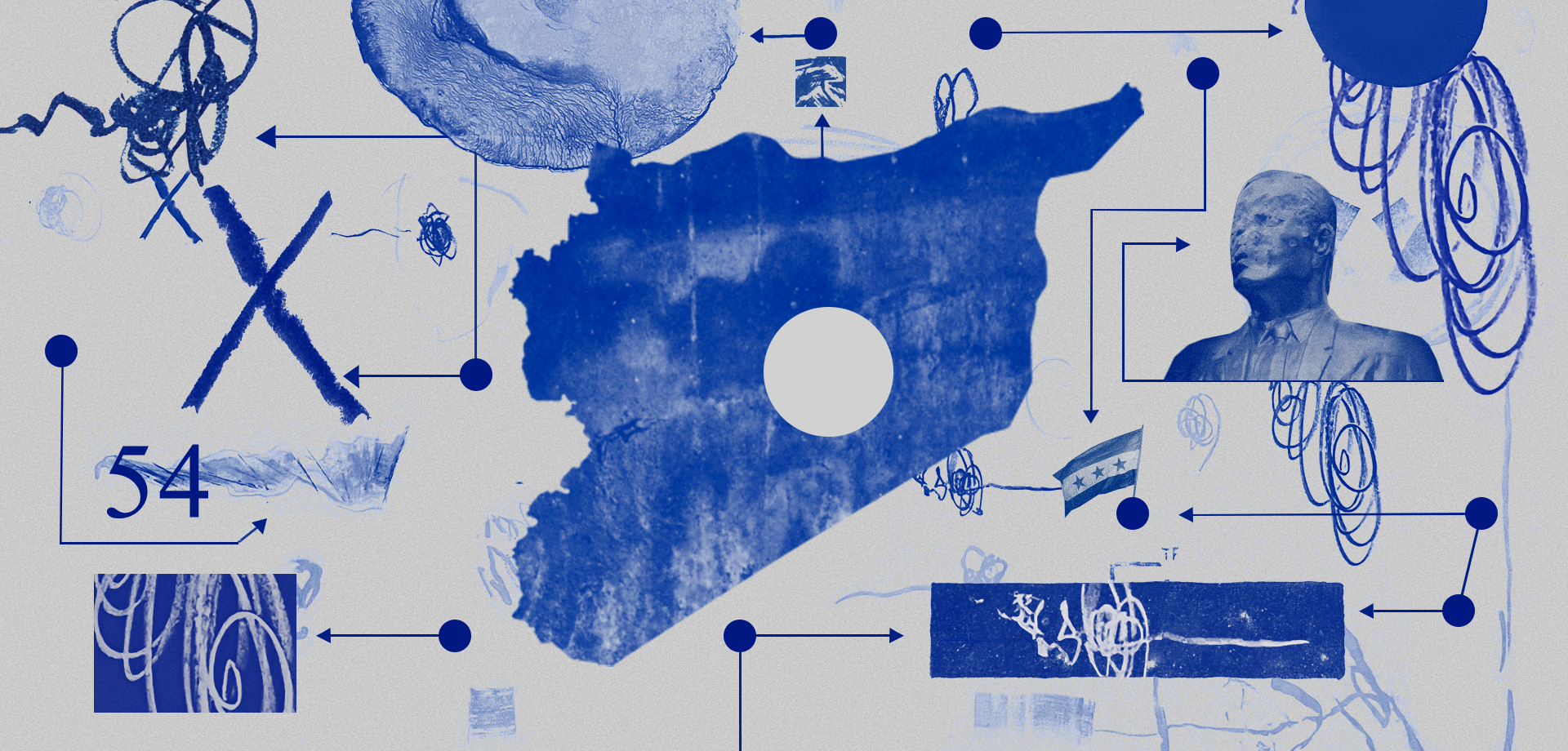

The Crimean Tatar Green Mosque, or Yeşil Cami, in 1924

This photo shows the 18th-century Green Mosque of Bakhchysarai, in Crimea, as it still stood just over a century ago. In 1924, the mosque’s collapse entered the diary of Usein Bodaninsky, a devoted guardian of Crimean Tatar heritage. His notes captured a cultural world that struggled to endure amid revolution, repression and erasure – not unlike the challenges Crimean Tatar tradition and memory face today under Russian occupation.

Yeşil Cami, or the “Green Mosque” in Crimean Tatar, was built in 1764 at the order of Dilara-bikeç, who was presumably the wife of the Crimean Khan, Qirim Geray, though her exact status remains uncertain. The construction date was inscribed inside the mosque. According to legend, before her death, Dilara expressed the wish to be buried in a spot where her favorite mosque would be visible. Indeed, from the windows of Yeşil Cami, there was a beautiful view of Bakhchysarai and, today, one can see Dilara-bikeç’s mausoleum, on the hillside opposite the mosque.

In 1924, Usein Bodaninsky, the founder and director of the Bakhchysarai museum, wrote in his diary, “On the eve of February 13, the entire northern wall of Yeşil Cami, the choir stalls, and the wooden frescoed ceiling, along with the northern slope of the roof, collapsed under the weight of a massive amount of thawed snow.” In these notes, Bodaninsky documented daily work at the museum. Yet he wrote about much more than the Khan’s palace: he embraced all the monuments of Bakhchysarai, the former capital of what was the Crimean Khanate, a Crimean Tatar state.

