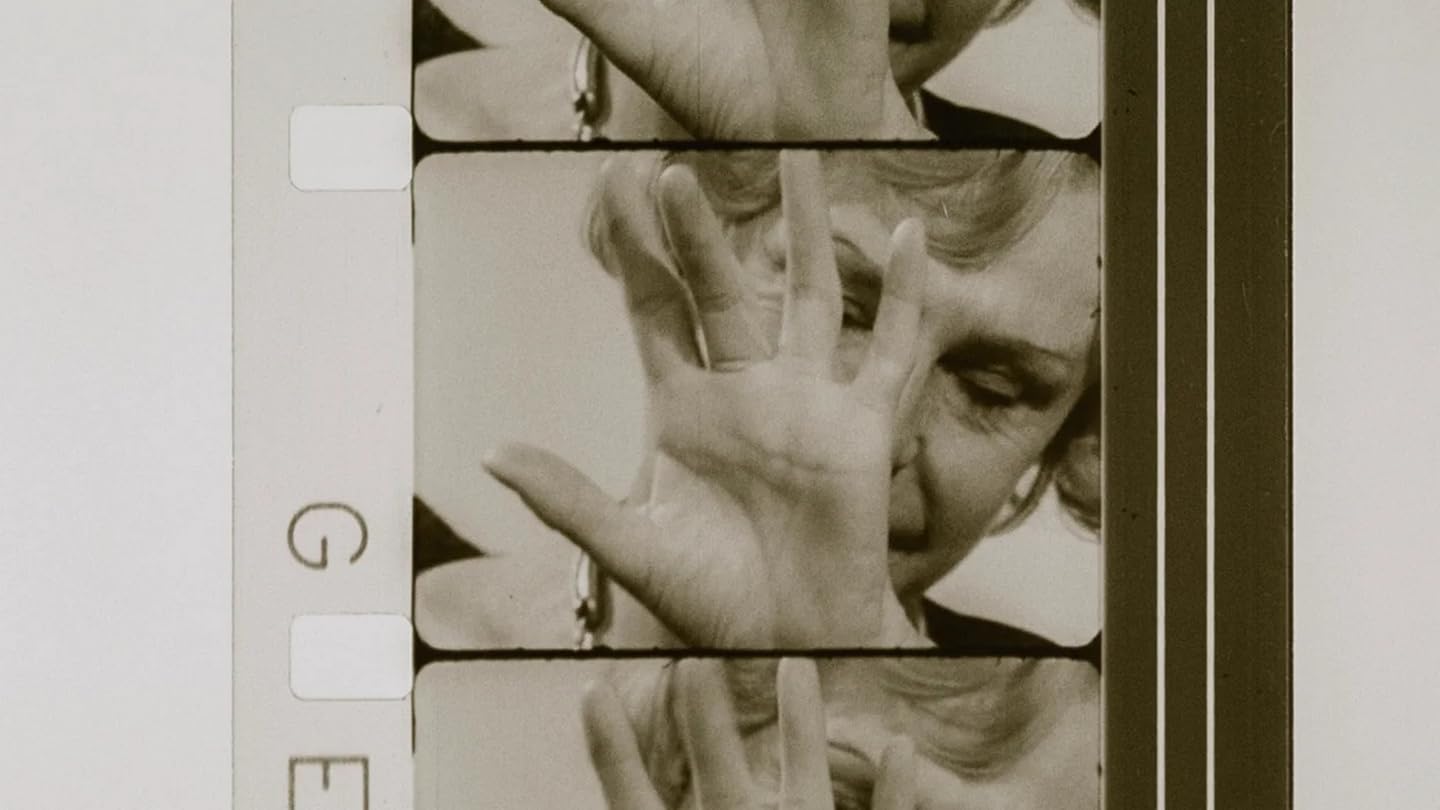

Jarman shot his first non-narrative short films on Super 8. In his early films, he peers into space, trying to glimpse the metaphysical underbelly of things. He does not care about time, for it holds too few secrets – and so plot doesn’t necessarily matter either. Sebastiane (1976) was his mainstream narrative debut. Over just under twenty years, he completed eleven feature films – right when British cinema, critics argued, was running out of breath. Jarman did not belong to the tradition of kitchen sink drama, a distinctly British version of film realism. Poverty, class divisions, parent-child conflicts, and coming-of-age stories are largely outside his focus. Jarman’s sense of injustice sprang from a different source.

In post-war Britain, the gay community was largely viewed as a problem, and gays faced criminal penalties and stigma. Jarman became aware of his homosexuality when he was sixteen, just as the Wolfenden Committee, chaired by educationalist Sir John Wolfenden, published its report. With the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, discrimination and prejudice grew with a vengeance. The new wave of homophobia peaked in 1988 with the passage of the notorious Section 28 in England, Scotland, and Wales, which banned the “promotion of homosexuality” in schools and local government institutions.

These very years saw Jarman at his creative prime, so film became a form of activism for him. Among his feature films, only The Tempest lacks explicit LGBT motifs, whereas The Last of England, The Garden, and Edward II all focus on the persecution and oppression of the gay community.

Martyrs

Sebastiane was the first British film with dialogue in Latin, and one of the earliest to portray homosexuality in a positive light. Jarman splits Saint Sebastian’s story into two distinct parts. The prologue depicts the luxury of Emperor Diocletian’s palace, a feast in honor of the Emperor’s favorite guardsman, Sebastian (Leonardo Treviglio), a sudden outburst of fury from the ruler, the murder of a Christian at court, and the protagonist’s exile to a remote province. It is here that the main plot unfolds, in a hot semi-desert along the sea coast, in a small garrison, among brutal legionaries commanded by the cruel centurion Severus (Barney James).

The ending is faithful to the canonical story. Yet the canon itself dates only to the 17th century: the myth of the young handsome man tied to a post and shot with arrows, stripped of his Renaissance masculinity for the sake of ecstatic gratification, was set down by Guido Reni. It is this image of Sebastiane that Jarman presents: taciturn, modest, irresistibly handsome, and stoically passive. Among his brutal comrades, he is the only one dancing. This exquisite “dance of the sun on the water” is the antithesis to the vulgar frolicking at Diocletian’s palace, where extras dance in a circle wearing giant prosthetic penises.

In both the palace and the desert, a distinctly gay gaze dominates: at Diocletian’s palace, it takes the form of over-the-top, gilded camp, while at the outpost it appears in explicit scenes and the contemplation of naked male bodies. Jarman introduces a heretical plotline: Severus falls in love with Sebastian and desires intimacy with him, but the demoted guardsman does not yield. Leonardo Treviglio’s character resists everyone’s obsession with sex because he is devoted to the highest form of love. God appears as an invisible Other, the unattainable apex of a love triangle. Heavenly love triumphs over even the most burning earthly passion. In this, Jarman is paradoxically religious.

Later his rhetoric changes drastically, but the martyrs remain.

Brothers-turned-lovers Sphinx and Angel, annihilated by ferocious policemen in Jubilee; the young couple in The Garden who endure Christ’s path of pain and humiliation, including the bearing of the cross; Edward, Gaveston, and Spencer, tortured to death in Edward II, – all of them die, just like Sebastian, because they don’t fit into a society obsessed with sex, homophobia, or both.

In his final film, Blue (1993), which consists of an unchanging, entirely blue frame and his own off-screen narration, Jarman himself becomes a martyr.

All those tortured to death by Babylon are granted eternal salvation on screen.

Bastards

Jarman belonged to the generation that still felt the aftershocks of World War II – that was horrified by the devastation of the world it had inherited, and hungry for answers.

Britain, however, skipped over the sixties. Its rock-‘n’-roll bands launched the British Invasion, but in terms of a counterculture driven by socio-political grievances, there was nothing comparable to the scene in 1960s America or to May 1968 in France. Everything happened a decade later, in a distinctly British way, following a formula: Dada begot the Lettrists, the Lettrists begot the Situationists, and the Situationists begot the punks.