Bodaninsky is remembered in Crimean Tatar history as an artist, ethnographer, and founder of the Bakhchysarai palace museum. He was active in research, politics, and public life at a time when Crimea found itself at the epicenter of much political turmoil. The early 20th century was an extremely turbulent time for the peninsula. The February Revolution in the Russian Empire, which had annexed the Crimean Khanate, led to civil conflict and a division of the society into opposing factions.

Crimean Tatars decided to take the fate of their land into their own hands. November 1917 marked the first meeting of the Kurultai, the national assembly, which proclaimed the establishment of the Crimean People’s Republic. The Kurultai’s core members were from the National Party (Milli Firka), and Bodaninsky was among them. The democratic republic, headed by Noman Çelebicihan, was short-lived. In February 1918, the Bolsheviks seized power in Crimea and imposed new rules.

But the ideas voiced by the first Kurultai lived on. Some delegates sought ways to preserve Crimean Tatar culture and identity. Bodaninsky’s contribution to this cause is hard to overstate. Thanks to his initiative, on November 3, 1917, the Bakhchysarai palace museum was founded, doubling as a research center studying the history and ethnography of Crimean Tatars. Despite a complex political situation – the civil war swept over Crimea, and troops from the Ukrainian People’s Republic and its allies were entering Crimea – Bodaninsky worked tirelessly to preserve the museum. For a time, he was successful because creating and restoring cultural institutions was something aligned with the Bolshevik policy of korenizatsiya (Russian for “indigenization” or “nativization”). But in 1934 he was dismissed as director, and four years later, he was executed along with other Crimean Tatar intellectuals.

A hundred years have passed since Bodaninsky wrote his notes, and many of the buildings he described are gone. Some collapsed right before his eyes. That was the case with Yeşil Cami, the Green Mosque, whose history and decline were forever recorded in the Bakhchysarai museum’s diary.

According to Bodaninsky, Khan Qirim Geray, who had commissioned the mosque, was a well-educated, progressive ruler who made Bakhchysarai experience a brief but vibrant renaissance. With it came architectural monuments, calligraphy samples, poetry, and decorative art. One leading artist of the time was master Omer, a painter, architect, and calligrapher, whose name could be seen on the mosque’s main façade. He had supervised its construction.

Architecturally, the Green Mosque displayed a simple rectangular design. At its eastern corner, a minaret stood tall. By the time the records about the mosque appeared in the museum diary, it had already been partially ruined. The roof was covered with bright green tiles, which gave the mosque its name. The façade was decorated with pylons and two rows of windows. The frescos combined oriental motifs with European baroque influences of the 18th century. Inside, visitors could admire luxurious details: arcades with wooden columns, the carved parmaklık (grille) of the choir stalls, a mihrab (a niche in the wall indicating the direction of prayer for Muslims) with a stalactite pattern, frescoes in soft, pale rose shades, and calligraphy quotes from the Quran. The floor, paved with marble slabs, was covered with persian rugs, and a delicately crafted chandelier (“possibly Venetian glass,” Bodaninsky suggested) hanging from the ceiling.

The mosque met a difficult fate. Local elders recalled that it remained active until the mid-19th century, when a hurricane destroyed the upper part of the minaret. From then on, prayers were no longer performed, and the building fell into disrepair. Dervishes later settled in this place of worship, turning it into a tekija, a Dervish lodge. Only in the late 19th century did the Bakhchysarai philanthropist Aji Abdullah-efendi restore the building. After the roof was repaired and choir stalls added, a Crimean Tatar primary school opened in that space. Riza-efendi, who had been invited from the Ottoman empire, taught there.

In his diaries, Bodaninsky provided detailed accounts of his research on the mosque. On February 14, 1924, he and his colleagues photographed, measured, and studied the minaret. They found its stone base severely eroded by the wind and slightly leaning. Experts concluded that the building was dangerous. To prevent its collapse, urgent repairs were needed, or a dismantling altogether.

The very next day, Bodaninsky began copying the Green Mosque’s mural paintings. Students from the Bakhchysarai Tatar college of art and industry joined him. Thanks to their efforts, wooden elements were saved from looting. Part of the ceiling and the green glazed roof tiles were transported to the museum. The mosque remained in ruins for two more decades, and after World War II and the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, it was completely dismantled.

It is hard to imagine Bodaninsky’s feelings while the Green Mosque, ruined and looted, slowly disappeared from Crimea’s architectural map. A hundred years on, we can experience similar emotions as we contemplate the Khan’s palace, the world’s sole remaining example of Crimean Tatar palace architecture, being destroyed under the guise of “restoration.” What’s happening there now is a destruction of its authenticity. Ancient designs, paintings, and decorative elements are being replaced with contemporary materials, obliterating traces of true history.

A hundred years after Bodinsky wrote those notes, we are confronted with the issue of preserving not just individual buildings but what they represent: the continuity of cultural tradition, memory, and, most importantly, the presence of the Crimean Tatars in Crimea.

Translated from Ukrainian by Hanna Leliv