A London Situationist, Malcolm McLaren, together with his supporters, staged a sit-in in his college in 1968. Yet his most successful provocation took place in 1975, when he founded the Sex Pistols. Punk music had existed for over a decade, but it was McLaren who gave rise to its subculture, borderline anarchist and aggressive. The Sex Pistols’ biggest hit, God Save the Queen, was a sacrilege of the national anthem.

Jarman understood this rebellion, even though he did not belong directly to the punk community. He directed a few music videos for punk and post-punk bands, the Sex Pistols included. Then there was his second feature film, Jubilee (1978), whose budget is noted with charming carelessness: either £50,000 or £200,000.

This madcap dystopian chronicle begins on a literary note. Queen Elizabeth I (Jenny Runacre), speaking in Shakespearean verse with her advisor, the occultist John Dee, accepts his suggestion to travel to the future, to the present day of Queen Elizabeth II. With the help of Ariel, the spirit guide from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Dee, the queen, and her lady-in-waiting find themselves in the shattered Britain of the 1970s. They move through a decaying London, where they are constantly forced to contend with the pranks of a group of punky nihilists. At some point, the infinitely cynical impresario Borgia Ginz (Orlando, real name Jack Birkett) enters the frame. He has purchased Westminster Cathedral and Buckingham Palace to transform them into musical venues. Absurdity and violence reign. Not everyone lives to the end.

The shoestring budget is evident at every turn. In the background, perfectly well-kept houses, streets, cars, and passersby appear from time to time. Jarman is not bothered by this. He constructs a situation in front of the camera, and that is enough for him. The finale takes place in a wholly artificial chronotope – Borgia’s nutty autocracy, where guards wear pseudo-Soviet uniforms and a senile Hitler blabbers about being “the greatest artist”.

The punks continually toss around phrases that they seem to have picked up at the Sorbonne of 1968: “Make your desires reality”; “When your desires become reality, you don’t need fantasy any longer, or art”; “Don’t dream it, be it.” The whole gang resembles the surrealist rebels of Goddard’s Weekend (1967), likewise zealously finishing off the remnants of civilization.

In Edward II, Edward (Steven Waddington) and his lover Piers Gaveston (Andrew Tiernan) are also misfits and provocateurs – not mere captives of “the love that dare not speak its name.” In a totally homophobic society, these two manifest themselves instead of hiding. They disturb the peace. It is for them that the new-wave star Annie Lennox sings Every Time We Say Goodbye.

Jarman portrays all these furious outcasts (for such was the old meaning of the word “punk”) with sympathy. He knows that for all their youthful fervor, the system will eventually swallow them up. Edward and Piers are killed, and the belligerent girls in Jubilee are bought by Borgia because in the postmodern (this word is scribbled on the wall in one of the first shots), an artist is no longer a genius on a pedestal, but a hired hand.

Dreamers

Four of Jarman’s features – The Angelic Conversation, The Last of England, War Requiem, and The Garden – have non-linear plots, echoing the approach of his early short films.

The rhythm of The Angelic Conversation (1985) is set by fragments of Shakespeare’s sonnets read by Judi Dench. The story consists primarily of homoerotic imagery and opaque landscapes through which two men travel. The director described the film as “a dream world, a world of magic and ritual, yet there are images there of the burning cars and radar systems, which remind you there is a price to be paid in order to gain this dream in the face of a world of violence.”

The Last of England takes its title from a painting by the Pre-Raphaelite painter Ford Madox Brown. It is a poetic and partly satirical meditation on the atmosphere of Thatcher’s England and its resurgent homophobia. The film contains executions, audio of a parliamentary session with Hitler’s voice spliced in, and a desperate embrace between a naked man and someone in a balaclava. One of the most famous scenes features Tilda Swinton as a bride mourning her executed husband.

The Garden (1990) recreates elements of the crucifixion. Christ is represented by a gay couple who are arrested, humiliated, tortured, and killed (Pontius Pilate is played by Orlando – who else?). There is a lot of religious iconography here: a Madonna (Tilda Swinton) harassed by paparazzi in balaclavas; a trans woman bullied by paparazzi and cisgender women; Jesus passively watching a hardened long-distance runner; a hanged Judas starring in a credit-card ad; twelve elderly women apostles seated at a table by the seaside. This all is accompanied by oddly tinted shots of beaches and urban slums and surreal alternations between electronic and classical music. And no dialogue. At the end, Jarman – by then HIV-positive – reads an elegy to the friends he has lost.

War Requiem (1989) is Jarman’s adaptation of Benjamin Britten’s choral and orchestral composition of the same name, which was itself based on the poetry of Wilfred Owen (Nathaniel Parker), a gay poet killed in the First World War at the age of 25. The story is told through the reminiscences of the Old Soldier (Laurence Olivier’s last appearance on screen), which are brought to life through documentary footage and acted scenes. The film lingers in the space between frontline truth and disturbing metaphor, in the limbo of the trench where Owen dies and is reborn again and again.

While their topics are very different, these films are extremely similar visually. There is the frenetic editing, the absence of a coherent plot, the shifts between black-and-white, color, and tinted images, the speed changes, fast-forwarding and rewinding, and anarchic poetics. These are stories where the stitches matter more than what they bind together. To Jarman, the present is a cacophony of neuroses. The 20th century is not a comfortable place for him.

Among Jarman’s feature films, The Tempest, Caravaggio, and Wittgenstein form a distinct group. None of their protagonists are martyrs to their faith like Sebastian, or doomed lovers like Edward and Gaveston. Their struggles are more broad-ranging; they hold magical power over people and things. Prospero is a sorcerer, lord of spirits. Caravaggio is a painter. Wittgenstein constructs a new concept of reality, using language as his lever. They all seem to belong to the universe of Brecht's epic theater, where time is not a constant. In the spirit of Brecht’s alienation effect, Jarman continually underscores the distance between characters and their circumstances. Shakespeare’s extravaganza ends with Prospero’s “our little life is rounded with a sleep”; Caravaggio’s evocative paintings appear in his reverie about a perfect lover; the afterword in Wittgenstein is about a boy who has dreamed up an ideal, never-seen-before world. All three are dreamers. All-powerful and infinitely lonely. Much like Jarman himself.

The beautiful day before yesterday

You have to hide in order to reveal. Masks – sometimes haphazardly formed out of paper bags – are a constant motif of Jarman’s, starting with his earliest works. The mask is a clear allegory for the condition of gay people forced to hide. But masks are also adjacent to mirrors. In Art of Mirrors, a short film Jarman made in 1973, masked protagonists pass around a shining mirror. A mirror flashes in Ariel’s hands in Jubilee. Yet these mirrors never reflect anyone or anything – only light, into the viewer’s eyes.

By juxtaposing the mirror with the camera lens, which absorbs light, Jarman draws the very boundaries of cinema.

Eventually, what started with a mirror ends with a blue screen. Blue (1993) is an existential manifesto rather than a political one. In his final film, Jarman becomes both protagonist and object. He at last finds the unity of images he has been looking for his whole life.

The lovers in The Last of England, The Garden, Jubilee, and Edward II are nearly indistinguishable: the same age, the same physical type, with similar haircuts, clothing, and movement styles. Paradoxically, this perfect sameness diminishes the erotic element of these films, instead elevating the themes of spiritual kinship, noble friendship, and even a certain mutual narcissism. Moreover, Jarman touches on the myth of the androgyne, but transcends the punishment of separation in pursuit of another eternal theme, an unattainable one – primal innocence. A return to Eden.

This makes him the opposite of Godard, who also tore through the surface of our being with his camera – and squeezed utopia into the screen. Jarman’s image of modernity is deeply uncomfortable. Even his most narrative-driven films are a dance of light on the smooth surface of the past. The beautiful day before yesterday. The day humanity keeps chasing.

Translated from Ukrainian by Hanna Leliv.

Copy-editing by Katharine Quinn-Judge.